The Fijian crisis is not about the rights of ordinary people, says veteran Pacific affairs journalist David Robie, it is about ‘a Third World oligarchy which has failed its people’.

By Mark Revington

Sometimes power in Fiji doesn’t come from the barrel of a gun. All it takes is the threat.

During the first 10 days of the Fijian coup, some of the best reporting and analysis carne from the journalism students at the University of the South Pacific (USP), on their Pacific Journalism Online website. On the 11th day, the website was closed down.

The previous night, supporters of George Speight had trashed the studio and offices of Fiji Television, following criticism of Speight during a current-affairs show.

Pacific Journalism Online immediately posted a transcript of the programme, with its caustic criticism and political commentator Jone Dakuvula‘s observation that all the talk about indigenous rights was simply a smokescreen for a naked power grab. And vice-chancellor Esekia Solofa immediately closed it down “as a security measure” after threats were made against the university. (The website, which had been recording around 20,000 hits a day, was eventually put back in cyberspace, hosted by the journalism department of an Australian university.

Right there you had the paradox of coup-coup land (as Australian journalists have dubbed Fiji), encapsulating the two great “isms” — globalism and tribalism — sweeping the post-Cold War world, detailed by American scholar Benjamin Barber in his book Jihad v. McWorld. Look on the business pages of any paper, says Barber, and you would be convinced the world was increasingly united, that borders were increasingly porous. Look only at the front pages and you would be convinced of the opposite; that the world was increasingly riven by fratricide and civil war.

The forces driving the coup were a complex mix, including a class struggle, and a reaction against Mahendra Chaudhry‘s rollback of privatisation and its opportunities for personal power and lots of loot. Some of the businessmen said to be behind the coup, whose names are on lists circulating in Suva and by email through cyberspace, are all in favour of a free flow of capital as long as it ends up in their pockets.

Yet the coup leaders relied for their power base on an insular, tribal intolerance. It was a coup that combined primitive appeal to indigenous Fijians, with the media savvy of glib frontman Speight. And an echo of colonialism from a gun-toting band supposedly seeking to shake off the colonial shackles, (Threats and censorship are traditional weapons of heavy-handed colonial powers such as France to keep their Pacific colonies in line).

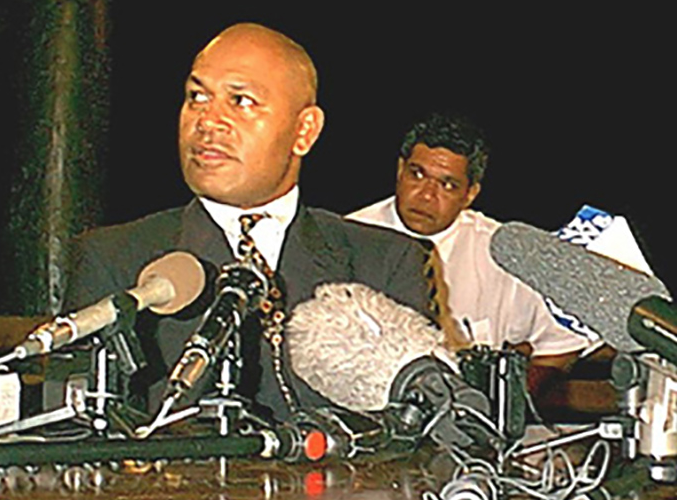

Although Speight obviously has little regard for democracy, he knows the value of a soundbite only too well, and used the media. In turn, they offered him a profile and credibility. “They fuelled the crisis and gave Speight a false idea of his importance and support,” says USP journalism coordinator David Robie.

Pulled in at the last minute as the great communicator, Speight communicated so well that there is a theory that he mounted a coup within a coup, using his new media profile to get his own way. “There is a feeling that events didn’t unfold the way some people had planned,” says Robie.

Trouble in cyberspace

Robie, who also coordinates Pacific Media Watch, a group dedicated to examining issues of ethics, censorship, and media freedom in the Pacific, had been through it before. In 1998, ministers in then Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka’s government had tried to close down Robie’s own media and politics website — Café Pacific — and revoke his work permit in what was seen as the first test of the 1997 Constitution’s freedom of expression clause. The prime mover was then Assistant Information Minister Ratu Josefa Dimuri, one of Speight’s key supporters. The politicians backed off after a two-week media controversy.

An award-winning journalist, and author if seven books, New Zealand-born Robie has been an impassioned chronicler of Pacific currents for decades, an interest developed while working as an editor and correspondent for Agence France-Presse news agency in Paris during the early 1970s. After returning to the Pacific in 1977, he began covering Pacific affairs as a freelancer.

Robie witnessed the bloody struggles for independence of the 1980s, and the attempts of independent Pacific nations to chart a nuclear-free course. He reported on the violence between France and Kanak activists in New Caledonia and the massacre of Kanak activists at Hienghène in 1984 that almost provoked a civil war. He was harassed by French secret service agents and arrested at gunpoint by the military in New Caledonia, was on board the Rainbow Warrior when it evacuated irradiated Rongelap Islanders from their atoll, leaving the ship one day before it was sunk in Auckland by French secret service agents. He was in Fiji when Labour Party leader Dr Timoci Bavadra was elected prime minister in 1987, and covered the subsequent coups.

