COMMENTARY: By Eugene Doyle

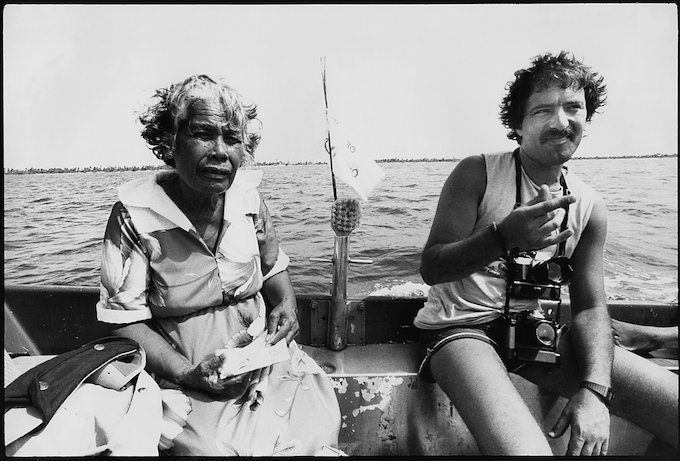

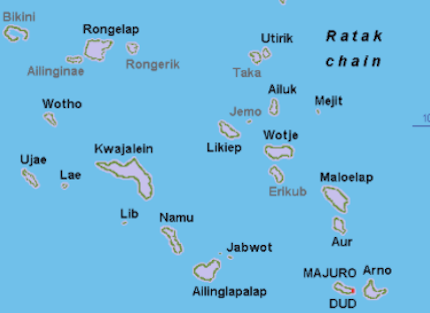

On the last voyage of the Rainbow Warrior prior to its sinking by French secret agents in Auckland harbour on 10 July 1985 the ship had evacuated the entire population of 320 from Rongelap in the Marshall Islands.

After conducting dozens of above-ground nuclear explosions, the US government had left the population in conditions that suggested the islanders were being used as guinea pigs to gain knowledge of the effects of radiation.

Cancers, birth defects, and genetic damage ripped through the population; their former fisheries and land are contaminated to this day.

- READ MORE: The Rainbow Warrior saga: 1. French state terrorism and NZ’s end of innocence

- Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage and Legacy of the Rainbow Warrior

- Other Rainbow Warrior reports

Denied adequate support from the US – they turned to Greenpeace with an SOS: help us leave our ancestral homeland; it is killing our people. The Rainbow Warrior answered the call.

Human lab rats or our brothers and sisters?

Dr Merrill Eisenbud, a physicist in the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) famously said in 1956 of the Marshall Islanders: “While it is true that these people do not live, I might say, the way Westerners do, civilised people, it is nevertheless also true that they are more like us than the mice.”

Dr Eisenbud also opined that exposure “would provide valuable information on the effects of radiation on human beings.” That research continues to this day.

A half century of testing nuclear bombs

Within a year of dropping nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the US moved part of its test programme to the central Pacific. Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands was used for atmospheric explosions from 1946 with scant regard for the indigenous population.

In 1954, the Castle Bravo test exploded a 15-megaton bomb — one thousand times more deadly than the one dropped on Hiroshima. As a result, the population of Rongelap were exposed to 200 roentgens of radiation, considered life-threatening without medical intervention. And it was.

Total US tests equaled more than 7000 Hiroshimas. The Clinton administration released the aptly-named Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (ACHRE), report in January 1994 in which it acknowledged:

“What followed was a program by the US government — initially the Navy and then the AEC and its successor agencies — to provide medical care for the exposed population, while at the same time trying to learn as much as possible about the long-term biological effects of radiation exposure. The dual purpose of what is now a DOE medical program has led to a view by the Marshallese that they were being used as ‘guinea pigs’ in a ‘radiation experiment’.

This impression was reinforced by the fact that the islanders were deliberately left in place and then evacuated, having been heavily radiated. Three years later they were told it was “safe to return” despite the lead scientist calling Rongelap “by far the most contaminated place in the world”.

Significant compensation paid by the US to the Marshall Islands has proven inadequate given the scale of the contamination. To some degree, the US has also used money to achieve capture of elite interest groups and secure ongoing control of the islands.

Entrusted to the US, the Marshall Islanders were treated like the civilians of Nagasaki

The US took the Marshall Islands from Japan in 1944. The only “right” it has to be there was granted by the United Nations which in 1947 established the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, to be administered by the United States.

What followed was an abuse of trust worse than rapists at a state care facility. Using the very powers entrusted to it to protect the Marshallese, the US instead used the islands as a nuclear laboratory — violating both the letter and spirit of international law.

Fellow white-dominated countries like Australia and New Zealand couldn’t have cared less and let the indigenous people be irradiated for decades.

The betrayal of trust by the US was comprehensive and remains so to this day:

Under Article 76 of the UN Charter, all trusteeship agreements carried obligations. The administering power was required to:

- Promote the political, economic, social, and educational advancement of the people

- Protect the rights and well-being of the inhabitants

- Help them advance toward self-government or independence.

Under Article VI, the United States solemnly pledged to “Protect the inhabitants against the loss of their lands and resources.” Very similar to sentiments in New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi. Within a few years the Americans were exploding the biggest nuclear bombs in history over the islands.

