On 10 July 2023 — marking the 1985 bombing of the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior — Television New Zealand began broadcasting a BBC/Oxford Scientific documentary miniseries, Rainbow Warrior: Murder in the Pacific, about the Rongelap humanitarian voyage and the subsequent state terrorism by French secret agents. Republished here is David Robie’s cover story in the US Greenpeace magazine in 1989.

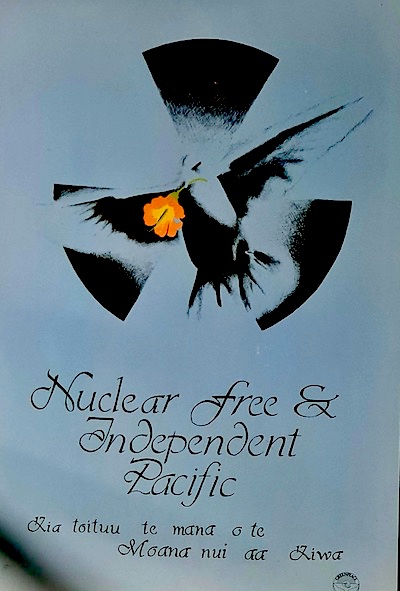

“We, the people of the Pacific, have been victimised too long by foreign powers . . . Alien colonial, political and military domination persists as an evil cancer in some of our native territories, such as Tahiti-Polynesia, Kanaky, Australia and Aotearoa [New Zealand]. Our environment continues to be despoiled by foreign powers developing nuclear weapons for a strategy of warfare that has no winners, no liberators and imperils the survival of all mankind . . . “

— From the preamble to the People’s Charter for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific.

By David Robie

December 1984: Ten militant activists are massacred by mixed-race French settlers near the Kanaky New Caledonia township of Hienghene. March 1985: New Zealand prohibits the entry of US warship. June 1985: President Haruo Remeliik of the nuclear-free state of Belau/Palau is assassinated. July 1985: French secret agents blow up the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior in Aotearoa New Zealand, killing one crew member. May 1987: A rightwing military coup topples the elected nuclear-free government of Fiji. May 1988: Kanak militants in New Caledonia take French gendarmes hostage on the island of Ouvéa, declare an insurrection and are killed by French government troops. August 1988: Remeliik’s successor, Lazarus Salii, commits suicide.

Although separated in some cases by thousands of kilometres of open ocean, these incidents in the now not-so-peaceful South Pacific are linked in essence; they represent a loss of geopolitical innocence, a sign that nationalist aspirations in Oceania are rekindling in new forms, with troubling and sometimes violent implications.

- READ MORE: Rainbow Warrior redux: French terrorism in the Pacific

- Independence for Kanaky: A media and political stalemate or a ‘three strikes’ Frexit challenge?

- The insecurity legacy of the Rainbow Warrior affair: A human rights transition from nuclear to climate-change refugees

Western observers who speak of the “Pacific Century” restrict their analysis to economics — specifically to the “successes” of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. For most of the Pacific’s island nations, however, there is little that is miraculous. On the contrary, three decades of the pervasive and overpowering influence of France and the United States has skewed Pacific politics, spawning local anomalies that pit nation against nation and people against people.

The consequences of this foreign presence are clear — the stereotyped image of the Pacific as a region of untroubled idyllic island paradises has been irreparably shattered.

Promise of riches

The Pacific Ocean covers nearly a third of the world’s surface and is home to more than 5 million indigenous islanders. And for 400 years, these people have lived under the flag, nominally and otherwise, of various Western nations. At first, Western interests in the scattered islands were largely economic. At the time of of Captain James Cook’s “discovery” of New Caledonia in 1774, noted one historian, voyages of exploration in the region were “motivated as much by scientific curiosity as the lure of gain”.

But the promise of riches in the scattered islands proved illusory. As a result, colonialism tended to be superficial; the French and the British, who superseded Spain as the dominant power in the region in the 19th and early 20th centuries, ruled in an offhand way, in one case through a bizarre French-British condominium, with minimal administration. The economic rewards were not great enough to warrant the expense of direct rule over the sparsely populated islands.

Thus, while Africa, Asia and the Caribbean were embroiled in intense and often violent liberation struggles after World War II, the Pacific enjoyed tranquil or even stagnant relations with its metropolitan overlords. In fact, by the mid-1960s, when the decolonisation process had been virtually completed in most parts of the world, it had barely begun in the South Pacific.

It was not until the late 1960s that a fresh political geography began to emerge in the South Pacific. in a decolonisation process that was remarkably peaceful, name changes and new nations altered maps, as the last outposts of the European empires were cast adrift. Britain in particular had no qualms about letting its unprofitable wards loose, such a Fiji in 1970. A the same time, Tonga shed its protectorate status.

