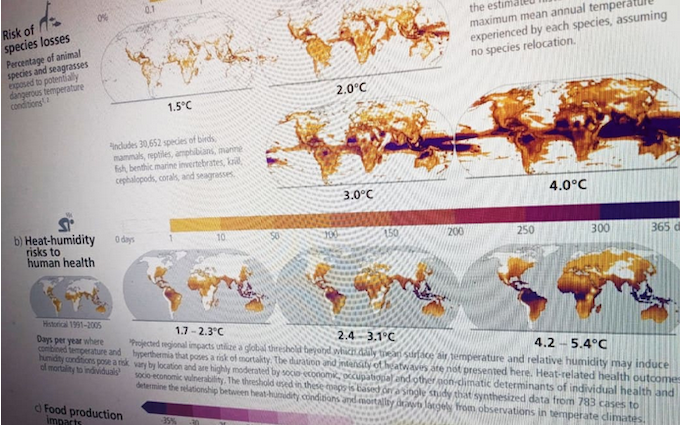

Monday’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report has given a “final warning” to avert global catastrophe. Pacific cabinet ministers call on all world leaders to urgently transition to renewables.

COMMENT: By Ralph Regenvanu and Seve Paeniu

The cycle is repeating itself. A tropical cyclone of frightening strength strikes a Pacific island nation, and leaves a horrifying trail of destruction and lost lives and livelihoods in its wake.

Earlier this month in Vanuatu it was two category 4 cyclones within 48 hours of each other.

The people affected wake up having nowhere to go and lack the basic necessities to survive.

- READ MORE: Some Pacific nations ‘won’t survive’ if NZ and world drop the climate ball

- Port Vila call to phase out fossil fuels

- UN calls for rapid, ambitious action to tackle climate crisis

- IPCC report: world must cut emissions and urgently adapt to climate realities

- The AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023

International media publishes grim pictures of the damage to our infrastructure and people’s homes, quickly followed by an outpouring of thoughts, prayers and praise for our courage and resilience.

We then set out to rebuild our countries.

The Pacific island countries are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, and Vanuatu is the most vulnerable country in the world, according to a recent study. Our countries emit minuscule amounts of greenhouse gases, but bear the brunt of extreme events primarily caused by the carbon emissions of major polluters, and the world’s failure to break its addiction to fossil fuels.

The science is clear: fossil fuels are the main drivers of the climate crisis and need to be phased out rapidly, as the new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report once again confirms. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has shown that ending the expansion of all fossil fuel production is an urgent first step towards limiting warming to 1.5C.

Driven by greed

The climate crisis is driven by the greed of an exploitative industry and its enablers. It is unacceptable that countries and companies are still planning to produce more than double the amount of fossil fuels that the world can withstand by 2030 if we are to limit warming to 1.5C, a limit Pacific countries fought hard to secure in the Paris agreement.

As the UN Secretary-General António Guterres has repeatedly declared, fossil fuels are a dead end. Governments must pursue a rapid and equitable phase-out of fossil fuels.

Countries cannot continue to justify new fossil fuel projects on the grounds of development, or the energy crisis. It is our reliance on fossil fuels that has left our energy infrastructure vulnerable to conflict and devastating climate impacts, left billions of people without energy access, and left investment in more flexible and resilient clean energy systems lagging behind what is needed.

Transitioning away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy is crucial to mitigating the impacts of climate change and ensuring a sustainable future for Pacific island countries and the world.

This requires ambitious collective effort from governments, businesses and individuals around the globe to transition towards renewable energy systems that centre the needs of communities and avoid replicating the harms of fossil fuel systems, while supporting those most affected by the transition.

Transitioning to clean energy and battling climate change is also a human rights and justice issue. This is why our countries will soon be asking the UN General Assembly to request an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice on the obligations of states under international law to protect the environment and the climate.

We urge all countries to support us in that endeavour.

Planning our transition

We acknowledge that Pacific countries are still reliant on fossil fuels for our daily lives and our economy. This is why we are planning our own just transition.

Last week, Pacific ministers and international partners met in cyclone-stricken Vanuatu to chart our collective way forward. We have affirmed a new commitment to work tirelessly to create a fossil fuel free Pacific, recognising that phasing out fossil fuels is not only in our best interest to avoid the worst of climate catastrophe — it is also an opportunity to promote economic development and innovation that we must seize.

By investing in renewable energy sources, we can build resilient, sustainable economies that benefit our people and the planet; and momentum for this shift is already building.

Last year at Cop27 in Egypt, more than 80 countries supported the phasing out of all fossil fuels. We must drive this new ambition around the world. Pacific nations will continue to spearhead global efforts to achieve an unqualified, equitable end to the world’s dependence on fossil fuels.

We will raise our collective voices at Cop28 and through leading initiatives such as the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance and the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty.

We know what needs to be done to keep 1.5C alive, and are aware of the small and shrinking window which we have left to achieve it. We are doing our part and urge the rest of the world to do theirs.

Ralph Regenvanu is Vanuatu’s Minister of Climate Change, Adaptation, Meteorology and Geohazards, Energy, Environment and Disaster Risk Management. Seve Paeniu is the Minister of Finance for Tuvalu. This article was first published by The Guardian and has been republished with the permission of the authors.