ANALYSIS: By Professor Steven Ratuva

The highly anticipated 2022 election last month was a very close, emotionally charged and highly controversial affair.

All that is behind us now and it is time to reflect on it critically and learn some important lessons as we welcome the dawn of 2023.

Despite the Supervisor of Elections’ prediction of a low percentage turnout of around the 50s, the actual turnout of 68.29 percent was surprisingly reasonable given the inconvenient December 14 date and other restrictions such as married women being required to change their names to the birth certificate ones, voting restrictions to one polling station and other legislative and logistical issues.

- READ MORE: Aiyaz ousted as Fiji MP over taking public office, rules Speaker

- Fiji’s PM Rabuka hits back: ‘We’ve every right to appoint and disappoint’

- Fiji’s draconian media law to be repealed for ‘free society’, says Gavoka

- 2022 Pacific political upheavals eclipse Tongan volcano

- Other Fiji reports

The postal ballot votes had the highest turnout rate of 75.92 per cent and the others in descending order were: Northern Division (73.88 per cent); Eastern Division (69.98 per cent); Western Division (68.82 per cent); and Central Division (65.6 per cent).

Victim of own PR system

This may sound ridiculous but it all came down to 658 voters, the equivalent of 0.14 percent of the votes, which enabled Sodelpa to stay above the 5 percent threshold.

It was this small number of voters who made the difference by giving Sodelpa the ultimate power broker position which enabled the People’s Alliance Party (PA)-National Federation Party (NFP) coalition to edge out the FijiFirst party (FFP) by a very slim margin after hours of horse trading followed by two rounds of voting.

However, this is what the voting calculus is all about — every vote counts and even one vote can make a substantial difference.

This is even more so in our Proportional Representation (PR) system, which was originally meant to encourage small parties to gain votes and be competitive against the dominant ones when it was first conceived in Europe in the early 1900s.

Theoretically, the idea is to shift the centre of power gravity from dominant parties to diverse groups to ensure that representation was more dispersed and democratic.

Thus, most countries with PR systems (there are different variants) have coalition governments.

New Zealand, which has two electoral systems merged into one (Mixed Member Proportional or MMP), consisting of the PR and First-Past-the-Post (FPP), has a history of coalitions since the PR component was introduced.

Other countries with coalition governments

Other countries which use the PR system are Israel, Columbia, Finland, Latvia, Sweden, Nepal and Netherlands, to name a few, and they all have coalition governments.

But why didn’t this coalition electoral outcome happen in Fiji during the first two elections in 2014 and 2018 although these were held under the PR system?

The reason is because the FFP was able to effectively deploy what political scientists refer to as the “coattail effect” — the tactic of using a popular political leader to attract votes.

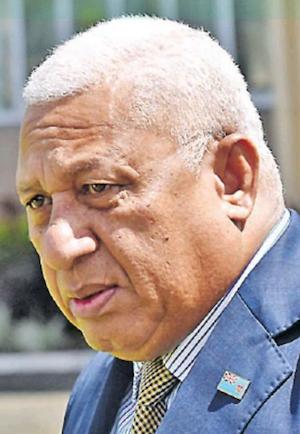

So in this case, statistics show that there has been a direct correlation between coattail votes for Voreqe Bainimarama, the FFP leader, and the electoral fortunes of the FFP.

For instance, Bainimarama was able to attract 40.79 percent of the total votes during the 2014 election and this enabled FFP to secure around 59.17 percent of the total national votes. Bainimarama’s votes went down to 36.92 percent during the 2018 election and this reduced the FFP voting proportion by 9.12 percent to 50.02 percent.

The decline in Bainimarama’s votes to 29.08 percent during the 2022 election also reduced the FFP’s votes to 42.55 percent, well below the 50 plus 1 mark needed by the party to remain in power.

The total decline of 11.71 percent of Bainimarama’s votes and 16.62 percent of the FFP votes between 2014 and 2022 is a worrying sign and if the trend continues, they may be hitting the 30 percent mark at the time of the 2026 election.

By and large, the swing of votes away from FFP was around 10 percent or so, with a shifting margin of around 3 to 4 percent.

The long Bainimarama coattail has slowly withered away over time.

Before the election I warned in a Fiji Times interview early in 2022 that given the diminishing trend of the FFP electoral support, together with other data, the party would be lucky to survive the 2022 election and thus would need a coalition partner.

I also said that the PA, NFP, Sodelpa and other parties would need to form a national coalition to be able to rule.

The writing was on the wall and it appeared that the FFP was going to be victim of the PR electoral system they introduced in an ironically Frankensteinian way.

