REVIEWS: David Robie, editor of Pacific Journalism Review

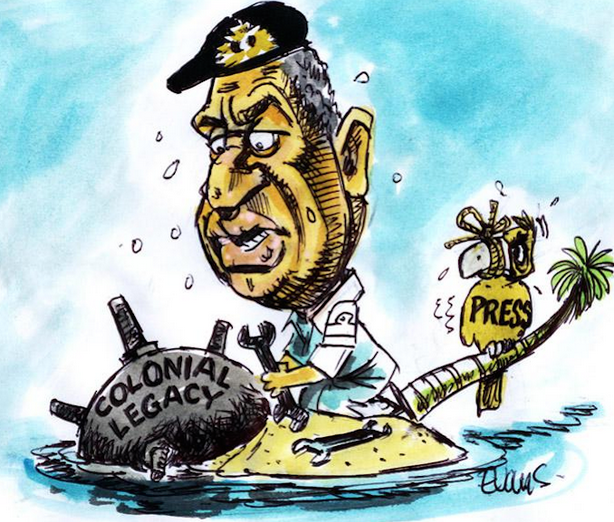

When Commodore (now rear admiral retired and an elected prime minister) Voreqe Bainimarama staged Fiji’s fourth “coup to end all coups” on 5 December 2006, it was widely misunderstood, misinterpreted and misrepresented by a legion of politicians, foreign affairs officials, journalists and even some historians.

A chorus of voices continually argued for the restoration of “democracy” – not only the flawed version of democracy that had persisted in various forms since independence from colonial Britain in 1970, but specifically the arguably illegal and unconstitutional government of merchant banker Laisenia Qarase that had been installed on the coattails of the third (attempted) coup in 2000.

Yet in spite of superficial appearances, Bainimarama’s 2006 coup contrasted sharply with its predecessors.

Bainimarama attempted to dodge the mistakes made by Sitiveni Rabuka after he carried out both of Fiji’s first two coups in 1987 while retaining the structures of power.

Instead, notes New Zealand historian Robbie Robertson who lived in Fiji for many years, Bainimarama “began to transform elements of Fiji: Taukei deference to tradition, the provision of golden eggs to sustain the old [chiefly] elite, the power enjoyed by the media and judiciary, rural neglect and infrastructural inertia” (p. 314). But that wasn’t all.

[H]e brazenly navigated international hostility to his illegal regime. Then, having accepted an independent process for developing a new constitution, he rejected its outcome, fearing it threatened his hold on power and would restore much of what he had undone. (Ibid.)

Bainimarama reset electoral rules, abolished communalism in order to pull the rug from under the old chiefly elite, and provided the first non-communal foundation for voting in Fiji.

Landslide victory

Landslide victory

Then he was voted in as legal prime minister of Fiji with an overwhelming personal majority and a landslide victory for his fledgling FijiFirst Party in September 2014. He left his critics in Australia and New Zealand floundering in his wake.

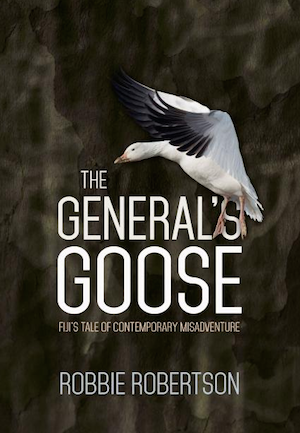

Robertson is well-qualified to write this well-timed book, The General’s Goose: Fiji’s Tale of Contemporary Misadventure, with Bainimarama due to be tested again this year with another election. He is a former history lecturer at the Suva-based regional University of the South Pacific at the time of Rabuka’s original coups (when I first met him).

He and his journalist wife Akosita Tamanisau wrote a definitive account of the 1987 events and the ousting of Dr Timoci Bavadra’s visionary and multiracial Fiji Labour Party-led government, Fiji: Shattered Coups (1988), ultimately leading to his expulsion from Fiji by the Rabuka regime. He also followed this up with Government by the Gun (2001) on the 2000 coup, and other titles.

Robertson later returned to Fiji as professor of Development Studies at USP and he has also been professor and head of Arts and Social Sciences at James Cook University in Townsville, Queensland, as well as holding posts at La Trobe University, the Australian National University and the University of Otago.

He has published widely on globalisation. He is thus able to bring a unique perspective on Fiji over three decades and is currently professor and dean of Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities at Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne.

