“It’s ironic that my work is published more outside New Zealand than it is here.” (Article first published in 1992).

PROFILE: By Murray Horton

“My conception of reporting may seem somewhat unorthodox — perhaps some would say heretical. As members of human society, I believe reporters should regard their responsibilities as being contractual obligations to editors, and their own personal interests. A simple illustration: a child being beaten to a pulp by a bully. A reporter who rushes to record the scene with a camera and tape recorder might succeed as a journalist, but [they] fail as a human being. [Their] first responsibility is to rescue the child. A reporter is not an electronic computer digesting dispassionately the facts with which [they] are confronted. [They are] endowed with reason and conscience bequeathed by many centuries of human experience. [They] cannot remain coldly aloof and objective when basic human issues are involved. My concept of reporting is not just to record history, but to help shape it in the right direction.”

— Wilfred Burchett in his 1969 book Passport.

“Watch out for a fiction writer named David Robie masquerading as a journalist and an instant expert on the Philippines . . . It’s really amazing why many foreign newspapers send idiots to this country when they could have told them instead to stay in their cells in the insane asylum back home where they can merrily manufacture mad stories. . . . And to think that many of us seem to have more faith in these parasites who just fly in, eat and drink on some local sucker, bat off an analysis, then fly out.”

— Philippine Daily Inquirer column, “Idiots sent to smear us”.

“[It] was written by David Robie, a New Zealand freelance journalist who has earned himself the rare distinction among French and Tahitian government and French military officials as being one of the most unpopular Anglo-Saxon journalists working in the South Pacific.”

— Tahiti Sun Press

“Ah, David Robie. The closest thing we’ve got to a war correspondent.”

— A Christchurch Press journalist

“Who knows, Robie and Rabuka may both go down in history as putting the Pacific Islands on the political map!”

— A Massey University professor

Objectivity in journalism is a myth. Most journalists are subjective, whether they admit it or not. And most media institutions are extremely subjective. Their inherent bias is cloaked in so-called “news judgment”. In fact, objectivity is merely a euphemism for reporting from a position that reflects the status quo, and the values reported by the establishment. Any reporter who deviates from that narrow position, or is perceived as a Leftist, is branded “biased”.

“I see my role as a journalist to be even-handed, to report on issues that need to be debated as well. If there’s a can of worms within a progressive movement, then that needs to be exposed. You shouldn’t hide things under the carpet just because it happens to be Leftwing.”

- READ MORE: Blood on their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific [Open Access]

- Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific

- Other books by David Robie, including Eyes of Fire and Tu Galala

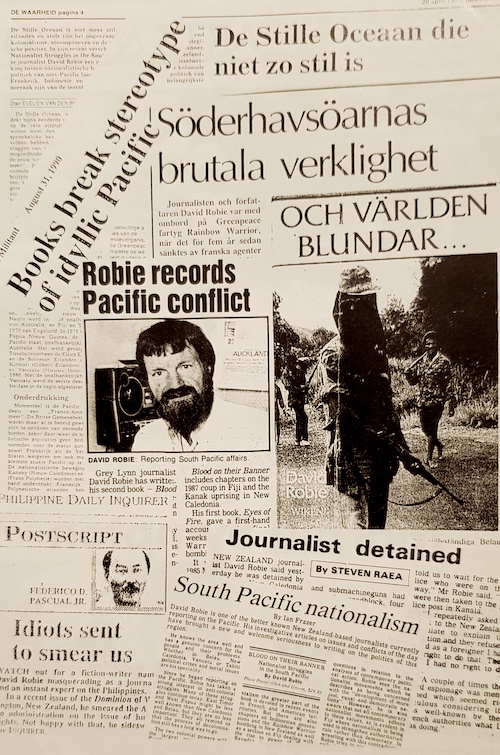

David Robie is that great rarity among the dwindling and dispirited band of gutless New Zealand journalists. He travels his beat (Asia/Pacific) regularly to see for himself; he freelances (albeit, even more tenuously); he is a progressive, whose scrupulously researched articles appear in both the mainstream media and NZ Monthly Review; and he is constantly the subject of personal controversy.

In the course of his work, Robie has been arrested at gunpoint by the French military in Kanaky New Caledonia. He was on board the Rainbow Warrior as a journalist for more than 10 weeks leading up to when it was bombed in July 1985. He hasn’t been allowed into Fiji since the 1987 coups, a fact which hampers his defamation suit against the Suva-based Islands Business magazine (for which he wrote as a chief correspondent for eight years).

