ANALYSIS: By Richard Falk

Recall Samuel Huntington’s controversial, yet influential, 1993 Foreign Affairs article, “The Clash of Civilizations,” which ends with the provocative phrase, “The West against the rest.” Although the article seemed far-fetched 30 years ago, it now seems prophetic in its discernment of a post-Cold War pattern of inter-civilisational rivalry.

It is rather pronounced in relation to the heightened Israel/Palestine conflict initiated by the October 7 Hamas attack on Israeli territory with the killing and abusing of Israeli civilians and Israeli Defence Force (IDF) soldiers, as well as the seizure of some 200 hostages.

Clearly this attack has been accompanied by some suspicious circumstances such as Israel’s foreknowledge, slow reaction time to the penetration of its borders, and, perhaps most problematic, the quickness with which Israeli adopted a genocidal approach with a clear ethnic cleansing message.

At the very least the Hamas attack, itself including serious war crimes, served almost too conveniently as the needed pretext for the 100 days of disproportionate and indiscriminate violence, sadistic atrocities, and the enactment of a scenario that looked toward making Gaza unlivable and its Palestinian residents dispossessed and unwanted.

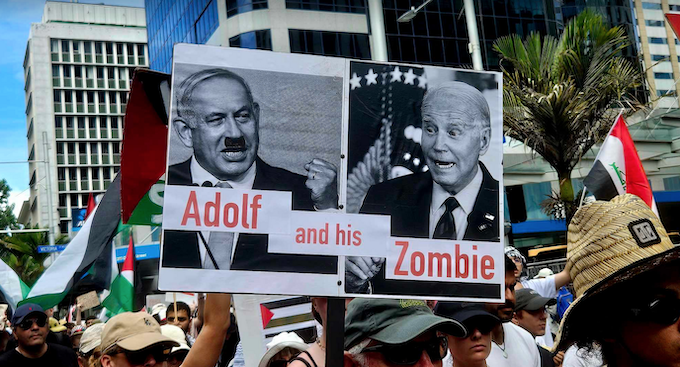

Despite the transparency of the Israeli tactics, partly attributable to ongoing TV coverage of the devastating and heartbreaking Palestinian ordeal, what was notable was the way external state actors aligned with the antagonists. The Global West (white settler colonial states and former European colonial powers) lined up with Israel, while the most active pro-Palestinian governments and movements were initially exclusively Muslim, with support coming more broadly from the Global South. This racialisation of alignments seems to take precedence over efforts to regulate violence of this intensity by the norms and procedures of international law, often mediated through the United Nations.

Liberal democracies failed not only by their refusal to make active efforts to prevent genocide, which is a central obligation of the Genocide Convention, but more brazenly by openly facilitating continuation of the genocidal onslaught.

This pattern is quite extraordinary because the states supporting Israel, above all the United States, have claimed the high moral and legal ground for themselves and have long lectured the states of the Global South about the importance of the rule of law, human rights, and respect for international law. This is instead of urging compliance with international law and morality by both sides in the face of the most transparent genocide in all of human history.

In the numerous pre-Gaza genocides, the existential horrors that occurred were largely known after the fact and through statistics and abstractions, occasionally vivified by the tales told by survivors. The events, although historically reconstructed, were not as immediately real as these events in Gaza with the daily reports from journalists on the scene for more than three months.

Liberal democracies failed not only by their refusal to make active efforts to prevent genocide, which is a central obligation of the Genocide Convention, but more brazenly by openly facilitating continuation of the genocidal onslaught. Israel’s frontline supporters have contributed weapons and munitions, as well as providing intelligence and assurance of active engagement by ground forces if requested, as well as providing diplomatic support at the U.N. and elsewhere throughout this crisis.

These performative elements that describe Israel’s recourse to genocide are undeniable, while the complicity crimes enabling Israel to continue with genocide remain indistinct, being situated in the shadowland of genocide. For instance, the complicity crimes are noted but remain on the periphery of South Africa’s laudable application to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) that includes a request for Provisional Measures crafted to stop the genocide pending a decision on the substance of the charges of genocide. The evidence of genocide is overwhelmingly documented in the 84-page South African submission, but the failure to address the organic link to the crimes of complicity is a weakness that could be reflected in what the court decides.

Even if the ICJ does impose these Provisional Measures, including ordering Israel to desist from further violence in Gaza, it may not achieve the desired result, at least not before the substantive decision is reached some three to five years from now. It seems unlikely that Israel will obey Provisional Measures. It has a record of consistently defying international law. It is likely that a favorable decision on these preliminary matters will give rise to a crisis of implementation.

The law is persuasively present, but the political will to enforce is lacking or even resistant, as here in certain parts of the Global West.

The degree to which the US has supplied weaponry with US taxpayer money would be an important supplement to rethinking the US relationship to Israel that is so important and which is underway among the American people — even in the Washington think tanks that the foreign policy elites fund and rely upon. Proposing an arms embargo would be accepted as a timely and appropriate initiative in many sectors of US public opinion.

