COMMENT: By David Robie

The silence from Facebook is deafening and disturbing.

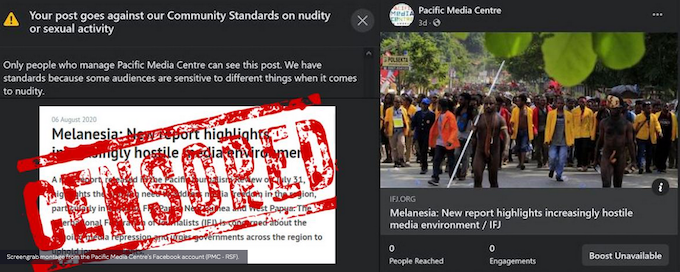

At first, when I lodged my protests earlier this month to Facebook over the immediate removal of a West Papua news item from the International Federation of Journalists shared with three social media outlets, including West Papua Media Alerts and The Pacific Newsroom, I thought it was rogue algorithms gone haywire.

The “breach of community standards” warning I also received on my FB page was unacceptable, but surely a mistake?

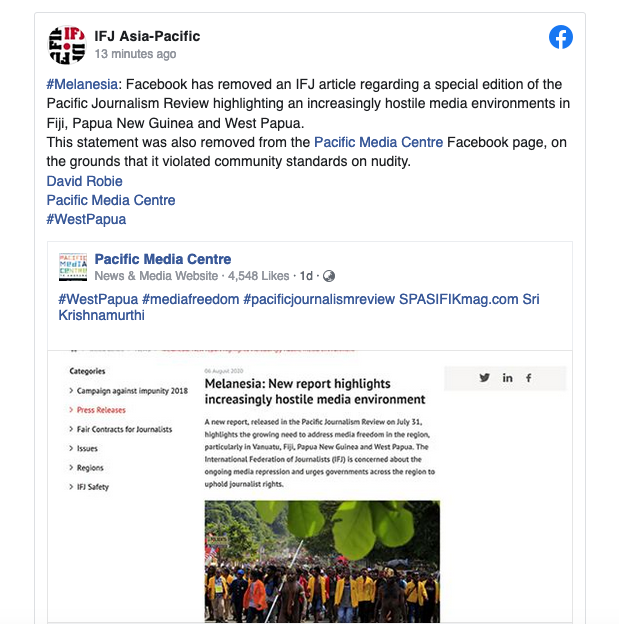

However, with subsequent protests by the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders (RSF) media freedom watchdog and the Sydney office of the Asia-Pacific branch of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the world’s largest journalist organisation with more than 600,000 members in 187 countries, falling on deaf ears, I started wondering about the political implications of this censorship.

- READ MORE: Melanesia: Facebook algorithms censor article about press freedom in West Papua

- Facebook blocks user for nudity in photos of indigenous Vanuatu ceremony

We had all complained separately to the FB director of policy for Australia and New Zealand, Mia Garlick, and were ignored.

Several news stories were also carried by Asia Pacific Report, RSF and RNZ Pacific. No reaction.