His 1989 book, Blood on their Banner, had to be published in Swedish first because the prospective New Zealand publisher wanted to cut out [a chapter], specifically on East Timor, West Papua and Indonesian colonialism. He has regularly been the subject of smear campaigns and he was vilified by one section of the Māori nationalist movement and their Pākehā supporters because of his Monthly Review exposé of a clique running the Nuclear-Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) movement (“Anatomy of a hijack”, NZ Monthly Review, No 328, December 1990, pp.16-21).

“There was a feeling among a number of so-called progressive activists that I should not have written about the internal workings of an indigenous group. I regard that as a very fascist approach. Rather than discuss the issue openly, they want to shoot the messenger.”

Robie, who describes himself as “independent”, has certainly paid a high price for being the closest New Zealand journalist to John Pilger (or one of his mentors, the late great Wilfred Burchett). He lives in Auckland, working from his Grey Lynn home, which is the office for [Café Pacific media]. Launched in 1991, it operates from his converted garage. But his work rarely appears in the Auckland press. He is better known to Christchurch readers of The Press, and even there his features appear a lot less frequently than they used to. He was also for several years a regular contributor to The Listener and The Dominion.

“It’s ironic that my work is published more outside New Zealand than it is here.” Robie writes for several overseas publications, including the Pacific Islands Monthly, and his articles are syndicated to 250 newspapers worldwide by a London-based agency, Gemini News Service.

Robie is regarded as anathema by the media establishment. More than once he has been interviewed for commissioned profiles for major magazines. Not one has actually been published — “not sexy” enough was the reason one writer was given by his editor. [Later, in 2002, The Listener published a profile by Mark Revington — “Guns and money”.]

The 1990 launch of Blood on their Banner was ignored by the New Zealand media and courtesy of yours truly, the [now closed] Christchurch Star saw fit to make a major feature out of the launch speech by Race Relations Conciliator Chris Laidlaw. For the 1992 Tu Galala: Social Change in the Pacific book launch, Robie secured the telegenic former Prime Minister David Lange to make the speech. That, and not the book per se, drew the coverage.

Since the advent of the Employment Contracts Act, Robie has found freelancing the toughest it has ever been, and has been considering other challenges. He was recently shortlisted For Amnesty International’s director of media relations job in London. [Robie was later appointed head of journalism at the University of Papua New Guinea in Port Moresby.]

Even getting around his usual traps is no longer straightforward. For the most recent Pacific trip, to Papua New Guinea, he travelled as a business “consultant”, not a journalist. This is due to PNG’s official sensitivity to journalists on the Bougainville issue, one which Robie has covered firsthand.

There was nothing in Robie’s perfectly ordinary Kiwi upbringing to suggest that he would become a controversial Asia-Pacific writer. It was only as an adult that he discovered his great-great grandfather, James Robie, was a crusading journalist in Edinburgh. He edited and published the Caledonian Mercury (1860-1866), campaigning for the abolition of slavery in the United States, and against social injustice in his own country.

“It dawned on me that it was in the blood, that he wrote these 40 or 50-page political tracts.”

Robie is 47 and the oldest of three siblings. His father was a factory manager and is now retired in Pauanui. He grew up in Eastbourne, going to Wellington Boys College. He was a carnivorous youth, trapping possums for pocket money — he had to deliver sackloads of ears to the NZ Forest Service to prove his tally. He also hunted deer and goats with a bow and arrow — archery was his school sport.

He was a Queen’s Scout, representing New Zealand at a World Jamboree at Marathon Bay, Greece, when he was almost 18, and while he was abroad he spent time in France, which gave him the urge to travel.

A love of tramping compelled him to enrol in forestry at Victoria University and he spent his first year living in Kaingaroa Forest, in the central North Island. While there he rethought his direction in life, realising that he had enjoyed writing at school — “and was very good at it”.

During his second year at Victoria, he also worked for the Forest Service publications division. After leaving university, he started as a trainee journalist on The Dominion.

It was strictly a job at that stage. “I had a very apolitical background, my political awakening came later.” Motivated by a personal friendship with the son of NZ’s then military chief-of-staff, whose father was later ambassador to South Vietnam, Robie later volunteered for the Army with the view of going to Vietnam for adventure. “I came to my senses” before signing up.