I hope that such proposals may be brought before the UN General Assembly and perhaps the Security Council. Even if not formally endorsed, such initiatives would have considerable symbolic and possibly even substantive impacts on further delegitimizing Israel’s behaviour.

A third specific initiative worth carefully considering would be timely establishment of a People’s Tribunal on the Question of Genocide initiated by global persons of conscience. Such tribunals were established in relation to many issues that the formal governance structures failed to address in satisfactory ways. Important examples are the Russell Tribunal convened in 1965-66 to assess legal responsibilities of the US in the Vietnam War and the Iraq War Tribunal of 2005 in response to the US and UK attack and occupation of Iraq commencing in 2003.

Such a tribunal on Gaza could clarify and document what happened on and subsequently to October 7. By taking testimony of witnesses, it could provide an opportunity for the people of the world to speak and to feel represented in ways that governments and international procedures are unable to given their entanglement with geopolitical hegemony in relation to international criminal law and structures of global governance.

The South African World Court case, pariah state, and popular mobilisation

The South African initiative is important as a welcome effort to enlist international law and procedures for its assessment and authority in a context of severe alleged criminality. If the ICJ, the highest tribunal on a supranational level, responds favorably to South Africa’s highly reasonable and morally imperative request for Provisional Measures to stop the ongoing Gaza onslaught, it will increase pressure on Israel and its supporters to comply.

And if Israel refuses to do so, it will escalate pro-Palestinian solidarity efforts throughout the world and cast Israel into the darkest regions of pariah statehood.

In such an atmosphere, nonviolent activism and pressure for the imposition of an arms embargo and trade boycotts as well as sports, culture, and touristic boycotts will become more viable policy options. This approach by way of civil society activism proved very effective in the Euro-American peace efforts during the Vietnam War and in the struggle against apartheid South Africa, and elsewhere.

Israel is becoming a pariah state due to its behaviour and defiance exhibited toward legal and moral norms. It has made itself notorious by its outrageously forthright acknowledgement of genocidal intent with respect to Palestinian civilians whom they are under a special obligation to protect as the occupying power.

We know what we should be doing.to make amends, yet well-entrenched special interests preclude such rational adjustments, and the military malfunctions and accompanying geopolitical alignments persist, ignoring costly failures along the way.

Being a pariah country or rogue state makes Israel politically and economically vulnerable as never before. At this moment, a mobilised civil society can contribute to producing a new balance of forces in the world that has the potential to neutralise Western post-colonial imperial geopolitics.

It is also relevant to take note of the startling fact that the anti-colonial wars of the last century were in the end won by the weaker side militarily. This is an important lesson, as is the realization that anti-colonial struggle does not end with the attainment of political independence. It needs to continue to achieve control of national security and economic resources as the recent anti-French coups in former French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa illustrate.

In the 21st century weapons alone rarely control political outcomes. The US should have learned this decades ago in Vietnam, having controlled the battlefield and dominated the military dimensions of the war, and yet having failed to achieve control over its political outcome.

The US is disabled from learning lessons from such defeats. Such learning would weaken the leverage of the military-industrial-government complex, including the private sector arms industry. This would subvert the domestic balance in the US and substantially discredit the global geopolitical role being played by the US throughout the entire world.

So, it is a dilemma. We know what we should be doing to make amends, yet well-entrenched special interests preclude such rational adjustments, and the military malfunctions and accompanying geopolitical alignments persist, ignoring costly failures along the way.

We know what should be done, but do not have the political clout to get it done. But global public opinion is shifting, and demonstrations globally are building opposition to continuing the war.

Propaganda aimed at Iran

There is a huge US/Israel propaganda effort to tie Iran to everything that is regarded as anti-West or anti-Israeli. It has intensified during this crisis, starting with the October 7 attack by Iran’s supposed proxy Hamas. You notice even the most influential mainstream print media as The New York Times routinely refers to what Hezbollah or the Houthis do as “Iran-backed.” Such actors are reduced misleadingly to being proxies of Iran.

This way of denying agency to pro-Palestinian actors and attributing behavior to Iran is a matter of state propaganda trying to promote belligerent attitudes toward Iran to the effect that Iran is our major enemy in the region, while Israel is our loyal friend. At the same time, it suppresses the reality that If Iran is backing countries and political movements, it obscures what the US is doing more overtly and multiple times over.

It is largely unknown what Iran has been doing in the region to protect its interests. Without doubt, Iran has strong sympathies with the Palestinian struggle. Those sympathies coincide with its own political self interest in not being attacked and minimising the US role in the region. Additionally, Iran has lots of problems arising from opposition forces within its own society.