Within a year of the US assuming trusteeship of the islands, another pillar of international law came into effect: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) — which affirms the inherent dignity and equal rights of all humans. Exposing colonised peoples to extreme radiation for weapons testing is a racist affront to this.

America has a long history of making treaties and fine speeches and then exploiting indigenous peoples. Last year, I had the sobering experience of reading American military historian Peter Cozzens’ The Earth is Weeping, a history of the “Indian wars” for the American West.

The past is not dead: the Marshall Islands are a hive of bases, laboratories and missile testing; Americans are also incredibly busy attacking the population in Gaza today.

Eyes of Fire – the last voyage of the Rainbow Warrior

Had the French not sunk the Rainbow Warrior after it reached Auckland from the Rongelap evacuation, it would have led a flotilla to protest nuclear testing at Moruroa in French Polynesia. So the bookends of this article are the abuse of defenceless people in the charge of one nuclear power — the US — and the abuse of New Zealand and the peoples of French Polynesia by another nuclear power — France.

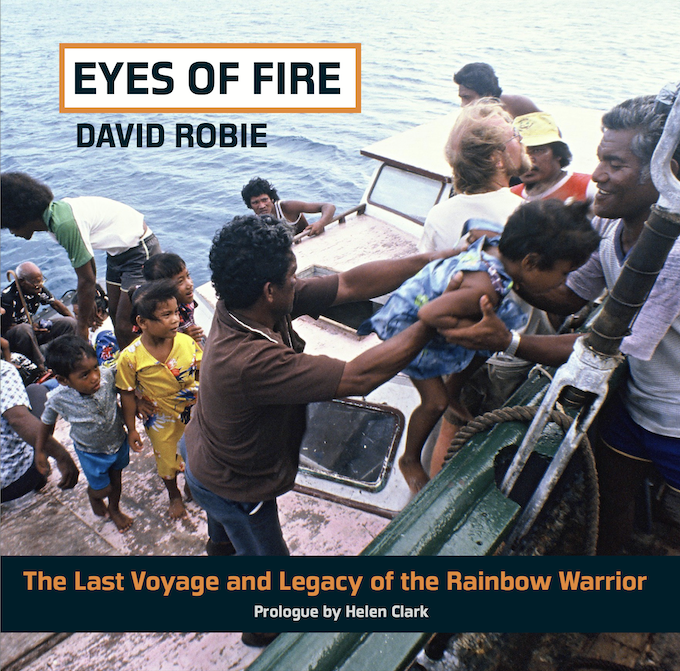

This incredible story, and much more, is the subject of David Robie’s outstanding book Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage and Legacy of the Rainbow Warrior, published by Little Island Press, which has been relaunched to mark the 40th anniversary of the French terrorist attack.

A new prologue by former prime minister Helen Clark and a preface by Greenpeace’s Bunny McDiarmid, along with an extensive postscript which bring us up to the present day, underline why the past is not dead; it’s with us right now.

Between them, France and the US have exploded more than 300 nuclear bombs in the Pacific. Few people are told this; few people know this.

Today, a matrix of issues combine — the ongoing effects of nuclear contamination, sea rise imperilling Pacific nations, colonialism still posing immense challenges to people in the Marshall Islands, Kanaky New Caledonia and in many parts of our region.

Unsung heroes

Our media never ceases to share the pronouncements of European leaders and news from the US and Europe but the leaders and issues of the Pacific are seldom heard. The heroes of the antinuclear movement should be household names in Australia and New Zealand.

Vanuatu’s great leader Father Walter Lini; Oscar Temaru, Mayor, later President of French Polynesia; Senator Jeton Anjain, Darlene Keju-Johnson and so many others.

Do we know them? Have we heard their voices?

Jobod Silk, climate activist, said in a speech welcoming the Rainbow Warrior III to Majuro earlier this year: “Our crusade for nuclear justice intertwines with our fight against the tides.”

Former Tuvalu PM Enele Sapoaga castigated Australia for the AUKUS submarine deal which he said “was crafted in secret by former Prime Minister Scott Morrison with no public discussion.”

He challenged the bigger regional powers, particularly Australia and New Zealand, to remember that the existential threat faced by Pacific nations comes first from climate change, and reminded New Zealanders of the commitment to keeping the South Pacific nuclear-free.

Hinamoeura Cross, a Tahitian anti-nuclear activist and politician, said in a 2019 UN speech: “Today, the damage is done. My people are sick. For 30 years we were the mice in France’s laboratory.”

Until we learn their stories and know their names as well as we know those of Marco Rubio or Keir Starmer, we will remain strangers in our own lands.

The Pacific owes them, along with the people of Greenpeace, a huge debt. They put their bodies on the line to stop the aggressors. Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira, killed by the French in 1985, was just one of many victims, one of many heroes.

A great way to honour the sacrifice of those who stood up for justice, who stood for peace and a nuclear-free Pacific, and who honoured our own national identity would be to buy David Robie’s excellent book.

You cannot sink a rainbow.

Eugene Doyle is a writer based in Wellington. He has written extensively on the Middle East, as well as peace and security issues in the Asia Pacific region. He contributes to Asia Pacific Report and Café Pacific, and hosts the public policy platform solidarity.co.nz