By Miriam Zarriga in Port Moresby

Since the start of Papua New Guinea’s Operation Stabilising Oro last month, 22 rape, murder and armed robbery suspects have been to date charged — and more are to follow.

There is also an estimated backlog of 105 outstanding cases that will be attended to over the next three to four weeks with more arrests to follow.

“We have confiscated home brew equipment, home and factory-made firearms, wire catapults and large quantities of drugs,” Oro provincial police commander Chief Inspector Ewai Segi said.

“The fight against crime has commenced after several armed robberies, shootings and the tag of ‘cowboy country’ only fueled the rise in crime reports.

“Families, women and girls were victims of the so-called ‘don’t care’ gang who robbed anyone anywhere and struck fear in the hearts of many residents.

“Police have exhausted everything within their power to curb crime but failed miserably because of shortages in manpower and other resources, thus the entry of the support of the Water Police, NCD Forensics and police prosecution to rid crime and also move along criminal cases.

“Traffic enforcement using the latest charge sheet from the National Road Transport Authority are also in full swing where offenders face charges up to K2000 (NZ$890) and defaults of up to K10,000 (NZ$4,450) and or imprisonment and my orders are very concise.”

Joint operations briefing

Chief Inspector Segi made this observation during the joint operations briefing in Popondetta on Saturday, January 14, where he addressed members of the NCD contingent lead by Contingent Commander Justus Baupo and his special operations team.

Governor Gary Juffa who was with the team when they started operations two weeks ago also expressed his gratitude to the local police force for stepping up during very trying times to uphold the rule of law.

“I am proud of our local troops as despite very small numbers they continue to work tirelessly to uphold the law and maintain order in Oro,” Juffa said.

“With this additional support from NCD [National Capital District], I am confident our local troops will be able to triple their current efforts and rid our rural communities and urban settlements of ruthless criminal elements and regain the confidence of the wider community.”

According to Governor Juffa, there are plans already afoot to have support from NCD specific to Forensic and Prosecution to see through a lot of outstanding cases which the PPC had highlighted earlier.

“Operation Stabilising Oro is a full-scale operation where we deployed a traffic team, an Investigative Task Force (ITF) unit backed by an armed team from Water Police,” Chief Inspector Segi Segi said.

“I am very pleased to announce we have made a record number of arrests and charges laid successfully on perpetrators who had been on the run for some time and continuous raids on hotspot areas confiscating home brew implements, home and factory-made firearms, the infamous wire catapult and large quantities of drugs.

Rallied community support

“I have rallied the support of the wider community, especially clans and tribal chiefs, to stand with me and the Governor Gary Juffa to ensure Oro is stabilised and returned to normalcy before the first quarter of 2023 concludes.

“On the investigative task force front, we have made available full support to the joining ITF team through collaboration to reduce the vast number of pending and outstanding cases back some five years or more.

“Our collaboration in terms of information and intel sharing and interview records and access to our case database are priority areas and I am confident we will see successful prosecution in the coming days and weeks.”

Provincial Administrator Trevor Magei confirmed also that a lot of the ongoing criminal challenges were caused by the same known criminal elements.

“They continue to cause havoc because we lacked proper resourcing within our ITF and prosecution, but from my monitoring there is hope for Oro as we have a very good composition of police support from police headquarters,” he said.

Magei is also head of the provincial law and order working committee and has assured Chief Inspector Segi and staff from outside Oro of more collaboration as they continue in the coming weeks.

“The business community, the local chamber of commerce, our Chinese business association together with major employer Sime Darbie are all backing this special operation with whatever support and logistics they can contribute,” he said.

Miriam Zarriga is a senior PNG Post-Courier reporter. Republished with permission.

