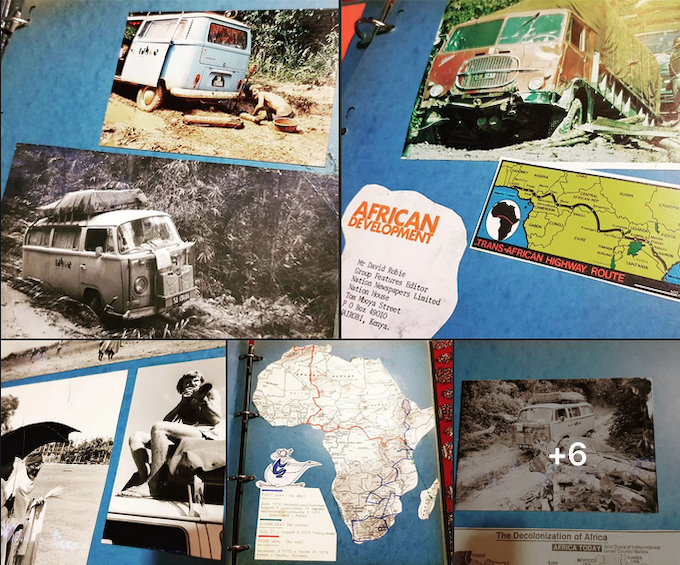

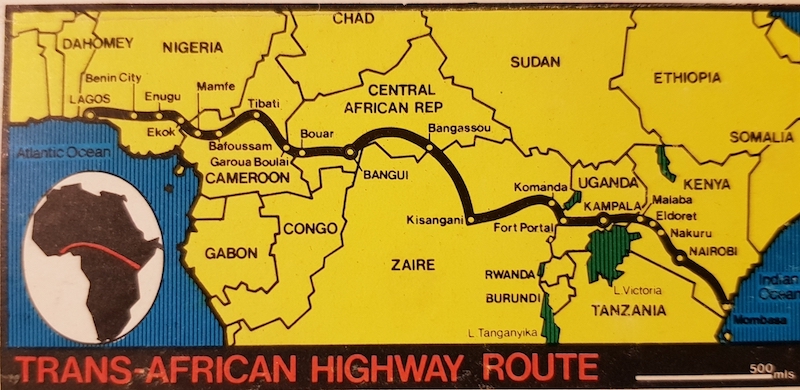

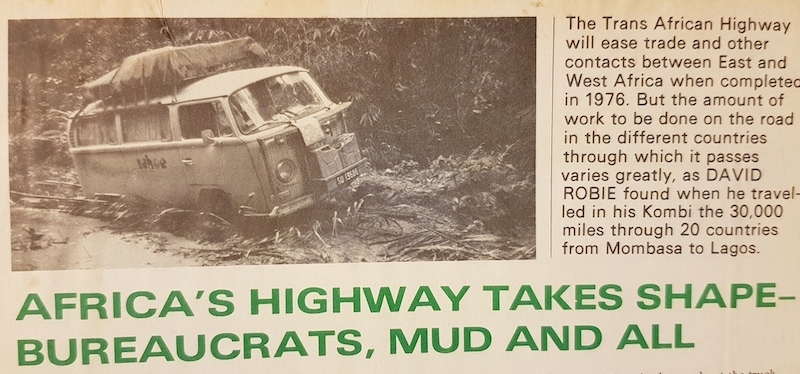

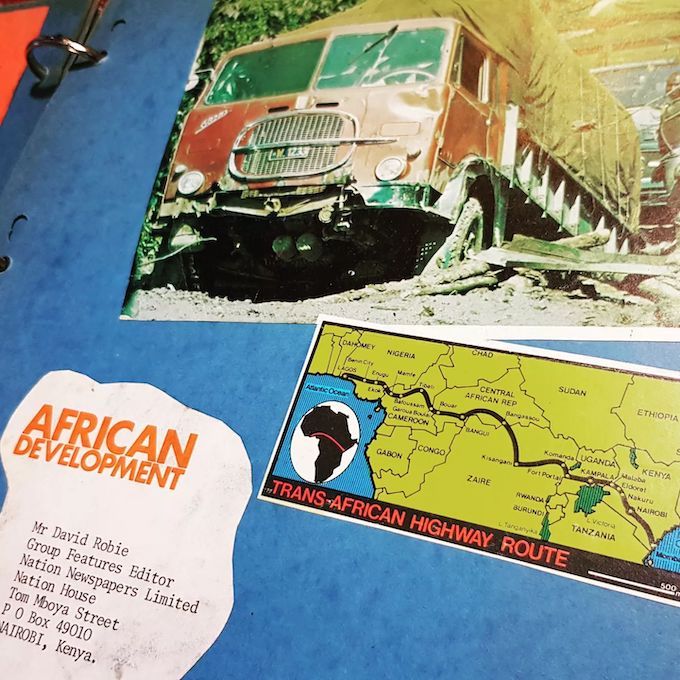

Flashback to a cover story in African Development magazine in April 1974. The Trans-African Highway (TAH) was expected to ease trade and other contacts between East and West Africa when completed in 1976. But the amount of work to be done on the road in the different countries through which it passed varied greatly, as David Robie found when he travelled in his Kombi across more than 6400 kilometres from Mombasa (Kenya) to Lagos (Nigeria). This was part of Robie’s epic African odyssey in the blue Kombi named “Tūhoe” in honour of the Te Urewera people from Cape Town to Algiers and then on to Paris via Ceuta, Morocco.

By David Robie

Africa’s prestige road, the Trans African Highway (TAH) from the Kenyan port of Mombasa on the shores of the Indian Ocean to the hectic Nigerian capital Lagos on the Atlantic, is taking shape mile by mile.

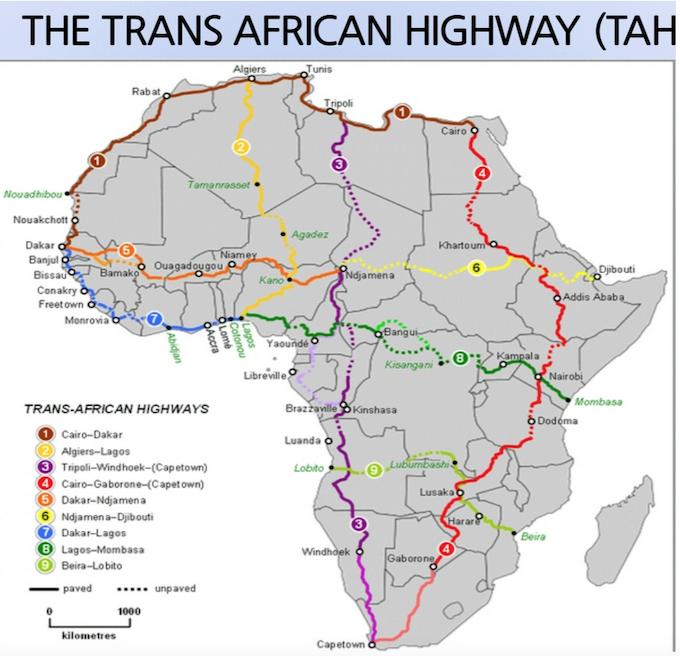

The 4000 mile (6438 km) route through Kenya, Uganda, Zaire, Central African Republic, Cameroon and Nigeria will be completed within four years, according to experts at the highway’s coordinating conference in Mombasa last year.

Dr Robert Gardiner, executive secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, is even more optimistic. “With determination and readiness,” he says, “the first inaugural trip to Lagos will be made in 1976.”

The projected route, starting in Kenya, climbs from Mombasa to Nairobi, follows the highlands to Eldoret and drops away to the Ugandan border. Through Uganda it crosses the Victoria Nile to Kampala and then skirts the Ruwenzori — the fabled Mountains of the Moon.