“Wasted votes” and weakness of the PR system

The results of the 2022 election shows that the power gravity has shifted significantly and in future we are going to see governments in Fiji formed on the basis of coalitions and thus elections will need to be fought on the basis of party partnership.

This means that smaller parties, which have no hope of getting over the 5 percent threshold will need to make critical assessments and the only survival option is to join bigger parties which have more chances of winning.

Herein lies one of the weaknesses of our version of the PR system where the votes by the smaller parties, which cannot get over the 5 percent threshold, are considered “wasted”.

This is in contrast to the Alternative Voting (AV) system under the 1997 Fiji Constitution, which provided for losing votes to be recycled and used by other parties based on preferential listing. In the 2022 election, 35,755 votes were “wasted”, which equated to 4.81 percent of the total votes.

By Fiji standard, this was a relatively large number indeed.

However, the idea of “wasted votes” is a contentious one because, while from an electoral calculus point of view, these votes may serve no purpose and are deemed useless, from a political rights perspective, the votes represent people’s inalienable moral and democratic rights to make political choices, whatever the outcome, and thus must be respected and not condemned as wasted.

The new era of transformation

The small margin of 29 to 26 seats and indeed the intriguing 28-27 voting in Parliament should be reason for the Coalition government to be on its toes and not be complacent about the sustainability of the three-party partnership.

They must try as much as possible to maintain a united synergy through a win-win power sharing arrangement.

They have started this so far with the co-deputy prime ministership and portfolio sharing and this needs to deepen to other areas so that it is not seen as a marriage of convenience but a genuine attempt at nation building and transformation.

To keep their momentum going and mobilise more support and legitimacy, they need to use the diverse expertise and wide range of professional skills at their disposal to bring about meaningful, consultative, transparent and transformative policy changes for the country.

Part of the process will be to reverse some of the FFP’s fear-mongering, vindictive, controlling and authoritarian style of policymaking and leadership, which have left many victims strewn across our national landscape and which weakened support for the FFP.

While there are still flames of anger and vengeance burning in some people’s hearts as a result of victimisation by the previous regime, it is imperative now to listen to Nelson Mandela’s advice after he was released from jail — allow the mind to rule over emotions and move on with dignity.

We must break the cycle of political vengeance and vindictiveness, which became part of our political culture since 2006 and as prominent lawyers Imrana Jalal and Graham Leung have advised, it is important to ensure that changes are within the law and not driven by destructive emotions, or else we will be following the same path as the previous regime.

These will take a high degree of levelheadedness and moral restraint, qualities already displayed by the coalition leadership so far.

For the FFP, it is time to go back to the drawing board, rethink about their overreliance on coattail approach, re-strategise and reflect on why voters are deserting them.

They will no doubt be sharpening their daggers to get inside the coalition armour and target the weak links and vulnerable spots.

They will try all the tricks in the book to make the coalition partnership as shortlived as possible through destabilisation strategies and vote poaching by winning over an extra Sodelpa vote to add to the single mysterious vote, which went FFP way during the parliamentary vote for the Speaker and PM.

Sodelpa may need to warn the person concerned and if the betrayal does not stop after the next round of parliamentary vote then they may need to invoke Section 63(h) of the Constitution, which specifies that a parliamentarian can lose his or her seat if the person’s vote is “contrary to any direction issued by the political party…”

This will then open the door for Ro Temumu Kepa, who is next on the SODELPA party list, to take the vacant seat and help stabilise the coalition’s parliamentary position a bit more.

Some electoral lessons for the future

The intense political horse-trading, high pressure power manoeuvring and stressful competition for coalition partnership in the hours after the election has taught us a few lessons.

Firstly, political parties should now start thinking about forging partnerships because future elections can only be won through coalition.

PAP and NFP made a great move by getting into a coalition early and this worked out well for them.

The coalition government now has a head start.

Secondly, political parties should learn to be humble, not burn their bridges when they part with their old comrades nor should they feel super and invincible by trying to do things on their own. Old grievances can come back to haunt you if they are not addressed early

Thirdly, small parties need to pay attention to the electoral calculus and engage with parties, which have potential to propel them above the 5 percent threshold or join together as small parties to form larger political groupings before the election.

Fourth, voters will need to be smart and strategic about their votes to ensure that they are not wasted.

These “wasted” votes do make a difference in the end when the results are tallied.

Fifthly, given the need for partnerships, especially when margins are narrow, forging positive relationship and goodwill with other political parties early before elections can be rewarding political capital while vindictiveness and ill will can be destructive and regrettable political liabilities.

There is still time — about 48 months away before the next election.

Steven Ratuva is distinguished professor and pro-vice chancellor Pacific at the University of Canterbury and chair of the International Political Science Association Research Committee on climate security and planetary politics. This article was first published in The Fiji Times and is republished with permission.