In 1966, he left The Dominion as a subeditor and moved to Auckland as assistant editor of the AA magazine, Auto Age, and then moved on to become a subeditor on The New Zealand Herald. “I worked there for eight months, and it was the worst paper I’ve ever worked for. It was, and is, so incredibly conservative.”

In 1968, he married his first wife, Penelope. That year they moved to Australia for the big OE and ended up staying overseas for 10 years. He started as a sub/reporter on the Melbourne Herald. “I was there at the end of its increasing circulation period, then it started to lose to TV, as virtually all afternoon paper have.”

He saw an advert for “crusading and fearless journos” to join a new newspaper, and moved to the Melbourne Sunday Observer as chief subeditor. Published by the transport magnate Gordon Barton, this was the first major newspaper in Australia to use colour, and the first to be strong on social justice issues.

In 1970, at 24, he became the youngest metropolitan editor in Australia. However, like NZ and the US, that country was being torn apart by the Vietnam War and conscription. He wrote editorials urging liable Australian young men to burn their draft cards. He was prosecuted for publishing the internationally infamous and gut-wrenching series of photos of the My Lai massacre. The actual charge was astonishing: “Obscenity.” It never came to anything, nor did any of the various libel claims.

One of the Sunday Observer’s principal foreign correspondents was Wilfred Burchett, the Australian journalist who beat the US blockade and travelled to Hiroshima to reveal the horror of the nuclear devastation to the world. Because the 1949-72 Liberal/Country government deemed Burchett a communist, his Australian passport was stolen from him, reputedly by the CIA. When his father died, the Australian government still refused him a passport.

The Observer flew Burchett in to Brisbane from Noumea on a chartered plane. Once in the country of his citizenship, the authorities were powerless, as Burchett had committed no crime — literally, the first act of the Whitlam Labor government was to issue him a passport.

Managerial gutlessness soon got rid of editor David Robie. Several editorial staff were dismissed (mainly photographers for “using too much film”), and he was fired by the managing director for allowing the use of the word “frigging” in the regular political carton strip. He secured an out of court settlement to ensure his contract was paid in full. That was the end of Australia for him — today there are no crusading newspapers there, the last being The National Times; no Western country has a more vertically integrated media ownership structure.

He and Penelope moved to South Africa where he became the chief subeditor and night editor at Johannesburg’s Rand Daily Mail: “My approach to journalism was very much shaped by editors like Laurence Gandar, Raymond Louw and Alister Sparks.”

In contrast to NZ media, both the Sunday Observer and the Mail were non-establishment newspapers. The latter was an outspoken anti-apartheid paper. It was the conscience of the white community and some of its senior journalists had been jailed for simply doing their job. It has since gone out of business [1985] because it was perceived to be increasingly read by blacks and then its advertising revenue collapsed.

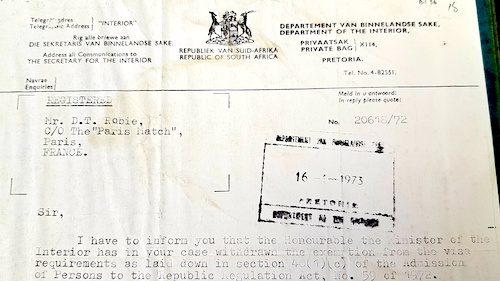

Robie could only take two years of apartheid South Africa and had to leave for the “sake of his sanity”. “It’s an utterly abhorrent system.” They refused to have servants: “I was known among the more reactionary journalists as the ‘pinko from New Zealand’.” He tackled the notorious apartheid laws on quoting “banned” people, and publishing “banned” photos, such as ones of racially mixed couples.

“I won’t go back to South Africa until there is majority rule.” After he left, he was declared persona non grata in early 1975 — curiously enough the papers, from Interior Minister Theo Gerdener, were delivered addressed to him “c/o The ‘Paris Match'” magazine via the British diplomatic bag in Nairobi, Kenya, when he was living there. Just to prove that he was as unwelcome in black dictatorships, he was also declared persona non grata in Zaire.

After six months travelling overland in Africa, they ended up in Ethiopia where he spent a year as group features editor on the Nairobi Daily Nation, the Aga Khan’s anti-colonial newspaper. “I had the shock of coming from South Africa, where some media tackled the government, to an independent country where the media basically did not buck the system.”

A senior journalist was abducted and detained by the GSU special police for being about to expose a pharmaceutical scandal. The paper did not campaign for his release, but went cap in hand to the government.