Yaoundé bypassed

In Zaire, the route penetrates almost 1000 miles of tropical jungle, including the wild Ituri forest, home of the pygmy tribes. It meets the Zaire river (former Congo) at Kisangani, the dreary capital of Upper Zaire province. From Bangassou, the route crosses rolling countryside of the Central African Republic to chic Bangui and on to the Cameroon border.

Across Cameroon it is ill-defined. The major port of Douala and the capital Yaoundé are being bypassed in favour of a route further north through Tibati, crossing several old Fon kingdoms and straddling the Cameroon highlands. From the Nigerian border it carries on through scrubland to Enugu, Onitsha, across the mighty Niger river, and into the forest again to Benin City and Lagos.

Kenya and Uganda’s share of the roads are mainly asphalt and little needs to be done. Nigeroa’s roads are mainly asphalt, too, but many of them were badly damaged during the three-year Nigerian civil war (6 July 1967 – 15 January 1970) fought with the secessionist republic of Biafra. Most of the rest of the route — particularly through Zaire — is in a bad way.

At independence in 1960, Zaire had a comprehensive system of roads in the north-east region. However, the roads have been severely neglected in the last decade and some are now the worst on the whole Trans-African route.

For nine month of the year heavy rain turns roads in the Zaire basin into treacherous slush. For the other three months the tracks dry out a little but many sections remain difficult, if not impassable, for vehciles without four-wheel drive (even Land-Rovers often find them too much).