But I think dangerous state propaganda is building up this hostility toward Iran. It is highly misleading to regard Iran as the real enemy standing behind all anti-Israeli actions in the region. It is important to understand as accurately as possible the complexity and unknown elements present in this crisis situation that contains dangers of wider war in the region and beyond. As far as is publicly known, Iran has had an extremely limited degree of involvement in the direct shaping of the war and Israel’s all-out attack on the civilian population of Gaza.

Hamas and a second Nakba

While I was special rapporteur for the UN on Israeli violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, I had the opportunity to meet and talk in detail with several of the Hamas leaders who are living either in Doha or Cairo and also in Gaza. In the period between 2010 and 2014, Hamas was publicly and by back channels pushing for a 50-year cease-fire with Israel. It was conditioned on Israel carrying out the unanimous 1967 Security Council mandate in SC Res 242 to withdraw its forces to the pre-war boundaries of “the green line.” Hamas had also sought a long-range cease-fire with Israel after its 2006 electoral victory for up to 50 years.

Neither Israel nor the US would respond to those diplomatic initiatives. Hamas, Machel particularly who was perhaps the most intellectual of the Hamas leaders, told me that he warned Washington of the tragic consequences for both peoples if the conflict was allowed to go on without a cease-fire, which was confirmed by independent sources.

Where can Palestinians go as the population suffers from famine and continued bombing? What is Israel’s goal?

All indications are that Israel used the October 7 attack as a pretext for the preexisting master plan to get rid of the Palestinians whose presence blocks the establishment of Greater Israel with sovereign control over the West Bank and at least portions of Gaza.

I see the so-called commitment to thinning the Palestinian presence in Gaza and to a functional second Nakba. This is a criminal policy. I don’t know that it has to have a formal name. It is not a policy designed to achieve anything but the decapitation of the Palestinian population. Israel seeks to move Gazans to the Egyptian Sinai, and the Egyptians have already indicated that they don’t welcome this.

This is not a policy. This is some kind of a threat of elimination. The Israeli campaign after October 7 was not directed toward Hamas’ terrorism nearly as much as it was directed toward the forced evacuation of the Palestinians from Gaza and for the related dispossession of Palestine in the West Bank.

If Israel really wanted to deal with its security in an effective way, much more efficient and effective methods would have been relied upon. There was no reason to treat the entire civilian population of Gaza as if it were implicated in the Hamas attack, and there was certainly no justification for the genocidal response. The Israeli motivations seem more related to completing the Zionist Project than to restoring territorial security.

All indications are that Israel used the October 7 attack as a pretext for the preexisting master plan to get rid of the Palestinians whose presence blocks the establishment of Greater Israel with sovereign control over the West Bank and at least portions of Gaza.

For a proper perspective we should remember that before October 7, the Netanyahu coalition government that took power at the start of 2023 was known as the most extreme government ever to govern the country since its establishment in 1948. The new Netanyahu government in Israel immediately gave a green light to settler violence in the Occupied West Bank and appointed overtly racist religious leaders to administer the parts of Palestine still occupied.

This was part of the end game of the whole Zionist project of claiming territorial sovereignty over the whole of the so-called promised land, enabling Greater Israel to come into existence.

The need for a different context

We need to establish a different context than the one that exists now. That means a different outlook on the part of the Western supporters of Israel. And a different internal Israeli sense of their own interests, their own future. And it’s only when substantive pressure is brought to bear on an elite that has gone to these lengths that it can shake commitments to this orientation.

The lengths that the Israeli government has gone to are characteristic of settler colonial states. All of them, including the US and Canada, have acted violently to neutralise or exterminate the resident Indigenous people. That is what this genocidal interlude is all about.

It is an effort to realise the goals of maximal versions of Zionism, which can only succeed by eliminating the Palestinians as rightful claimants. It should not be forgotten that in the weeks before the Hamas attack, including at the UN, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was waving a map of “the new Middle East” that had erased the existence of Palestine.

Undoubtedly, one of Hamas’ motivations was to negate the view that Palestine had given up its right to self-determination, and that Palestine could be erased. Recall the old delusional pre-Balfour Zionist slogan:

“A people without land for a land without people.”

Such utterances of this early Zionist utopian phase literally erased the Palestinians who for generations lived in Palestine as an entitled Indigenous population. With the Balfour Declaration of 1917, this settler colonial vision became a political project with the blessings of the leading European colonial power.

Given post-colonial realities, the Israeli project is historically discordant and extreme. It exposes the reality of Israel’s policies and the inevitable resistance response to Israel as a supremacist state. Israeli state propaganda and management of the public discourse has obscured the maximalist agenda of Zionism over the years, and we are yet to know whether this was a deliberate tactic or just reflected the phases of Israel’s development.

This may turn out to be a moment of clarity with respect not only to Gaza, but to the overall prospects for sustainable peace and justice between these two embattled peoples.

Dr Richard Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University and served as UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Palestine and is currently co-convener of SHAPE (Save Humanity and Planet Earth). Republished under a Creative Commons licence.