After Kenya, they spent a further six months travelling in Africa. Robie bought a rubber stamp kit, issuing his own vehicle registration papers and his own visa for Zaire. [This was necessary to remove any evidence of them having been in South Africa]. They travelled through Idi Amin’s Uganda, central and western Africa, across the Sahara Desert to Algeria, then through Spain to France, freelancing as they went.

From 1975-77, Robie was a desk editor and foreign correspondent for Agence France-Presse news agency, based in Paris. He covered the African boycott of the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal, Canada, and had a brief career as a sports writer, including covering rugby internationals at the Parc des Princes in Paris, and in Toulouse.

“In many respects I found working in Paris enormously stimulating. I started becoming intensely interested in French neocolonialism in the Pacific.”

Previously Robie had been a typical Eurocentric Kiwi. The Kirk Labour government taking French nuclear testing to the World Court was a big story, and Robie covered Greenpeace founder David McTaggart’s “piracy” case against the French military. Robie was also writing for the now defunct Nation Review, in Australia — and he wants it known that he has occasionally written for rightwing magazines, including To The Point, published in Brussels and later exposed as being financed by the South African Muldergate slush fund.

“New Zealand international coverage generally, not just the Pacific, is abysmal. No daily newspaper has a proper foreign editor with any proper resources.”

In 1978, he and his former wife returned to Auckland for family reasons. “I hated coming back, it took about two years to adjust to the parochial mentality.” He was foreign news editor of the Auckland Star until 1981.

“At the time it was probably New Zealand’s best newspaper, certainly the most liberal. I had a personal frustration, I wanted more Pacific and international coverage of our own. I was writing on the Pacific; I found myself in the ridiculous situation of using my holidays to travel the Pacific and sell the stories to the Star. I decided to leave and work freelance.”

Robie covered the 1981 Springbok rugby tour protests for the London Sunday Times. He was on the ground at Hamilton, where invading protesters forced the cancellation of the game, with the crowd baying: “Let’s get the journalists — they started it all.”

He freelanced on Pacific and development issues until 1983. Indeed, his first book had the unexciting title “United Nations Development Programme in the South Pacific”. Then he edited Insight, the magazine for American Express cardholders. It rapidly became the same old story — management didn’t like its punchy style, the Bob Jones columns, or the Brockie cartoons.

“They were just gutless, the general managers were abysmal.” The publishing company lost the contract, so he became redundant as editor and his final cover story on the “owners of New Zealand” was censored because it was too “controversial”. [The cover story was later published in another magazine, New Outlook]. It was the last time he worked for a boss.

Since 1985, David Robie has been an Asia-Pacific affairs independent journalist, and for a time he was associate editor of New Outlook magazine. “I write a diverse range of artices, depending on the publications. You wouldn’t condemn a rugby writer for not writing about golf.”

He spent almost 11 weeks on the Rainbow Warrior’s final voyage in 1985. He was the only journalist out of six on board. His 1986 book, Eyes Of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior concentrates on the actual voyage and the evacuation of the Rongelap nuclear test victims, rather than the bombing of the Warrior in Auckland harbour on July 10. [Although that is covered strongly too – the book was reviewed by CAFCA Watchdog’s reviewer, the late Jeremy Agar here].

“It wasn’t a Greenpeace manifesto; indeed Greenpeace would be quite embarrassed by some of its contents. It’s typical of the shallowness of the NZ media that they weren’t interested in the Rongelap evacuation. Any suggestion that Fernando Pereira’s death was a tragic accident is an obscene lie — it was a miracle that at least people weren’t killed.” An American environmental film, based partly on the book, is still in the offing.

“New Zealand international coverage generally, not just the Pacific, is abysmal. No daily newspaper has a proper foreign editor with any proper resources. It’s almost impossible to get a New Zealand perspective on events happening outside NZ. This is in contrast to Australia. It’s partly to do with the lack of competition, but it also reflects the traditional parochialism of NZ society. For the NZ media, the Pacific begins and ends with the Cook islands, Fiji, Samoa, Tokelau and Tonga — and even then the coverage is spasmodic and reacts to things like cyclones.

“The political and economic powerhouse is Papua New Guinea, but there is no coverage. Even the Bougainville struggle gets only spasmodic coverage. New Caledonia, Solomon islands and Vanuatu get only spasmodic and distorted coverage, for example the Matignon Accords (in New Caledonia), are being perceived as being highly successful and there is no coverage of the enormous opposition to them.