I crossed Zaire during December, one of the “drier” months. There was no rain in 15 days of driving , but the worst leg of the highway — between the tiny village of Tele and the derelict town of Buta — was 50 miles (80 km) of 3ft (1m) deep mudholes and scoured out ridges.

It took almost three days to battle my way through the worst part — nine hours to go merely one mile (1.6 km). I picked up a soldier and a labourer (they were seeking a lift to their village) for extra pushing power. They were invaluable for recruiting whole groups of villagers to help out in trouble spots — for negotiated fees of 10 makuta a head (about 9p), bars of soap, bags of sugar, old sandals or shorts, or something similar.

But even with 20 men pushing and preparatory swork with tree trunks cut from the forest and a high-lift jack it took three hours of solid work getting through the worst holes.

The road is considered a “hell run” by Zairean drivers. It is only 200 miles (322 km) from Kisangani to Buta, but they prefer to drive 840 miles (1352 km) through Isiro than to tackle the Tele road.

Yet trucks continually get bogged elsewhere. Midway between Mambasa and Nia-Nia I encountered a truck which had been trapped in a 4ft (1.2m) deep mudhole for 14 hours. Rescuers struggled to free it, but on each attempt it was sucked deeper into the putrid mire so that the tray was level with the track.

On one side 12 trucks were held up waiting to get through and on the other side there were eight. There was no way around because the jungle grew right to the edge of the road.

A road gang eventually arrived, towed out the truck and filled in the giant hole — but not before 30 trucks had piled up waiting to get through.

The drivers take these episodes in their stride. An everyday hazard of Zairean roads.

Bridges in Zaire are also neglected. When planks rot , they are often not replaced and many bridges have gaping holes; north of Kisangani there are makeshift bridges of split logs.

Four river ferries ply the route north of Kisangani, too. Across the Aruwimi River at Nanalia there is a modern 30-tonner, at Bondo there is a 20-tonner, and one near Monga is poled across the river.

The ferry across the Ubangi River from Ndu to Bangassou is operated by a 24-volt electrical system — but the batteries have been stolen (three years ago). Travellers or truck drivers must provide their own batteries or hire a pirogue (dugout boat) to borrow batteries from the mission at Bangassou.

Zairean government ferries are free, but many crews, especially on the Ubangi, take advantage of their isolation to coerce fat tips from passengers.

Huge trees sometimes tumble across roads and travellers have to force a trail through the forest until a path has been cut through the trunk.

Conditions are generally far better in the other highway countries. The Central African Republic has mainly good roads with a few eroded patches and sand drifts in border areas.

Cameroon’s roads in the Tibati region are extremely bad, but better than in Zaire. Kenya and Uganda have first-class roads.

Nigeria has a mixed bag — excellent roads in some places and badly chopped up roads elsewhere.

A 2021 TAH news item on the New Africa Channel.

£200m — £300 being spent

Finance for development of the highway is being provided mainly by grants and sft loans from Belgium, France, Italy, Japan, United States, West Germany, the African Development Bank and the World Bank. Conflicting estimates on total spending vary between 200 million and 300 million pounds sterling.

About 50 percent of the road studies have been completed, 40 percent are assured of financial backing and only 10 percent remain outstanding.

Highway specifications call for 24ft-wide (7.4m) roads with 9ft (2.7m) shoulders capable of supporting vehicles driving at 60 mph (97 kph). Maximum loadings are not yet determined. French-speaking countries support 13 tonnes and the English-speaking nations prefer 10 tons.

Zaire has embarked on a £50 million programme (including an £8 million IDA loan) to develop 1300 miles (2010km) of roads in its north-eastern region. Most of this money will be spent on the Trans African Highway yet the Offices des Routes gives some priority to regional roads such as a new one being prepared from Kisangani through Walikale to Goma on Lake Kivu.

The Belgian-Zaire company Sonozatra has begun improving most of the rioad from Beni to Kisangani. It has already upgraded 205 miles (330 km) from Nia-Nia to Kisangani. Dumez-Zaire, a French company, is working on the on the Kisangani to Buta sector and a yet to be named Japanese comoany will this year begin work from there to the border.

Cameroon also has wide-ranging plans for developing the highway. In a bold move, the Transport and Planning Ministries preferred to ignore the existing reasonable road through Yaoundé and Douala. Instead, it has chosen to construct a road through Tibati to open up bauxite-rich areas near the railhead town Ngaoundere and to develop areas around the Adamaoua foothills which have a high potential for cattle ranching, and rice and maize cultivation.

West German consultants DIWI are studying the possibility of routing the road through the Mbam valley to Magba. The Italian company SIPAC has started work on Meidouga to Tibati. Garoua-Boulai to Meidouga will be left for the moment because highway funds have been diverted to buold a good road from Tibati to Ngaoundere.