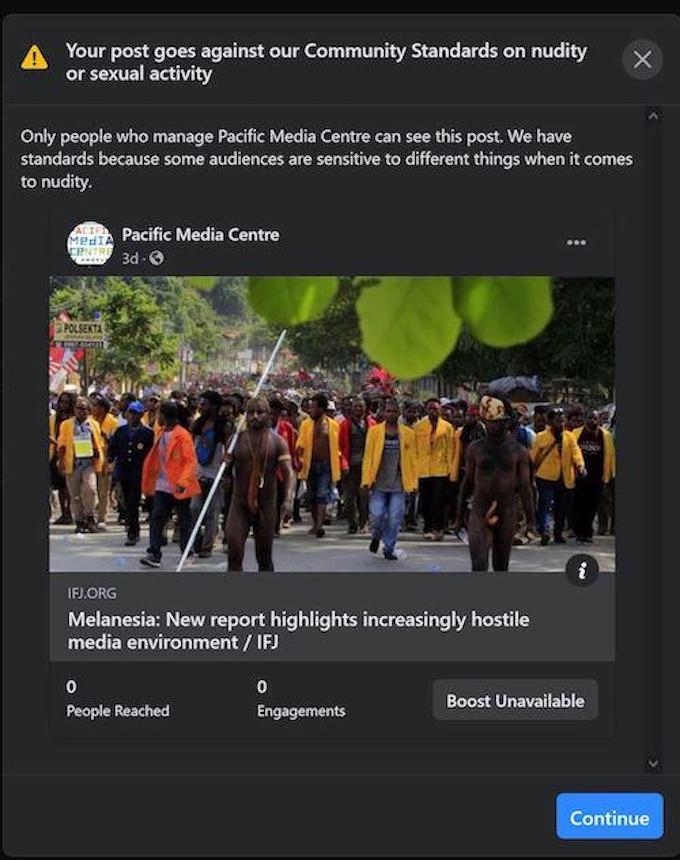

The removed item was purportedly because of “nudity” in a photograph published by IFJ of a protest in the West Papuan capital Jayapura in August last year during the Papuan Uprising against Indonesian racism and oppression that began in Surabaya, Java.

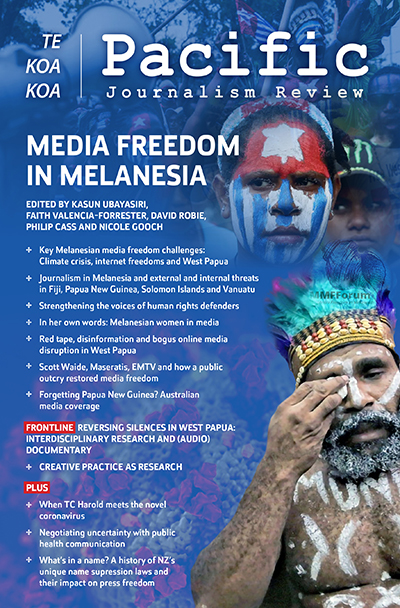

‘Media freedom in Melanesia’

The FB photo was published with an article about the content of the latest Pacific Journalism Review research journal with the theme “Media freedom in Melanesia” which highlighted “the growing need to address media freedom in the region, particularly in Vanuatu, Fiji, Papua New Guinea and West Papua”.

The two protesters in the front of the march were partially naked except for the Papuan koteka (penis gourd), as traditionally worn by males in the highlands.

As I wrote at the time when communicating with RSF:

“Anybody with common sense would see that the photograph in question was not ’nudity’ in the community standards sense of Facebook’s guidelines. This was a media freedom item and the news picture shows a student protest against racism in Jayapura on August 19, 2019.

“Two apparently naked men are wearing traditional koteka (penis gourds) as normally worn in the Papuan highlands. It is a strong cultural protest against Indonesian repression and crackdowns on media. Clearly the Facebook algorithms are arbitrary and lacking in cultural balance.

“Also, there is no proper process to challenge or appeal against such arbitrary rulings.

Using the flawed FB online system to file a challenge in this arbitrary ruling three times on August 7, I ended up with a reply that said: ‘We have fewer reviewers [to consider the appeal] available right now because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak’.”

Two letters unanswered

My two letters to Mia Garrick on August 10 and 11 went unanswered.

RSF’s Asia-Pacific director Daniel Bastard wrote to her on August 11, saying: “Since it is a press freedom issue, we plan to publish a short statement to ask for the end of this censorship. Beforehand, I’m enquiring about your view and take on this case.”

The IFJ followed up on August 14, two days after their original FB posting had also been removed, with a letter by their Asia-Pacific project manager Melanie Morrison, who described the FB the censorship as a “cruel irony”:

“As a press freedom organisation, the IFJ strongly condemns the removal of posts on spurious grounds. Such an action amounts to censorship.

“West Papua is subjected to a virtual media blackout. Access to the [Indonesian-ruled] restive province is restricted and one of the only ways to get information out is through social media.