“There was a recent delegation of NZ journalists there, with no previous experience of the country. They believed what they were fed by French officials and leaders of the Kanak independence movement, who were alleged to have been collaborators.

“The NZ media will only cover events outside NZ if there is a junket provided.”

As a journalist, Robie accompanied the New Zealand delegation to the 1988/89 Asia/Pacific People’s Conference on Peace and Development in the Philippines. Here he ended up marrying his Mindanao facilitator, Del Abcede, to the strains of the “Internationale”. Del was a teacher union leader and organiser at home. She was a driving force in the politicised section of NZ’s Filipino diaspora population, secretary of the Philippine migrant centre in Auckland, and is actively involved in the broader progressive movement.

Since then, Robie has been to the Philippines several times, including being the only New Zealander on a study tour by Australian journalists — he was guest editor of a special issue of Diarista, the journal of the host National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

He has had more than one series of articles on the Philippines published in New Zealand’s dailies, and he specialised in analysing NZ’s forestry aid project in Bukidnon, Mindanao. Both of his two most recent books have included Filipino content. Indeed, Blood on their Banner is the only book by a NZ writer to be published in the Philippines. Leading Filipina activist Rita Baua is one of the contributors to Tu Galala: Social Change in the Pacific.

It was Blood on their Banner’s Asia content that led to its prospective publisher wanting unacceptable cuts.

Robie’s writing on the Philippines has trodden on some very sensitive local toes. A 1989 Philippine Daily Inquirer column, entitled “Idiots sent to smear us” was written by former editor-in-chief Federico Pascual. He attacked Robie for accusing the newspaper of suppressing human rights stories — one of the Inquirer’s reporters had handed him a file of affidavits about such stories that had been censored. Robie wrote a letter to the newsaper for publication, challenging Pascual. It was never published. Neither was a further letter sent to the paper’s ombudsman (internal investigator).

A year later, Robie met Pascual by chance at the University of the Philippines when gthey were panellists together on the issue of press freedom. When Robie approached Pascual and mentioned the column, the former editor denied having written anything and then scurried away in embarrassment.

It was Blood on their Banner’s Asian content that led to the prospective NZ publisher wanting unacceptable cuts, and to the ludicrous spectacle of a book on the Pacific, by a New Zealand writer, being published first in Swedish.

Not that Robie has abandoned the Pacific. It is still his bread and butter. Although he is a freelancer, he is not a glory seeking individualist, but an active unionist. He is JAGPRO’s representative in the Pacific Journalists’ Association, and is involved in a lot of press freedom issues in the region. He was instrumental in securing industry and progressive movement opposition to the 1991 Auckland visit by Fiji’s coup leader Sitiveni Rabuka to address the conference of the Pacific Islands News Association (PINA), a conservative organisation of Pacific media bosses, journalists and officials.

Above all else, David Robie is an extremely good writer and he has the bits of paper and trophies to prove it — ranging from the NZ Media Peace Prize in 1985 to the Qantas Best Feature Writer Award in 1989. His articles cover our own backyard, an area shamefully neglected by the media here. His stories are rooted in his own first hand observations.

He has chosen the financially precarious path of freelancing, and he has never shied from controversy, whether with reactionary authorities and their media mouthpieces, or with apologists hiding behind “indigenousness”. As far as New Zealand journalists and writers go, he is virtually one of a kind.

One recent event illustrates my point. After attending the Auckland launch of Tu Galala with my wife, all four of us later went to Kelly Tarlton’s Underwater World. It affected us in different ways. I was a rubber-necking tourist; the Filipinas decided to cook fish; and David drew our attention to the shark turds in the tank.

Always the journalist, always in duty. And that’s what this country and region are sorely lacking — journalists who are not merely gushing admiration for the killer efficiency of the sharks in our midst, but point out that they are showering us with shit.

Murray Horton is secretary and organiser of the Campaign Against Foreign Control of Aotearoa (CAFCA) and an advocate of a range of progressive causes for more than the past five decades. This article was first published in 1992 under the title “David Robie: One of a kind” in the NZ Monthly Review which has now ceased publication. (The author’s original title was “Foreign Correspondent”). A sequel to David Robie’s Blood on their Banner book mentioned in this article was published in 2014, Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face : Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific (reviewed by Murray Horton here). It was endorsed by investigative journalist John Pilger.