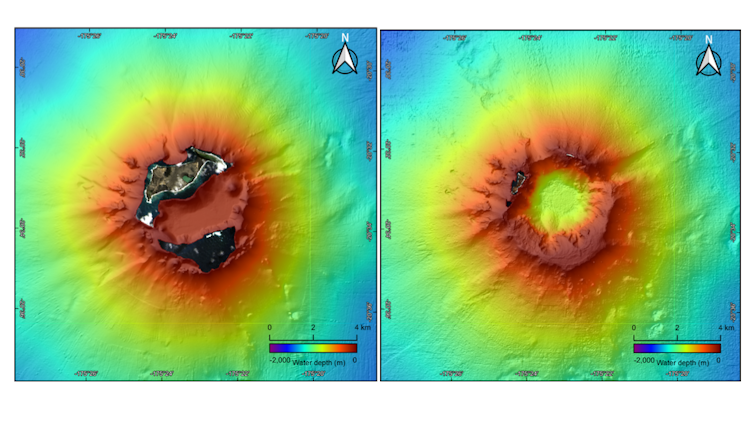

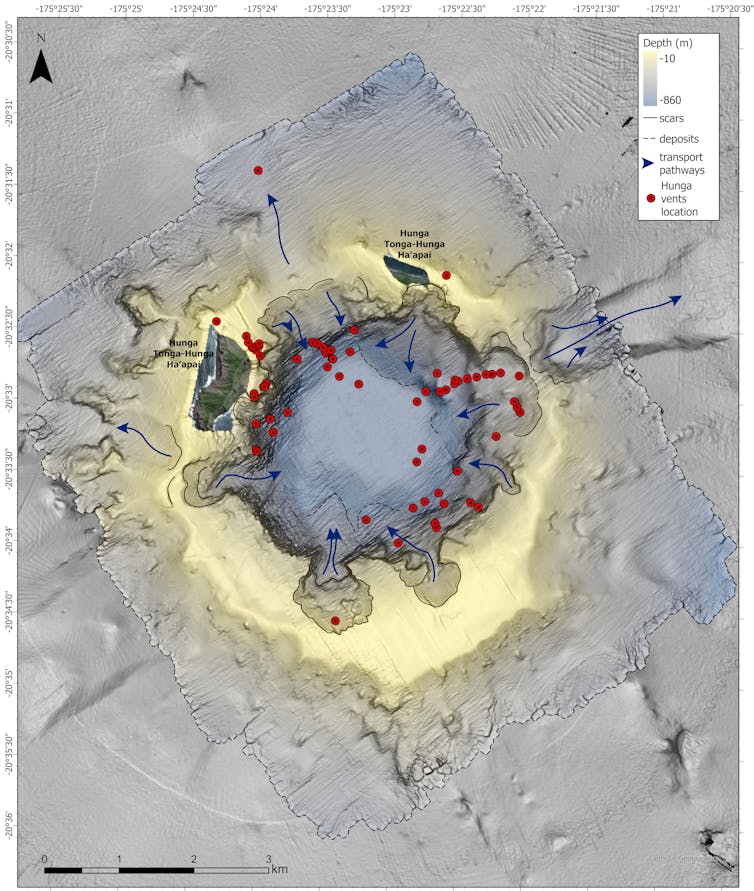

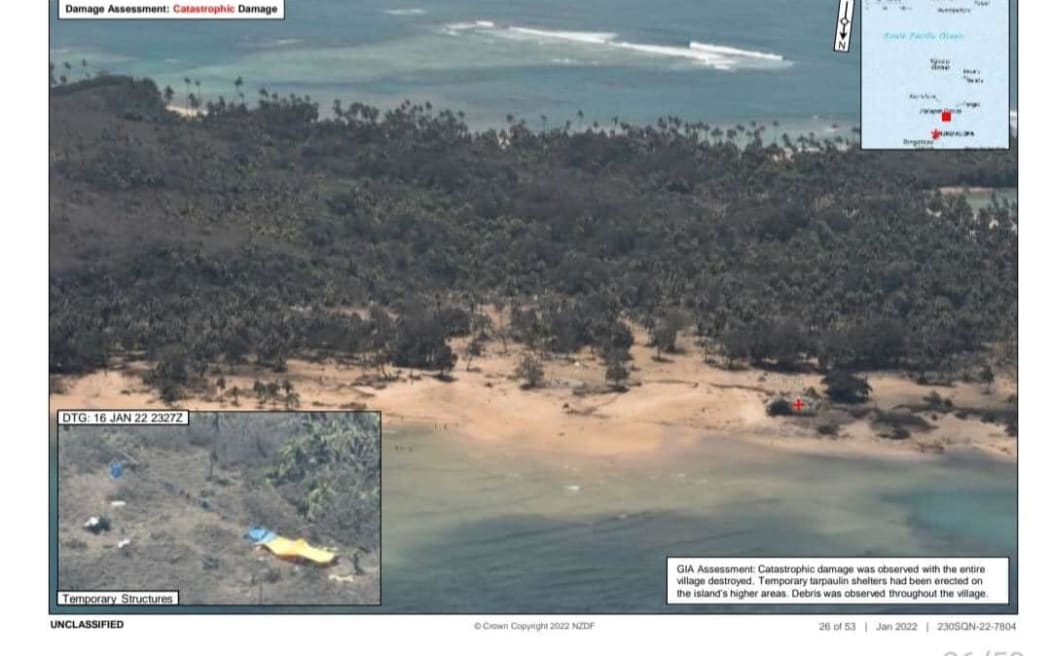

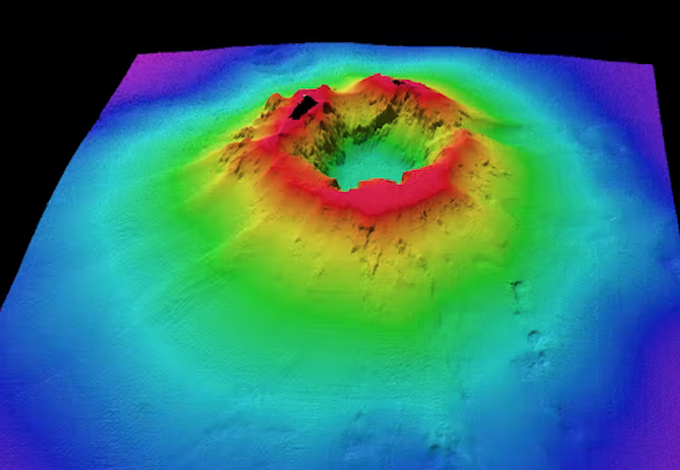

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption has firmly established itself in the record books with the highest ash plume ever measured.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption has firmly established itself in the record books with the highest ash plume ever measured.