President Jacques Chirac’s controversial final round of nuclear tests at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls in 1995 unleashed an unprecedented storm of international protest. And dilemmas for journalists covering the riots in Pape’ete and the junkets by French authorities. The Vanuatu government banned news reports on protests. Journalist David Robie on board the original environmental campaign ship Rainbow Warrior — bombed by French secret agents a decade ago — recalls the events. He was later arrested by the French military.

By David Robie in Uni Tavur

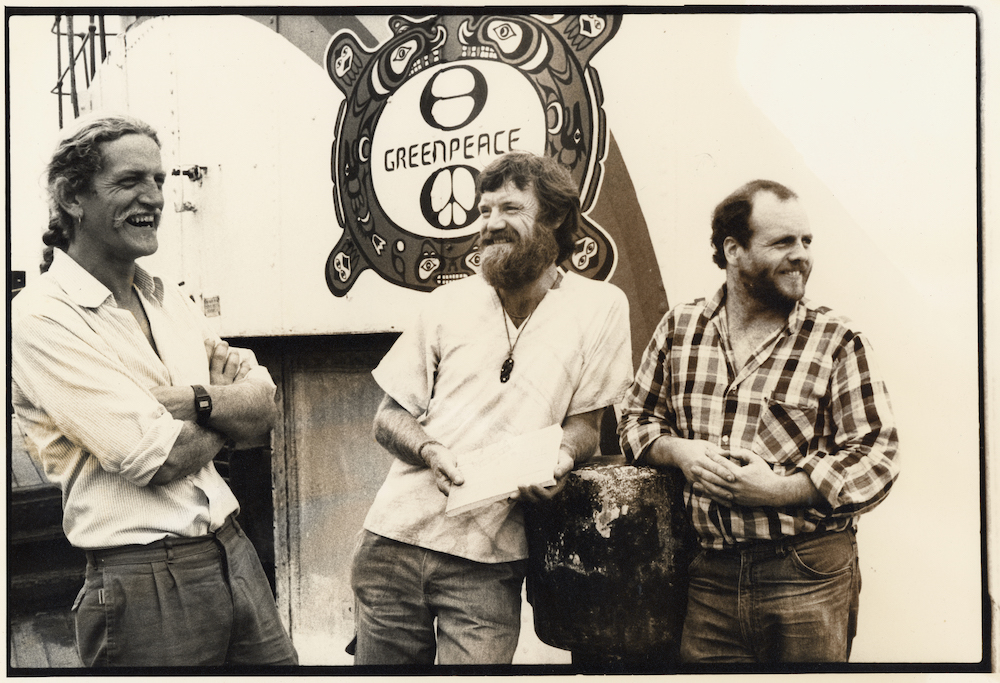

Fernando Pereira was on board the Rainbow Warrior’s ill-fated voyage to the Pacific a

decade ago almost by chance. Campaign coordinator Steve Sawyer had been seeking a wire machine for transmitting pictures from the Marshall Islands and Moruroa Atoll.

Sawyer phoned Fiona Davies, then heading the Greenpeace photo office in Paris. But he said he wanted a machine and a photographer separately.

‘No, no … I’ll get you a wire machine,’ promised Davies. ‘But you’ll have to take my

photographer with it.’ Agreed. The deal would save Greenpeace’s campaign budget about

US$8000.

But it would also cost the Portuguese-born photojournalist Pereira his life. Less than

three months later he was dead — drowned as the Rainbow Warrior, bombed by French secret service agents, sank to the bottom of Auckland Harbour.

The ship’s successor, Rainbow Warrior II, returned to French Polynesian waters in 1995 for another dramatic tilt at the French over nuclear testing. Again, American Steve Sawyer was on board for the first round of protests in July.

For thousands of people in the Pacific, the French plan to resume nuclear tests this year reopened a deep and bitter wound.

New Zealand has long played a key anti-nuclear role. Twice in 1973 it dispatched frigates to the Moruroa Atoll testing zone to protest over atmospheric tests. A World Court case filed jointly with Australia forced France to switch to underground tests the following year.

Yet, in spite of persistent small boat protests over ensuing years, it was not until a decade ago that this major act of French state terrorism in New Zealand’s largest port suddenly projected nuclear tests at Moruroa firmly into the international limelight.

