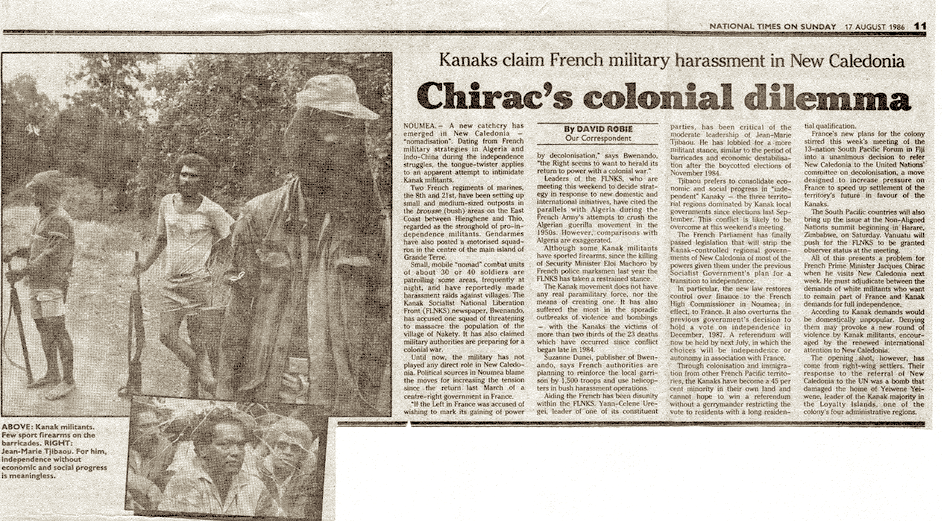

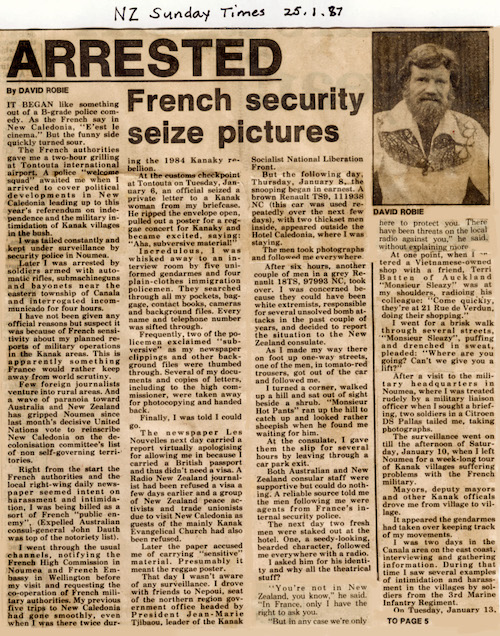

French police and soldiers harassed and arrested Islands Business correspondent David Robie during an assignment in New Caledonia in January 1987. It was his sixth visit there. This was his report in the February 1987 edition of IB.

SPECIAL REPORT: By David Robie

It began like something out of a B-grade police comedy. As the French say in New Caledonia, c’est le cinema. But the funny side quickly turned sour.

At first, the French authorities gave me a two-hour grilling at Tontouta international airport. A police “welcome squad” awaited me at the arrival lounge when I flew in to cover political developments in the South Pacific territory leading up to this year’s [1987] referendum on independence and the military “nomadisation” of Kanak villages in the brousse (bush).

Then I was tailed constantly and kept under surveillance by security police in Nouméa.later, I was actually “arrested” by soldiers armed with automatic rifles, submachineguns and bayonets near the eastern township of Canala and interrogated incommunicado for four hours.

I have been given no official answers about why, but I suspect it was because of French sensitivity about my planned reports of military operations in the Kanak areas of New Caledonia. This is apparently something France would rather keep away from world scrutiny.

Few foreign journalists venture into rural areas of Kanaky New Caledonia. And a wave of paranoia towards Australia and New Zealand has gripped Nouméa since the decisive United Nations vote to reinscribe New Caledonia on its Decolonisation Committee’s list of non self-governing countries.

From the start, the French authorities and the local rightwing daily newspaper seemed intent on harassment and intimidation. I was being billed as a sport of French “public enemy”. (Expelled Australian Consul-General John Dauth was top of the notoriety list!)

I went through the usual channels: notifying the French High Commission in Nouméa and French Embassy in Wellington well in advance of my visit and requesting the cooperation of French authorities (to enable my interviews). My previous five trips to New Caledonia had gone smoothly, even when I was there twice during the 1984 Kanak rebellion.

At the Customs checkpoint at Tontouta on Tuesday, 6 January [1987], an official seized a private letter to a Kanak woman working for a government office out of my briefcase. He ripped open the envelope and pulled out a poster for a reggae concert for Kanaky and became excited, saying: “Aha, subversive material!”

Incredulous, I was whisked away to an interview room by two uniformed gendarmes and four plainclothes immigration policemen. They searched through all my pockets, baggage, contact books, cameras and background files. Every name and telephone number was sifted through.

Frequently, two of the policemen exclaimed “subversive” as my newspaper clippings and other background files were thumbed through. Several of my documents and copies of letters , including to the High Commissioner, were taken away for photocopying and handed back. Finally, I was told I could go.

The daily newspaper, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, next day carried a report virtually apologising for allowing me in because I carried a British passport and thus did not need a visa. A Radio New Zealand journalist had been refused a visa a few days earlier and a group of 38 New Zealand trade unionists, church activists and peace campaigners due to visit New Caledonia as guests of the mainly Kanak Evangelical Church had also been refused visas.