The Highways Department is at present constructing a new road from Mamfe to Bamenda and tenders will soon be called for the Bafousem to Foumban road.

About £40 million is being allocated (mainly through USAID, West German and Italian loans) for these projects.

In the Central African Republic, funds are short but 70 miles (113 km) of asphalt is expected to be laid between Damara and Sibut and the French company BCEOM is upgrading 200 miles (322 km) from Bossemtele to Garoua-Boulai.

Uganda will lay asphalt on the last earth road remaining on its share of the route — about 100 miles (161 km) between Kampala and Fort Portal. Kenya generally has good tarmac roads up to the highway specifications.

Nigeria is spending up to £80 million in an impressive programme, including the Lagos to Shagamu leg of a planned freeway to Ibadan. Monier is rebuilding war-damaged bridges and Dumez-Nigeria will construct others between Shagamu and Benin City.

Dumez-Nigeria has just completed the $4.5 million Benin to Onitsha road and repairs to the Niger bridge will be completed this year. Tenders will soon be called for the shell-pocked Onitsha to Enugu and Enugu to Bamilike roads. A feasibility study is being carried out on the Bamileke to Ekok earth road which becomes impassable during the rains.

Connecting the giant highway will be the two proposed Trans West African Highways and feeder roads in the east from the Somali capital Mogadishu to Nairobi (800 miles — 1290 km), the Zambian capital Lusaka to Nairobi (1500 miles — 2415 km), the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa to Nairobi (1000 miles — 1600 km), the Sudanese capital of Khartoum to Kampala (1350 miles — 2173 km), and Bujumbura in Burundi to Kasindi in Uganda (500 miles — 800 km).

More than 4000 miles (6438 km) of similar roads will link the main urban centres of Chad, Congo, Gabon and Niger with the highway.

Some of these roads, such as from Lusaka to Nairobi, already have lengthy asphalt stretches up to standard. Work on others, such as Mogadishu to Nairobi, will largely be started from scratch. And when the roads are completed there is the difficulty of maintenance. Many of the highway countries are budgeting adequately for road construction but there the money ends.

“The trouble is that many African countries don’t understand the importance of maintenance,” said one engineer in Yaoundé. “They think that once you’ve built a good road, it will look after itself.”

Common customs, immigration procedures

Perhaps a greater problem than the roads themselves will be persuading the six countries to agree on common customs and immigration procedures, extension of in-bond facilities for transit goods between ports and landlocked nations, vehicle insurance, road regulations, and perking up border efficiency.

When I was leaving Zaire, a couple who had broken down and overstayed their eight-day transit visa had a torrid time with the immigration official. He insisted they must return more than 500 miles (800 km) across bad roads to Kisangani to straighten out the issue.

At last he relented — for a bribe of US$4 and tucked the greenbacks inside the flyleaf of a Bible.

Nigerian customs officials refused me entry at first because my Kenyan-issued international driver’s permit did not include Nigeria in the list of countries on the cover. And then they refused to accept that there was such an vehicle engine number as the one listed in my West Ger man-issued carnet de passage. It took almost three hours before the officials finally let me cross the border.

In Uganda, soldiers rifled through my gear looking fir “guns” while I was leaving the country and troops in Zaire commandeered my van at gunpoint for a joyride (to a nearby village). But these episodes are nothing compared with what many truck drivers experience.

In spite of fuel shortages in many parts of Africa there are serious difficulties only in Zaire on the highway route. When I travelled through it was only possible to buy petrol in three towns — Beni, Kisangani and Bondo – in almost 1000 miles (1600 km).

And it is difficult changing money in Zaire. Bondo,like many towns, had no banking facilities whatsoever, forcing people to resort to currency black markets merely to buy petrol.

Premium grade petrol prices vary from 27p a gallon in oil-rich Nigeria (pegged throughout the country) to nearly 70p in Bangassou, Central African Republic.

Four of the highway ciuntries drive on the right. Only Kenya and Uganda will have to be persuaded to follow suit. London consultants T P O’Sullivan and Partners and the Paris-based Bureau Central d’Etudes pour les Equipments have been commissioned by the Economic Commission for Africa to investigate this sort of problem and make recommendations on hos the six countries can adopt compatable systems. They are expected to present a preliminary report to the highway coordinating committee’s conference from April 3 to 7, 1974.

“When the concept of the highway was raised,” said Kenya’s Vice-President Daniel Arap Moi last year, “many of our friends laughed at us and thought this was one of those white elephants.”

It still has a long way to go but the Trans African Highway will certainly be no white elephant. It will give trade and contact between East and West Africa a tremendous shot in the arm.

This article was originally published by African Development magazine in April, 1974 (pp. 11-13).