Since 2006, Fiji has slipped steadily away from Australian and New Zealand influence, as outlined by Robertson. However, this is a state of affairs blamed by Bainimarama on Canberra and Wellington for their failed and blind policies.

Ever since the 2014 election, Bainimarama has maintained a “hardline” on the Pacific’s political architecture through his Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF) alternative to the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), and on the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER) Plus trade deal.

‘Turned their backs’

While in Brisbane for an international conference in 2015, Bainimarama took the opportunity to remind his audience that Australia and New Zealand “as traditional friends had turned their backs on Fiji”. He added:

How much sooner we might have been able to return Fiji to parliamentary rule if we hadn’t expended so much effort on simply surviving … defending the status quo in Fiji was indefensible, intellectually and morally (p. 294).

For the first time in Fiji’s history, Bainimarama steered the country closer to a “standard model of liberal democracy” and away from the British colonial and race-based legacy.

“Government still remained the familiar goose,” writes Robertson, “but this time, its golden eggs were distributed more evenly than before”. The author attributes this to “bypassing chiefly hands” for tribal land lease monies, through welfare and educational programmes no longer race-bound, and through bold rural public road, water and electrification projects.

Admittedly, argues Robertson, like Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara (Fiji’s prime minister at independence and later president), Rabuka and Qarase, “Bainimarama had cronies and the military continues to benefit excessively from his ascendancy”. Nevertheless, Bainimarama’s “outstanding controversial achievement remains undoubtedly his rebooting of Fiji’s operating system in 2013”.

Robertson’s scholarship is meticulous and drawn from an impressive range of sources, including his own work over more than three decades. One of the features of his latest book are his analysis of former British SAS Warrant Officer Lisoni Ligairi and the role of the First Meridian Squadron (renamed in 1999 from the “coup proof” Counter Revolutionary Warfare Unit – CRWU), and the “public face” of Coup 3, businessman George Speight, now serving a life sentence in prison for treason.

His reflections on and interpretations of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces Board of Inquiry (known as BoI) into the May 2000 coup are also extremely valuable. Much of this has never before been available in an annotated and tested published form, although it is available as full transcripts on the “Truth for Fiji” website.

‘Overlapping conspiracies’

As Robertson recalls, by mid-May, “there were many overlapping conspiracies afoot … Within the kava-infused wheels within wheels, coup whispers gained volume”. Ligairi’s role was pivotal but BoI put most of the blame for the coup on the RFMF for “allowing” one man so much power, especially one it considered ill-equipped to be a director and planner’ (p. 140).

The BoI testimony about the November 2000 CRWU mutiny before Bainimarama escaped with his life through a cassava patch, also fed into Robertson’s account, although he admits Colonel Jone Baledrokadroka’s ANU doctoral thesis is the best account on the topic, “Sacred King and Warrior Chief: The role of the military in Fiji politics”.

It was a bloody and confused affair, led by the once loyal [Captain Shane] Stevens, 40 CRWU soldiers, many reportedly intoxicated, seized weapons and took over the Officers Mess, Bainimarama’s office and administration complex, the national operations centre and the armoury in the early afternoon. They wanted hostages; above all they wanted Bainimarama. (p. 164)

The book is divided into four lengthy chapters plus an Introduction and Conclusion – 1. The Challenge of Inheritance about the flawed colonial legacy, 2. The Great Turning on Rabuka’s 1987 coups and the Taukei indigenous supremacy constitution, 3. Redux: The Season for Coups on Speight’s attempted (and partially successful) 2000 coup, and 4. Plus ça Change …? on Bainimarama’s political “reset”. (The Bainimarama success in outflanking his Pacific critics is perhaps best represented by his diplomatic success in co-hosting the “Pacific” global climate change summit in Bonn in 2017.)

One drawback from a journalism perspective is the less than compelling assessment of the role of the media over the period, considering the various controversies that dogged each coup, especially the Speight one when accusations were made against some journalists as having been too close to the coup makers.

One of Fiji’s best journalists and editors, arguably the outstanding investigative reporter of his era, Jo Nata, publisher of the Weekender, sided with Speight as a “media minder” and was jailed for treason.

However, while Robertson in several places acknowledges Nata’s place in Fiji as a journalist, there is no real examination of his role as journalist-turned-coup-propagandist. This ought to be a case study.