Later, the newspaper accused me of carrying “sensitive” material. Presumably it meant the reggae poster.

That day I wasn’t aware of any surveillance — I drove with friends to Nepoui, seat of the Northern Region government office headed by President Jean-Marie Tjibaou, leader of the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS). After that I noticed a car with two men inside parking outside the budget Hotel Caledonia, where I was staying. They took photographs and followed me everywhere.

After six hours, another couple of men in a light brown Renault 9TS, 111928NC (this car was used repeatedly over the next few days), took over, I was concerned because they could have been white extremists, responsible for several unsolved bomb attacks in the past couple of years, and decided to report the situation to the New Zealand Consulate.

As I made my way to the Consulate on foot along one-way streets, one of the men, in tomato-red trousers, got out of the car and followed me. I turned a corner, walked up a hill and sat out of sight beside a shrub. My follower came running up the hill to catch up. he looked rather sheepish when he found me waiting for him.

At the Consulate, I gave them the slip for several hours by leaving through a carpark exit. Both Australian and New Zealand consular staff were supportive but could do nothing. A reliable source informed me that the men following me were agents of the DST, France’s internal security agency.

The next day two fresh men were staked out at the hotel. One, a seedy-looking, bearded character who claimed to be Spanish-born, followed me everywhere with a radio. I asked him for his identity and why all the theatrical stuff?

“You’re not in New Zealand, you know,” he answered. “In France, only I have the right to ask you. But in any case, we are only here to protect you. There have been threats on the local radio against you.” He wouldn’t explain further.

At one point, when I entered a Vietnamese-owned shop with a friend, Terri Batten of Auckland, my watcher was at my shoulder, radioing is colleague: “Come quickly, they’re at 21 Rue de Verdun, doing their shopping. “I went for a brisk walk through several streets. My watcher, puffing and drenched in sweat, pleaded: “Where are you going? Can’t we give you a lift.”

After a visit to the military headquarters in Nouméa where I was treated rudely by a mlitary liaison officer when I sought a briefing, two soldiers in a Citroën DS Pallas tailed me, taking photographs. The surveillance went on, until the afternoon of Saturday, January 10 [1987], when I left Nouméa for a week-long tour of Kanak villages suffering problems with the French military. Mayors, deputy mayors and other Kanak officials drove me from village to village. It appeared the gendarmes had taken over keeping track of my movements.

I was two days in the Canala area on the East Coast, interviewing and gathering information. During that time I saw several examples of intimidation and harassment of villagers by soldiers from the 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment.

On Tuesday, January 13, Terry Batten and I left for Tuoho in a Central Region government car driven by a senior FLNKS official, Edmond Kawa. I decided to take several photographs of the two military outposts on the outskirts of Canala village — something which had already been done and reported on by French journalists, and which is perfectly legal.

As we drove slowly past the bamboo-and-barbed wire enclosure at Negropo, I shot a few photographs from the car window without stopping. By the time that we arrived at the second post, four kilometres down the road, a squad of 10 soldiers had blockaded the road and were fixing bayonets to their automatic weapons. A couple of soldiers crouched in the bush, pointing their guns at us.

A jeep screeched to a halt and a captain peered into the car: “Monsieur Robie? Are you David Robie, the New Zealand journalist?” he asked.

When I replied yes, he said the gendarmes were “on their way”. Our passports were confiscated and we were escorted to the Canala police station.

The deputy commander of the station — he refused to give his name — accused me of taking “unauthorised” photographs of military installations, loosely using the word “espionage”. He dismissed by argument that a temporary military post on a public road through a village was not a “military base” and that I had a democratic right to take such photos.

I was detained at the station for four hours and was refused the right to phone the New Zealand Consulate, or anybody else. Nor was Terri Batten allowed to leave or contact anybody. I was also refused the right to have an interpreter (for the legal complexities of the situation we were in).

Although calm, at one point I snapped: “Is this a democracy?”

“No, this is France . . .,” the officer fired back.

“No, no . . . this is Kanaky,” interrupted Kawa. The gendarme gave him a warning.

The deputy commander tried to make me sign a statement in French which differed from the facts. He would not fully explain my four-hour detention.

I refused to sign the French statement, instead signing my own one that I wrote in English. A roll of my photographic negative film was confiscated. However, it was the wrong one (I had earlier switched cameras) — it merely contained two photographs, one of a coconut palm and the other of a mango tree. Then I was freed.

The surveillance and harassment continued until two days before leaving Nouméa, when I was summoned for an interview with General Michael Franceschi, Commander-in-Chief of French Forces in New Caledonia. He was effusive and apologetic about the “unauthorised” photography incident.

Suddenly the atmosphere changed. the agents tailing me were no longer evident. I left through Tontouta airport on January 22 without a hitch.

How bizarre. Perhaps I wasn’t really a “spy” after all.

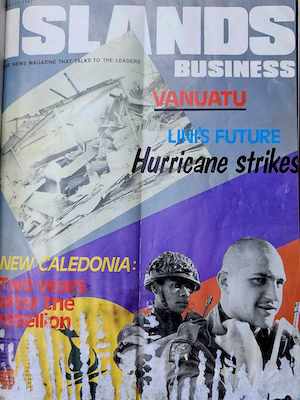

- David Robie’s full reports from this New Caledonia assignment were published as a cover story in the March 1987 issue of Islands Business.