Nicky Hager received a major national award in New Zealand after having written a book exposing a secret spy base in New Zealand and exposing other state crimes, as Murray Horton writes for Covert Action.

By Murray Horton in Christchurch

Julian Assange has, thus far, spent years in a British prison, awaiting extradition to the US, where he faces charges under the Espionage Act, for which he could be sentenced to 175 years in prison. His crime? Journalism.

On the other side of the world, the nation of New Zealand offers a startling contrast in its approach to Nicky Hager, the country’s most famous investigative journalist. New Zealand has an Honours List, announced twice yearly.

This is very much an occasion for the Establishment to pat itself on the back — for example, the June 2023 Honours List featured Jacinda Ardern, the immediate past Prime Minister, being declared a Dame (“for services to the State”) by her successors in government.

But that same list contained something very unusual, unprecedented in fact. An award was given to Nicky Hager, specifically for his investigative journalism. This has never happened before.

And frankly, considering the number of senior politicians and other powerful people that he has pissed off during his nearly 30-year career, it was not something that would have been predicted.

Exposed Waihopai

Nicky is famous globally, not just in New Zealand. He cut his teeth on New Zealand’s successful anti-nuclear campaign of the 1970s and 1980s. He burst into global recognition with his remarkable first book, Secret Power (1996), which was a minutely detailed description of New Zealand’s top secret Waihopai electronic spy base and of the workings of the spy agency which runs it, the New Zealand Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) and of the Five Eyes spy network (US, UK, Canada, Australia and NZ), which provides the international framework for Waihopai and the GCSB.

Secret Power’s Introduction was written by David Lange who, as New Zealand’s Labour Prime Minister in the 1980s, had both steered the country to the nuclear-free status that it enjoys until today, and authorised the construction of the Waihopai spy base. Lange confessed that he learned more about Waihopai from Nicky’s book than he ever did when he was prime minister, and was supposedly in charge of the intelligence agencies.

Secret Power was just the first of seven books (so far). Secrets and Lies (1999) was about the secret campaign of a former state-owned enterprise to win public support for the logging of native forests and to smear environmental groups.

Seeds of Distrust (2002) was about lobbying and cover-ups concerning genetic modification (which remains banned in New Zealand). This was released just as the Labour Government called a snap election, and the appearance of Nicky’s book seriously pissed off Prime Minister Helen Clark.

Brought down right-wing Leader of Opposition

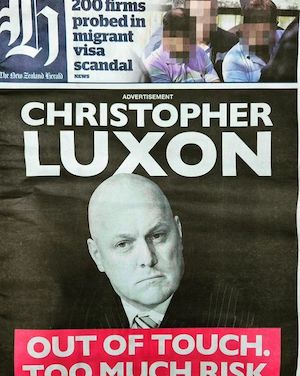

Two of Nicky’s books have lifted the lid on the cesspool of politics in New Zealand and each has had a major impact. The Hollow Men (2006) exposed the secret funding of the opposition National Party’s 2005 election campaign advertising by the obsessively secretive Exclusive Brethren Church. The resultant uproar led to the resignation of the National Party Leader.

Dirty Politics (2014), published in an election year, examined the links between senior figures in the National Party (by now back in government) and various unsavory right-wing attack trolls and bloggers. This created such a sensation that “dirty politics” entered the language to describe a particular modus operandi by behind-the-scenes political operators.

Unearthing truth about special forces

And two of Nicky’s books, Other People’s Wars (2011), and Hit & Run (2017), have focused on the activities of the New Zealand military in Afghanistan.

The most recent of those forensically examined the activities of the Special Air Service (SAS) in a retaliatory raid on two Afghan villages that led to civilian deaths. The National government declined calls for a commission of inquiry. But the new Labour government decided to hold one (a former prime minister was one Commissioner).

In 2020 it released a number of findings critical of the New Zealand Defence Force and made a number of recommendations, including the creation of an Independent Inspector-General of Defence. When releasing the report, the Attorney-General said: “Without the book, the findings of the report and its important recommendations would not have been possible. Given this, it is right to acknowledge, as does the report, that the book has performed a valuable public service.”

Cops and spies have had to apologise to him, pay damages

Nicky has never been charged with anything or been sued by anyone. But the state has gone after him — and lost every time. In June 2018, he accepted an apology and compensation for “substantial damages” from the New Zealand Police for raiding his home in 2014 as part of their investigation into the hacking that led to the Dirty Politics book. The police also acknowledged accessing his financial records as part of the apology settlement.