He wrote the book Blood on their Banner, published in 1989, a detailed analysis of the struggle of indigenous people around the Pacific against the remnants of colonialism. The epilogue is just as applicable today in Fiji. “The death of democracy in Fiji was a blow to many nationalists in the South Pacific, putting the struggle of the Kanaks and other liberation movements in jeopardy,” wrote Robie, who recorded how Rabuka went on a big military spend-up, forging closer ties with France and Indonesia, the two nations so adept at using force to put down indigenous populations in their Pacific colonies.

Thirteen years on and not much seems to have changed in Fiji, says Robie.

“Chauvinistic, nationalistic struggles of this kind, based on nepotism, racism, opportunistic crime, opportunities for corruption and suppression of the human rights of others, undermine genuine indigenous struggles such as the Kanak struggle for independence from France in New Caledonia. After all, Fiji has been independent since 1970. In that time it has had indigenous governments except for one month in 1987 when Dr Bavadra was prime minister, and one year in 1999-2000 with Chaudhry.

“What have they done in all this time for the underprivileged indigenous villager? Why are they blaming the Chaudhry government after three decades of failure by Mara and Rabuka and the chiefly oligarchy? This is about a Third World oligarchy which has failed its people.”

In another one of those ironies that constantly emerge, both Dr Bavadra’s government and that of Chaudhry wanted to help Fiji’s poor, often at the expense of cosy business arrangements. Chaudhry may have been too abrasive in his political style, but his heart appeared to be in the right place. His government gave priority to genuine policies to improve health, education and social development.

“It would be fair to say that the Chaudhry government achieved more in one year than the previous Rabuka government achieved in seven years,” says Robie. “The real problem, not the racial stereotyping which Speight insisted upon, was the rollback of privatisation and an emphasis on development for the poor.”

Rabuka’s former Finance Minister Jim Ah Koy, reputedly one of the richest men in Fiji, was hellbent on privatisation in Fiji, and is one of those rumoured to be behind the coup. The rumours were so strong that Ah Koy felt compelled to make a statement, denying any complicity and launching a vicious on Chaudhry. It was run as a full page in all three daily newspapers and read out in full on Fiji Television.

Speight’s dubious business dealings have been well-documented by The Sydney Morning Herald, notably in a piece by Marian Wilkinson headlined “Mahogany Row”, which laid out in detail how Speiught, as chairman of the government-backed Fiji Pine Ltd and the Fiji Hardwood Corporation, stood to make a lot of money from the sale of mahogany forests to US interests. Chaudhry’s government questioned the price Speight was prepared to accept, and the deal, and sacked him.

Speight also appeared to have been involved in pyramid selling in Queensland, where he spent eight years as an insurance and banking broker.

Paying the price

Fiji, says Robie, is paying the price for years of failure in moral and professional leadership, and failure to develop cohesive, homegrown policies to cope with the impact of globalisation. “Years of corruption, blatant self-interest, short-term band-aid policies, and a neglect of the urdan and rural poor communities since independence have taken their toll. It is rare that politicians with vision and genuine selfless commitment to island development have emerged.”

Where to now? Anyone who knew Chaudhry would not have been taken in by his acceptance of kava and a whale’s tooth — the traditional Fiji peace offering — from his captors, says Robie. There are Australian and New Zealand judges on the bench in Fiji who are reported to be anticipating a challenge to any new government, not only on legal grounds but also on the grounds that the the coup was a violation of the constitutional rights of the Fijian people.

There is an interesting precedent, from Trinidad and Tobago, where the two main ethnic groups are descended from India and Africa. On July 27, 1990, a radical Muslim group took the Prime Minister and Parliament hostage at gunpoint, and stormed the state-run television. Their leader, Imam Yasin Abu Bakr, declared on national television that he had overthrown the government and consigned them to history. Prime Minister Arthur Robinson was shot in the foot during the six days the government was held hostage, then released to add his authority to a settlement for the release of the hostages.

As soon as they were freed, he refused to honour the agreement, saying it had been signed under duress. Over the following months the rebels were arrested and jailed.

- After being convicted of treason for leading the 2000 coup, George Speight is currently serving a sentence of life imprisonment in Fiji.

- Read more at Academia.edu

- Archive of USP student coverage of the 2000 Fiji coup

- Cass, P. (2002). Baptism of fire: How journalism students from the University of the South Pacific covered the Speight putsch and its aftermath. Round Table (London, UK), 91(366), 559-574.

- Lal, B. V., & Pretes, M. (2008). Coup: Reflections on the political Crisis in Fiji (Chapter 17, pp. 98-103). ANU Press.

- Revington, M. (2000, August 5). Guns and money. NZ Listener, 174(3143): 30-31.

[Profile of David Robie after the George Speight coup in Fiji, May 2000]. - Robie, D. (2001). Coup coup land: The press and the putsch in Fiji, Asia Pacific Media Educator, 10, 148-162.

- Robie, D., (2004). Mekim Nius: South Pacific media, politics and education. Suva: University of the South Pacific Book Centre. ISBN 9781877314308