Irony of the saboteurs

The night was chilly as the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior lay moored at Auckland’s

Marsden Wharf on Wednesday, 10 July 1985. It had arrived in New Zealand from Vanuatu three days earlier — a week after President Haruo Remeliik had been assassinated in Belau.

Greenpeace campaigners were preparing the former North Sea fishing trawler for the environmental group’s biggest-ever protest voyage to Moruroa Atoll, one which they hoped

would embarrass France over nuclear testing even more than the many brave forays of the yacht Vega. On board, supporters celebrated the 29th birthday of Steve Sawyer, the American co-ordinator of the Pacific Peace Voyage.

Unknown to the Greenpeace activists, two frogmen, French secret agents Jacques Camurier and Alain Tonel, had set off in an inflatable dinghy across the 2km stretch of the misty harbour from Mechanics Bay. It was ironic that the saboteurs were using a French-made Zodiac — the craft used by marine commandos to chase the Vega in 1973 (when they bludgeoned David McTaggart, Greenpeace founder in the Pacific), and later adopted by the Greenpeace “commandos of conservation” in dramatic campaigns against nuclear waste dumpers and whalers.

Camurier and Tonel crouched low into the icy breeze as they motored slowly across the harbour. It was bitterly cold, even in their waterproof jackets and wetsuits. Stowed on board the grey-and-black craft were two explosive packs wrapped in plastic, a clamp, rope, and the rest of their scuba gear — including two rebreather oxygen tanks, which did not release telltale bubbles underwater.

It was about 8.30 pm when they were close enough to switch off the little four horsepower Yamaha motor and paddle towards the Rainbow Warrior’s berth. They moored the

Zodiac to a sheltered wharf pile. So far, so good. It was just as they had rehearsed this phase of the so-called Operation Satanic at their Aspretto base in Corsica, France.

Donning their flippers, oxygen tanks and masks, Camurier and Tonel slipped into the inky water. Then they reached over the side of the inflatable to grab the bombs, the heavier of which weighed 15 kilos. They both swam underwater with the bombs, clamp and rope to the stern of the Rainbow Warrior.

Tonel attached the smaller, 10 kilo bomb to the propeller shaft; Camurier fixed the clamp on to the keel and ran out of rope to pinpoint a spot to attach the larger bomb next to the engineroom.

The hull explosive would sink the ship; the propeller mine would cripple it. Both bombs were timed to explode in just over three hours, at 11.50 pm. The explosives laid, the frogmen headed back to their hidden Zodiac. The hardest part of their mission was over.

The first blast ripped a hole the size of a garage door in the engineroom. The force of the

explosion was so powerful that a freighter on the other side of Marsden Wharf was thrown five metres sideways. As the Rainbow Warrior rapidly sank until the keel touched the harbour floor, the shocked crew scrambled on to the wharf.

But Fernando Pereira dashed down a narrow stairway to one of the stern cabins to rescue his expensive cameras. The second explosion probably stunned him and he drowned with his camera straps tangled around his legs.

I had been on board the Rainbow Warrior for 11 weeks, and my cabin was opposite Pereira’s. But I had left the ship three days earlier, on arriving in Auckland, to return to my Grey Lynn home. A planned visit to the ship that night with my two sons and their Scout troop had been cancelled at the last moment.

When the Rainbow Warrior was refloated and towed to the Devonport Naval Base dry dock, I discovered my old cabin had a huge bulge and hole where my bunk had been. My passport had been earlier recovered by navy divers from the bridge. It sank with the ship.

A daughter’s plea

Fernando had fled Portugal during the colonial wars in Angola, Mozambique and East Timor

while he was serving as a military pilot. He settled in Holland, the only country that would grant him citizenship. An amusing, engaging and likeable environmental photojournalist, he joined the Amsterdam daily newspaper De Waarheid.

Fernando’s daughter, Marelle, then aged eight, in June 1995 appealed in the French newspaper Libération to anybody who was involved in the bombing operation to tell her fully what had happened. “Now I am 18, I am an adult and I think by now I have the right to know exactly what events transpired surrounding the explosion which cost my father his life,” she wrote. She also travelled to New Zealand to interview former Prime Minister David Lange and Greenpeace campaigners who sailed on the Rainbow Warrior.

Fernando and I were among seven journalists accompanying the Greenpeace campaigners — he was also a crew member; the rest of us were independent reporters, filing for Australian, British, French, Japanese, New Zealand and Pacific news media. Our task was to travel to the Marshall Islands to report on the evacuation of the stricken islanders from Rongelap Atoll.