“The photographer, Gusti Tanati, is based in West Papua and is no stranger to operating with harsh restrictions. To have his photos censored, along with an article that points to the increasingly hostile media environment in West Papua, is a cruel irony.”

Hinting at the political overtones, Morrison also noted that if Facebook was made aware of this photo by a complaint made by a Facebook user, “it is highly likely that the complainant objects to any coverage of West Papua that may be critical of the repressive situation in the province”.

She added that “understanding the background to this ongoing censorship is critical”.

Tracking truth and disinformation

Listening to journalist and forensic online researcher Benjamin Strick in an interview with RNZ’s Kim Hill last Saturday about “tracking truth” and exposing disinformation prompted me to revive this FB censorship issue.

In 2018, Strick was part of a Peabody Award-winning BBC investigative team that exposed the soldier-killers of two mothers and their children in Cameroon – The Anatomy of a Killing.

But I was alerted by his discussion of his investigation last year of the Indonesian crackdown and disinformation campaign coinciding with the Papua Uprising.

Discussing “collaborative journalism” and the West Papuan conflict with Kim Hill, he said: “The war is really online.”

He became interested in the “resurgence” or pro-independence sentiment and racial tension after incidents when some Javanese students branded West Papuans as “monkeys” and with other extreme abuse, which sparked a series of protests from Jayapura to Jakarta.

“I was investigating this thinking that it was going to be another mass human rights crime committed in West Papua,” he recalls. “But instead, when the internet was off and I was searching online, I was seeing these tourism commercials about West Papua and I was also seeing these videos on Twitter and Facebook about the great work the Indonesian government was doing for the people of West Papua.

“And they were using these hashtags #westpapuagenocide and #freewestpapua. I thought to myself this has got nothing to do with genocide, providing tourism in this context.”

‘Hashtag hijacking’

This is a process known as “hashtag hijacking”.

Strick’s research exposed hundreds of bogus sites sending our masses of scheduled “bots” – automated accounts – and were traced back to a Indonesian public relations agency InsightID linked to the government.

Recently, I was engaged with a high ranking Indonesian Foreign Affairs official, Director of the European affairs Sade Bimantara, in a webinar hosted by Tabloid Jubi journalist Victor Mambor when we talked about web-based disinformation.

However, my experience of this disinformation has been overwhelmingly linked to Indonesian trolls, and even our Pacific Media Centre Facebook page has been targeted by such attacks.

In October 2019, Strick and a colleague, Famega Syavira, wrote about this for the BBC News in an article titled: Papua unrest: Social media bots ‘skewing the narrative’. They wrote:

“The Twitter accounts were all using fake or stolen profile photos, including images of K-pop stars or random people, and were clearly not functioning as ‘real’ people do on social media.

“This led to the discovery of a network of automated fake accounts spread across at least four social media platforms and numerous websites.”

Fake Facebook accounts removed

Reuters reported that more than 100 fake Indonesian Facebook and Instagram social media accounts were removed for “coordinated inauthentic behaviour”. Five months later, in March this year, Facebook and Twitter pulled about 80 websites publishing pro-military propaganda about Papua.

In February 2019, Reuters had earlier reported Facebook removing “hundreds of Indonesian accounts, pages and groups from its social network” after discovering they were linked to an online group called Saracen.

This syndicate had been identified in 2016 and police had arrested three of its members on suspicion of being being paid to “spread incendiary material online” through social media.

For the moment, we would be delighted if Facebook would remove the block on our shared items and not censor future dispatches or genuine human rights news items about West Papua.

The truth deserves to be told.

POSTSCRIPT: Since this article was published, I have been contacted by Miranda Sissons, Facebook’s director of human rights product policy, apologising for the “frustrations” and lack of a response.

“Covid has had a huge impact on our content moderation capacity (see for example here). We are prioritising appeals capacity according to severity of harm (eg suicide and self injury or child endangerment),” she wrote.

“We’re also using guidance from the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights to prioritise according to scale, severity, and remediability of human rights violations.”

She has put me in touch with people who I understand will sort out the problem.