Robertson noted how Nata’s Weekender exposed “morality issues” in Rabuka’s cabinet in 1994 without naming names. The Review news and business magazine followed up with a full report in the April edition that year, naming a prominent female journalist who was sleeping with the post-coup prime minister, produced a love child and who still works for The Fiji Times today (p. 118).

Nata then promised a special issue on the 21 women Rabuka had had affairs with since stepping down from the military. However, after Police Commissioner Isikia Savua spoke to him, the issue never appeared. (A full account is in Pacific Journalism Review – The Review, 1994).

NBF debacle

Elsewhere in the book is an outline of the National Bank of Fiji (NBF) debacle that erupted when an audit was leaked to the media: “In fact, the press, particularly The Fiji Times and The Review, were pivotal in exposing the scandal.” Robertson added:

The Review had earlier been threatened with deregistration over its publication of Rabuka’s affair[s] in 1994; now both papers were threatened with Malaysian-style licensing laws to ensure that they remained respectful of Pacific cultural sensitivities and did not denigrate Fijian business acumen. (p. 121)

The bank collapsed in late 1995 owing more than $220 million or nearly 9 percent of Fiji’s GDP – an example of the nepotism, corruption and poor public administration that worsened in Fiji after Rabuka’s coups.

On Coup 1, Robertson recalls how apart from Rabuka’s masked soldiers inside Parliament, “other teams fanned out across the city to seize control of telecommunication power authorities, media outlets and the Government Buildings” (p. 65).

But there is little reflective detail about Rabuka’s “seduction” of the Fiji and international journalists, or how after closing down the two daily newspapers, the neocolonial Fiji Times reopened while the original Fiji Sun opted to close down rather than publish under a military-backed regime.

About Coup 3, Robertson recalls “[Speight] was articulate and comfortable with the media – too comfortable, according to some journalists. They felt that this intimate media presence ‘aided the rebel leader’s propaganda fire … gave him political fuel’. They were not alone’ (p. 154) (see Robie, 2001).

On the introduction of the 2010 Fiji Media Industry Development Decree, which still casts a shadow over the country and is mainly responsible for the lowest Pacific “partly free” rankings in the global media freedom indexes, Robertson notes how it was “Singapore-inspired”. The decree “came out in early April 2010 for discussion and mandated that all media organisations had to be 90 percent locally owned. The implication for the News Corporation Fiji Times and for the 51 percent Australian-owned Daily Post were obvious” (p. 254).

The Fiji Times was bought by Mahendra Patel, long-standing director and owner of the Motibhai trading group. (He was later jailed for a year for “abuse of office” while chair of Post Fiji.) The Daily Post was closed down.

Facing a long history of harassment by various post-coup administrations (including a $100,000 fine in January 2009 for publishing a letter describing the judiciary as corrupt, and deportations of publishers), The Fiji Times is heading into this year’s elections facing a trial for alleged “sedition” confronting the newspaper.

In spite of my criticism of limitations on media content, The General’s Goose is an excellent book and should be mandatory background reading for any journalist covering South Pacific affairs, especially those likely to be involved in coverage of this year’s general election in Fiji.

- The General’s Goose: Fiji’s Tale of Contemporary Misadventure, by Robbie Robertson. Canberra: Australian National University. 2017. 366 pages. ISBN 9781760461270.

References

Baledrokadroka, J. (2012). The sacred king and warrior chief: The role of the military in Fiji politics. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Canberra: Australian National University.

Robertson, R., & Sutherland, W. (2001). Government by the gun: The unfinished business of Fiji’s 2000 coup. Sydney & London: Pluto Press & Zed Books.

Robertson, R., & Tamanisau, A. (1988). Fiji: Shattered coups. Sydney: Pluto Press.

Robie, D. (2001). Coup coup land: The press and the putsch in Fiji. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 10, 149-161. See also for an extensive media coverage examination of the 1987 Rabuka coups: Robie, D. (1989). Blood on their banner: Nationalist struggles in the South Pacific. London: Zed Books; 2006 coup and 2014 elections: Robie, D. (2016). ‘Unfree and unfair’?: Media intimidation in Fiji’s 2014 elections. In Ratuva, S., & Lawson, S. (Eds.), The people have spoken: The 2014 elections in Fiji. Canberra: ANU Press.

The Review (1994). Rabuka and the reporter. Pacific Journalism Review, 1(1), 20-22.