By Nicky Hager, book chapter in Peacemonger

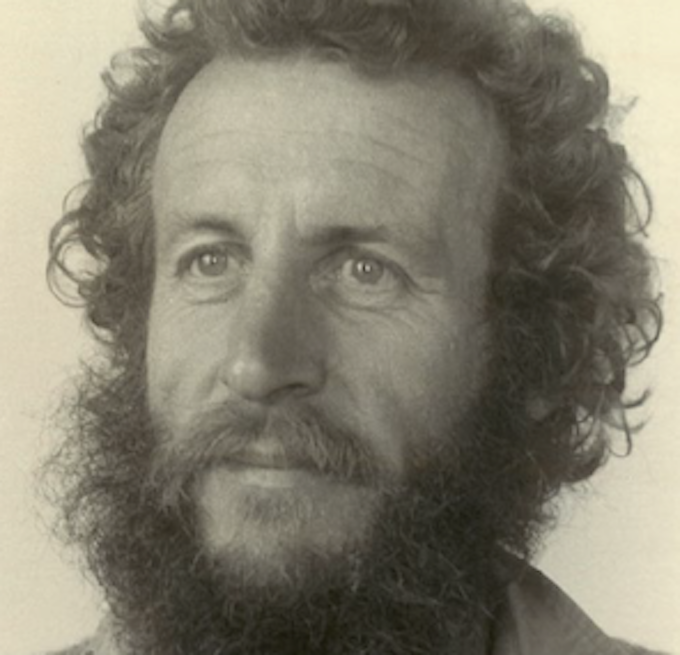

Whistleblower Owen Wilkes was a tireless and formidable researcher for the Pacific, peace and disarmament. Before the internet, he combed publicly available sources on weapons systems and defence strategy.

In 1968, he revealed the secretive military function of a proposed satellite tracking station in the South Island, and while working in Sweden he was charged with espionage and deported after photographing intriguing but publicly visible installations.

In a new book about his life, Peacemonger, edited by May Bass and Mark Derby, Nicky Hager writes about Wilkes’ research techniques:

Owen Wilkes was an outstanding researcher, a role model of how someone can make a difference in the world by good research. But how did he actually do it? Owen managed to study complex subjects such as Cold War communications systems, secret intelligence facilities and foreign military activities in the Pacific.

There are many important and useful lessons we can learn from how he did this work. The world needs more public interest researchers, on militarism and other subjects. Owen’s self-taught research techniques are like a masterclass in how it is done.

Lots of information isn’t secret, just hard to find

Owen Wilkes worked for many years, sitting at his large desk at the Peace Movement office in Wellington, researching the military communications systems set up to launch and fight nuclear war. How was this possible?

We are a bit conditioned currently to imagine the only option would be leaked documents from a whistleblower. The first secret of Owen’s success is that he had learned that large amounts of information on these subjects can be found and pieced together from obscure but publicly available sources.

The heart of his research method was long hours spent poring over US government records and military industry magazines, gathering the precious crumbs of detail like someone panning for gold.

Behind the large desk were shelves and shelves of open-topped file boxes, each with a cryptic title. These boxes were full of photocopied documents and handwritten notes from his researching. This may all sound very pre-internet; indeed it was largely pre-digital.

But what Owen was doing would today be called “open source” research and his work is far superior to that carried out by many people with Google and other digital tools at their fingertips. Probably his favourite source of all was a publicly available US defence magazine called Aviation Week and Space Technology. The magazine (now online) is written for military staff and arms manufacturers, keeping them informed about developments in weapons, aircraft and “C3I” systems, which stands for Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence systems: one of Owen’s main areas of speciality.

The magazine also covered Owen’s speciality of “space based” military systems, such as military communication and surveillance satellites. In Owen’s files, which can be viewed at the National Library in Wellington, Aviation Week and Space Technology appears often. In a file box called USA Space Systems is a clipping from 1983 about the US Air Force awarding a contract for a ballistic missile early warning system (nuclear war-fighting equipment). The article revealed that the early warning system would be based at air force bases in Alaska, Greenland and Fylingdales, England — three clues about US foreign military activities.

By reading and storing away details from numerous such articles, spanning many years, Owen built up a more and more detailed understanding of military and intelligence systems.

The other endlessly useful source Owen used was US Congress and Senate hearings and reports about the US military budget. This is where each year the US military spells out its military construction plans, new weapons, technology programmes and the rest; often with figures broken down to the level of individual countries and military bases.