In 2019, the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (SIS) was ordered to formally apologise to Nicky for unlawfully obtaining and using two months of his phone records to try to find his military source(s) for Other People’s Wars. In 2022 the SIS was ordered to back up that apology with a payment of NZ$66,000 damages and costs, in return for Nicky settling the case out of court.

None of Nicky’s sources, ranging from spies to Special Forces soldiers to political insiders, has ever been outed. He has gone from being routinely branded a “conspiracy theorist” by very senior politicians and their media mouthpieces to being recognised as a vital part of a functioning democracy.

He is a truly independent journalist in the best Kiwi do-it-yourself tradition. He has never worked for any media outlet. His previous job was as a builder (he built his own Wellington hillside home).

And he is extremely popular. After his award was announced, he told TVNZ’s 1 News: “I couldn’t go out on the street or to the supermarket for maybe a year or two after [publishing Dirty Politics] without someone coming up to congratulate me. I was blown away.

“Walking the dog out and about, every single time, there would be at least one person who thanked me. So, I don’t feel deprived of good feedback from the public.”

“But he says he’s not planning on stepping back from his work any time soon. ‘I want to say this very clearly—this is not an end-of-career award for me. There are many big projects, good projects coming down the line.’

So, people in power should watch out? He just nods and smiles.”

Standing on the shoulders of giants: Owen Wilkes

Nicky deserves all the kudos he has coming to him but he did not materialise out of thin air. He started off in the peace movement, working with New Zealand’s greatest peace researcher, Owen Wilkes (1940-2005).

They were an interesting mix of styles and tradecraft. Nicky’s specialty has been getting insiders and whistleblowers to spill the beans, along with an uncanny ability to research and find out things by first-hand observation (he took a mainstream TV reporter inside the Waihopai spy base and they were able to film right into the place because the spies did not close their curtains properly).

Owen had an astonishing ability to read thousands of eye-glazing pages of US government and military documents to extract the kernels of truth hidden within. Plus, he had a classic Kiwi DIY research approach. I can give you two examples from personal experience. He spent six years in Scandinavia in the 1970s and 1980s, working for two prestigious peace research institutes (and getting prosecuted under Norway and Sweden’s Official Secrets Acts for finding out too much of what they were up to).

I, and my then-partner, accompanied him on a research trip to northernmost mainland Norway, an area of NATO spy bases close to the Soviet Union. Owen parted company with us for a while and headed off on his own. It was only decades later that I learned that he had actually clandestinely entered the Soviet Union, fording an Arctic border river wearing his trademark shorts.

He lived to tell the tale, although God knows what would have happened if he had been caught, in the Cold War world of 1978.

The other example was in New Zealand, during the 1980s. He drove me to a GCSB spy base, straight up into the place in broad daylight. He was hardly inconspicuous: no driver’s license, shorts, bare feet. Oh, and he was wearing a red cap labeled “KGB Agent” that he had bought at a rummage sale.

Once we had parked, he invited me to join him in climbing the fence and pacing out the distance between aerials to assist his calculations. I can still remember the sunlight glinting off the binoculars as the spies watched us from the main building.

Long overdue recognition

For a quarter of a century (from the late 1960s until the early 1990s) Owen was the global expert on US military and spy bases in New Zealand, Australia, and other countries, such as the Philippines and Japan. He has been dead nearly 20 years but he is now getting the recognition he deserves. In 2022, he was the subject of Peacemonger, a book of essays about him by writers from around the world.

I wrote the essay on him and the anti-bases campaign; Nicky wrote the essay on Owen’s tradecraft. And the mainstream media are getting on the band wagon.

In June 2023, New Zealand’s biggest chain of newspapers put him on the cover of its weekly lifestyle magazine, with a four-page spread inside that reads: Nicky Hager and Owen Wilkes, two of New Zealand’s greatest taonga [treasures]—gifted to the world.”

Murray Horton is organiser of the Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) and an advocate of a range of progressive causes for the past four decades. He has also contrinbuted several articles to Café Pacific. He can be reached at: cafca@chch.planet.org.nz.

This article was first published by Covert Action Magazine and is republished by Café Pacific with the permission of both the author and Covert Action Institute. Donations to the magazine support investigative journalism. Contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the magazine.