The Rongelap people had been contaminated by radioactive fallout, three decades earlier, in the most tragic disaster of American atmospheric tests of the 1950s — the 15-megaton Bravo H-bomb on Bikini Atoll, on 1 March 1954.

French President Jacques Chirac’s decision to resume the tests so close to the 10th anniversary of the Rainbow Warrior bombing fuelled outrage in the South Pacific, reopened a deep wound and gave New Zealanders a feeling of déja vu. France says it needs the tests to maintain its nuclear deterrent, and will only conduct eight underground tests between this September and May 1996.

Chirac claimed the tests would have “strictly no ecological consequences”.

Since 1966, France has conducted 175 atmospheric and underground tests at Moruroa and its sister atoll of Fangataufa. The Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation says the tests have left a radioactive core in the extinct undersea volcano that forms the base of the atolls.

It said that although the radioactivity was probably sealed off from the surrounding seas for the time being, there was a serious danger of leakage over the next 500-1000 years. What worries scientists is that the debris of past explosions was a half-life of at least 10,000 years. Greenpeace studies have shown radioactivity in plankton found near Moruroa, and plutonium in seawater.

But most French health tests on the residents of French Polynesia are a military secret.

A decade after the bombing, the full reasons for the French sabotage operation in New Zealand are still unclear in spite of Paris eventually admitting responsibility after the cover-up was blown. A French government-ordered official inquiry headed by leading civil servant Bernard Tricot in August 1985 was widely rejected as a whitewash. While admitting French agents were involved, it cleared the government of ordering the sabotage.

However, in September, after further revelations of French involvement, Prime Minister Laurent Fabius admitted on state television that the French secret service DGSE had indeed sunk the Rainbow Warrior, and it had been covered-up. Defence Minister Charles Hernu was forced to resign and the DGSE chief, Admiral Pierre Lacoste, was sacked.

Complicated plot

The scandal, dubbed “Underwatergate”, was a public relations disaster for France while

Greenpeace’s membership and finances soared. Thirteen secret agents — one of them infiltrating the Auckland office of Greenpeace — were used in the operation.

One DGSE agent, tough former commando Christine Cabon, alias Frederique Bonlieu, made herself at home with Greenpeace and fed information about the Moruroa plans to her Paris headquarters.

The plot by the DGSE — codenamed Operation Satanic — was complicated. A Zodiac and

Yamaha outboard motor were flown from Britain to New Caledonia. The bombs and diving equipment were obtained in Noumea and hidden on board a chartered 11-metre yacht, the Ouvéa.

Four secret agents — Chief Petty Officer Roland Verge, petty officers Gerald Andries and Jean-Michel Barcelo, and “freelance physician” Dr Xavier Maniguet — posed as tourists on a mid-winter diving voyage to New Zealand. A second team of agents flew into Auckland from London posing as Swiss tourists on their honeymoon. They were Major Alain Mafart, deputy commander of France’s Aspretto combat diving base, and Captain Dominique Prieur with the “married” name of Turenge.

Eight days before the Rainbow Warrior arrived in New Zealand on 7 July 1985, Operation

Satanic’s chief, Colonel Louis-Pierre Dillais (alias Jean-Louise Dormand), flew into Auckland

from Los Angeles. He booked into a Kingsgate Hyatt hotel room with a birds’ eye view of the environmental ship’s berth.

During the next two weeks, the Ouvéa crew played out a Jacques Tati-like farce, seducing

women and leaving obvious clues to their presence from Whangarei to Auckland. But they

eventually linked up with the Turenges, and the bombs and sabotage gear were handed over.

A third team of two divers, Camurier and Tonel, flew into Auckland a few hours before the

Rainbow Warrior arrived in Auckland from Vanuatu. Both men had false passports and claimed to be physical education instructors at Paofai Girls’ College in Pape’ete. Their task was to mine the ship.

After planting the bombs, Camurier was spotted by yachtsmen vigilantes on the lookout

for petty thieves. He was loading bags into the Turenges’ rented campervan. The car number plate, LB8945, was jotted down and two days after the Rainbow Warrior was sabotaged the fake honeymooners were detained by police on false passport charges.

