Because of an error in translation of the terms of a treaty between Spain and France signed in 1659, a hamlet in France on the border between the two countries is to this day Spanish. To enter Llivia motorists must make a detour into Spain and join another road, Route N20C, to cross back into France. Checkpoint police are Spanish, customs controls are tight, and shop prices are in pesetas, reports Gemini News Service.

By David Robie in Perpignan

Route N20C seems at first just like most other minor French country roads in the south. Narrow, bouncy and picturesque. But to drive along this short road one comes to a dead end in the tiny French hamlet of Llivia. Well, not quite . . . the Spanish village of Llivia.

This curious scrap of Spanish territory inside France is one of the strangest enclaves in the world.

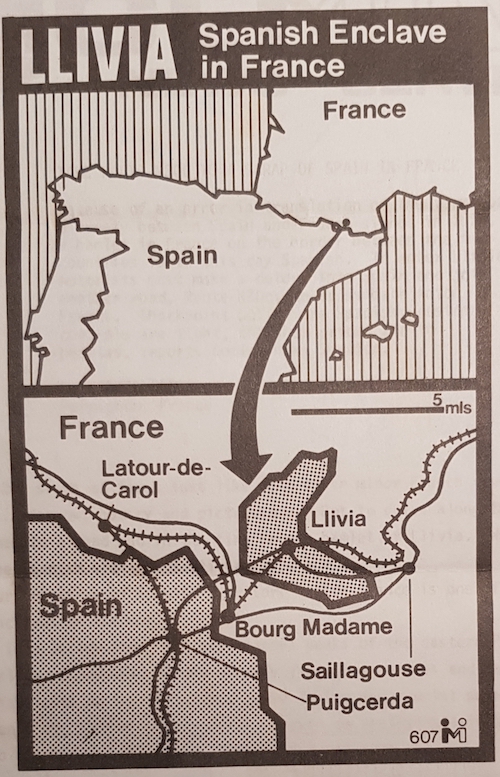

Tucked in a valley among the snow-capped peaks of the eastern Pyrenees near the principality of Andorra, Llivia is only five square miles (about 13 sq km) and has fewer than 900 inhabitants during the winter (more during the tourist season).

Few French and Spanish people I have spoken to realise Llivia exists. And most maps do not mention it, let alone pinpoint where it is.

Yet the enclave of Llivia has survived for more than three centuries — since the Peace of the Pyrenees Treaty of 1659 when Spain ceded to France the province of Rousillon and 33 villages of the Cedana valley in northern Catalonia. Llivia itself was then a “villa” and apparently remained Spanish because of an error in translation.

Today it is linked to Spain by the five mile (13 km) “neutral corridor” of Route N20C, which runs to Puigcerdà, just over the border in the Catalonian province of Gerona. Guardia civil (Spain’s paramilitary police), truck drivers and Llivia residents use this road freely.

French people used to have ready access to Llivia from nearby towns. But customs controls have been tightened up, barriers erected and the roads have “Prohibited entry without customs clearance” signs plastered everywhere.

To enter Llivia foreign motorists must now make a detour into Spain from the French border town of Bourg-Madame and join N20C at Puigcerdà. Crossing back into France the checkpoint police are in the olive-green of Spain — not French blue.

Customs regulations prohibit the import into Llivia of more than six pounds (2.7 kilos) of fruit, one pound of canned or bottled goods and three pints of wine. And no alcohol or cigarettes.

The village is a sleepy huddle of stone-walled cottages with slate roofs. Washing is hung out to dry and blankets to air on wrought iron balconies. Dominating everything is the tower — claimed to be the oldest pharmacy in Europe — around which a fortified church was built in the 15th century.

There is a modern hotel at the entrance to the village — alongside the red royal Castllian emblem of a yoked bunch of arrows which lets one know that this is Spain. Several modern houses front the main street.

Placards above the little stores and cafes are in Spanish and the prices are in pesetas but francs will do if one does not mind paying a steep loading.

One of the largest buildings in town is a four-storey, white-washed and wooden-shuttered police station with a sign above the main door saying Todo por la Patria — “everything for the motherland”. It looks big enough to hold a small garrison but the Pyrenees Treaty permits Spain to have six soldiers or guardia civil in the enclave at one time.

“In fact,” an employee at the ayutamiento (town hall) confided in me, “there are eight at the moment.” But, she added, this was not the first time the treaty had been infringed.

During the Spanish Civil War refugee republican soldiers sheltered in Llivia by the score. At first, the French authorities turned a blind eye to them, but their number swelled so much that they became an embarrassment.

Today Spain seems to be content with the Pyrenees Treaty and France lives with Llivia. Suggestions by France in the last couple of decades that Spain cede Llivia in return for more limited powers for the the French co-principality of Andorra have quietly faded away.

David Robie is a New Zealand journalist. He has been a reporter and subeditor of the Melbourne Herald; chief subeditor then editor of the Sunday Observer, Melbourne; chief subeditor then acting night editor of the Rand Daily Mail, Johannesburg, South Africa; and group features editor of the Daily Nation, Nairobi, Kenya. He is now an editor with Agence France-Presse in Paris and a correspondent for Gemini News Service.