Senior military officials appear at hearings to explain the threats and strategies that justify the spending. As with the military magazines, Owen systematically mined these reports year after year for interesting detail.

He was especially keen on the US Congress’ Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Military Construction Appropriations. His files on US antisatellite weapons, for instance, contain a document from this subcommittee about new Anti-Satellite System Facilities (project number 11610) based at Langley Air Force base, Virginia. It had been approved by the president in the renewed Cold War of the mid-1980s to target Soviet satellites. Details like this were pieces in a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle.

When he was based at the Peace Movement Aotearoa office in Wellington, from 1983 until about 1992, Owen spent long hours at the US Embassy library studying the Military Construction Appropriations and other US government documents. Each year the library received copies of the documents as microfiche (microphotos of each page on a film). Owen was a familiar visitor, hunched over the microfiche reader making notes and printing out interesting pages.

Many times this gave the first clue of construction somewhere in the world, pointing to that country hosting some new US military, nuclear or intelligence activity. The annual US military appropriation information is available to a researcher today. In fact it is now more easily accessed since it is online. But, if anything, Owen’s pre-digital techniques make it clearer how this research is done well. It’s a good reminder that the best sources of information are most often not in the first 10 or 20 hits of a Google search, the point where many people stop looking.

Experience and persistence

An important ingredient in all these methods is persistence. The methods usually work best if, like Owen, a researcher sticks at them over time. Sticking at a subject means you start to recognise names and places in an otherwise boring document, appreciate the significance of some fragment of information and understand the big picture into which each piece of information fits.

Someone who reads deeply and studies a subject over a number of years can in effect become, like Owen, an expert. They may, like him, have no formal university qualifications. But they can know more about their subject than nearly anyone else, which is a good definition of an expert. They recognise the names and places and appreciate the significance of new evidence.

A textbook example of this was when Owen returned to New Zealand in the early 1980s and went to see a recently discovered secret military site near the beach settlement of Tangimoana in the Manawatu.

Owen, who had spent years studying secret bases around the world, was the New Zealander most likely to know what he was looking at. There, on one side of the base, was a large circle of antenna poles: a CDAA circularly-disposed antenna array. It instantly told him the Tangimoana facility was a signals intelligence base. It had the same equipment and was part of the same networks as the bases he had studied in Norway and Sweden.

Ensuring his research was noticed

The purpose of Owen’s work was to make a difference to the issues he researched. A final and vital part of the work was getting attention for the findings of his research. Owen often spoke in the news and he wrote about the issues he was studying. Research, writing and speaking up are essential ingredients in political change. The part of this he probably enjoyed most was travelling and speaking in public to interested groups.

During the 1980s, he had major speaking tours to countries including Japan, the Philippines, Australia and Canada (and often around New Zealand). During these trips he would present information about military and intelligence activities in those countries. A 1985 trip to Canada, which he shared with prominent Palau leader Roman Bedor, was typical. He was in Canada for seven weeks, speaking in most parts of the country and numerous times on radio and television.

One of the things he emphasised was that Canadians, as residents of a Pacific country, should be thinking about what was going on in the Pacific. One of Owen’s recurrent themes was the importance of being aware of the Pacific.

The final ingredient of a good researcher is caring about the subjects they are working on. This can be heard clearly in everything Owen wrote about the Pacific. He described the Pacific being used for submarine-based nuclear weapons and facilities used to prepare for nuclear war. He talked about the big powers using the Pacific as the “backside of the globe”, epitomised by tiny Johnston Atoll west of Hawai’i where the US military does “anything too unpopular, too dangerous and too secret to do elsewhere”.

He talked about things that were getting better: French nuclear testing on the way out; chemical weapons being destroyed. But also the region being used as a site for great power rivalry; and, under multiple pressures, the small Pacific countries being at risk of becoming “more repressive, less democratic”. He cared, and that was at the heart of being a public-interest researcher for decades.

Many of the problems he described are still occurring today. More research, more good research, on these issues and many others is crying out to be done.

- An extract from Peacemonger – Owen Wilkes: International Peace Researcher, edited by May Bass and Mark Derby. Published by Raekaihau Press in association with Steele Roberts Aotearoa. This article was first published by Stuff and is republished with the book authors’ permission. David Robie is one of the contributing chapter authors.