Evidence points to France

Evidence quickly pointed to French responsibility for the sabotage. Police flew to Norfolk Island to question the Ouvéa crew on their return voyage to Noumea. Although they had strong suspicions, the police did not have enough evidence for arrests. By the time the police got their act together, the Ouvéa had vanished. It had apparently been scuttled in the Coral Sea and the crew (apart from Dr Maniguet, who had earlier flown through Sydney) were picked up by the nuclear-powered submarine Rubis which took them to Tahiti.

Dillais, Camurier and Tonel posed as tourists in the South Island before quietly slipping out of New Zealand two weeks later.

Meanwhile, the French government “denounced” the sabotage and strongly denied any

involvement. French press reports claimed the saboteurs were South African mercenaries, white New Caledonian anti-independence extremists or British agents — anything to divert attention away from French involvement.

The dead photographer, Pereira, was claimed to be a KGB agent and the ship was said to be carrying secret espionage equipment — claims which I found laughable after having lived on board for so long. The Turenges were charged with murder and arson but they eventually pleaded guilty to manslaughter and wilful damage.

On 22 November 1985, Chief Justice Sir Ronald Davison sentenced them to 10 years’ imprisonment.

Faced with steadily deteriorating relations with France after the Rainbow Warrior bombing and threats to the country’s trade future, the New Zealand Government sought international mediation. Then United Nations Secretary-General Javier Perez de Cuellar ruled in June 1986 that France must make a formal apology for the attack and pay $13 million in compensation in return for a three-year deportation of Mafart and Prieur to Hao Atoll, a military base in French Polynesia.

Greenpeace was warded $8 million compensation from France by the International

Arbitration Tribunal. The environmental movement finally towed the Rainbow Warrior to New Zealand’s Matauri Bay and “buried” it off Motutapere in the Cavalli Islands on 12 December 1987.

But the affair did not end there. The same day the French government told New Zealand that Mafart had a serious “stomach complaint” and repatriated him to Paris in defiance of the terms of the United Nations agreement and protests from Prime Minister Lange’s government.

Mafart was smuggled out of Tahiti as a carpenter called Serge Quillan on a fake passport on 12 December 1987 — hours before New Zealand was told he was being repatriated. Prieur was repatriated in May 1988 because she was pregnant. France ignored New Zealand’s protests over the blatant breach of the agreement.

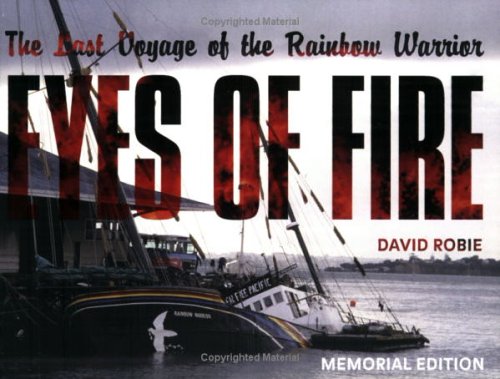

In January 1987, I was detained at gunpoint by French troops near a military outpost, while on assignment in New Caledonia. After veiled accusations of my being a “spy” and being held for several hours along with a Kanak pro-independence local government official without charge at Canala gendarmerie, we were finally released. News media reports at the time linked my arrest with intimidation over my Rainbow Warrior book Eyes of Fire and my coverage of the Kanak struggle against French rule.

The Rainbow Warrior saga still leaves a bitter taste with most New Zealanders. Although

Lange’s Labour government was revered for standing firm on its nuclear-free policy, many New Zealanders have felt disillusioned with it for backing down under trade pressure and handing over the two jailed agents to French jurisdiction.

“You cannot sink a rainbow”, claimed a slogan peddled by nuclear-free campaigners in the months after the bombing. A cliche, but it’s true.

Bibliography:

David Robie, Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior. Auckland: Lindon, 1986.

— Blood on their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific. London: Zed Books, 1989.

— (ed), Tu Galala: Social Change in the Pacific. Wellington, Bridget Williams Books, 1992.

Dr David Robie lectures in journalism with UPNG’s South Pacific Centre for Communication and Information in Development. He was one of several journalists initially on board the Rainbow Warrior, remaining with it for 11 weeks until it arrived in New Zealand. His book Eyes of Fire was the only eyewitness account. This article was adapted from Robie’s report in Uni Tavur’s Insight Report, 21 July 1995.