New Zealand had already accepted the early independence of Western Samoa in 1962, later granting self-government to the Cook Islands and Niue. Australia shed iys trusteeship of Nauru and eventually bowed to Papua New Guinea’s desire for independence. This was followed by Tuvalu (formerly the Ellice Islands) and the Solomon islands in 1978, Kiribati (Gilbert islands) in 1979 and Vanuatu (New Hebrides) in 1980.

The 1980 independence of Vanuatu became the turning point in the politics of the region. That year, French-speaking Melanesians, partly financed by American business interests and supported by the French colonial administration, staged the Santo rebellion. Although French commercial interests in the plantation economy had waned several years before, France belatedly decided to sabotage independence in Vanuatu because it feared the impact of decolonisation on New Caledonia (also known by its indigenous name, Kanaky) and Tahiti Nui (“French” Polynesia).

Eventually, overcome by Vanuatu’s fledgling government with the help of troops from Papua New Guinea, the Santo rebellion ended the first phase of decolonisation in the region and heralded a new era of growing conflict and uncertainty.

The rebellion also brought about the development France feared most: since independence, Vanuatu, under the leadership of Prime Minister Father Walter Lini, has championed the cause of the Kanak and other independence movements in the region. And Father Lini is leading the campaign against the increased nuclearisation of the region and for a “niuklia fri Pasifik”, as it is called in Vanuatu’s national pidgin language, Bislama.

Less well known, and considerably more bloody, are the guerrilla wars that continue to be waged by Melanesian liberation groups in southwestern Pacific territories of East Timor and West Papua (Irian Jaya, which borders Papua New Guinea). Afrer Indonesian troops invaded both territories (West Papua in 1962 and East Timor in 1975), the United Nations recognised the annexation of West Papua but not East Timor. More than 200,000 Timorese, a third of the country’s population, have died in battle or have been executed by Indonesian troops, or have starved to death — a level of atrocity comparable to the carnage that gripped Cambodia at the hands of the Khmer Rouge.

Today, France and the United States are the only other Western countries retaining clear and complete control over regions of the South Pacific. The concrete manifestations of this presence is nuclear; both nations have built extensive nuclear-related facilities in the region, and France maintains a nuclear testing programme that has exploded nearly 150 bombs in the fragile basalt beneath Polynesia’s Moruroa atoll.

As a result, the aspirations for independence of the people of the Pacific have become paired with their desire to be free of nuclear weapons, giving rise to the catch-all name the loose Pacific colaition has taken on: the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) movement.

Tightened grip on Kanaky

Since the aborted attempt to scuttle Vanuatu’s bid for independence, France has tightened its grip on “French” Polynesia and Kanaky New Caledonia. France justifies its presence here in part by raising the spectre of Soviet interference and in part by simple declaration, supporte by vocal and strident French immigrants, that Polynesia and New Caledonia are part of France.

The first argument, although widely accepted, is hardly supportable. The Soviet strategic position in the North Pacific is bleak, as even senior American commanders admit, and it is negligible in the South Pacific. A major part of the Soviet military presence in the hemisphere is directed toward China. Unlike the United States, the Soviet Union has few forward bases and a limited military capability beyond its territory. Moreover, according to one political analyst, the region is “almost extraordinarily devoid of communist parties or Marxist political groups”. However, like the United States, the Soviet Union has deployed an inordinately powerful nuclear arsenal.

The real reasons for France’s unwelcome range from the economic t the purely psychological. Economically, the region is a drain on France; maintaining the military presence alone costs nearly 2 billion French francs a year. But the possession holds the promise of future riches; the islands include the world’s second largest 200-mile offshore economic zone.

As to the psychological, France’s foreign policy can be interpreted, in the words of one domestic critic, as an “attempt to resurrect past grandeur in the absence of the means that had once made it possible”. This past grandeur is dependent, from the perspective of France’s military, on France’s nuclear capacity, its “Force de Frappe”.

Moruroa is the linchpin of France’s nuclear weapons programme. Thus Kanaky, in France’s eyes has become a domino; any threat to French control over New Caledonia/Kanaky is a threat to Moruroa and consequently to France’s position as a global power. France has the second largest global distribution of military bases after the United States, stretching like stepping stones from France to Djbouti to Mayotte to Reunion to New Caledonia to Tahiti to Martinique to Senegal and back to France.

“Geography,” remarked the Noumea newspaper Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, “has turned New Caledonia into a [French] aircraft carrier.” As Paul Dijoud, France’s former State Secretary for Overseas Territories, put it, “Battle must be done to keep New Caledonia French.”

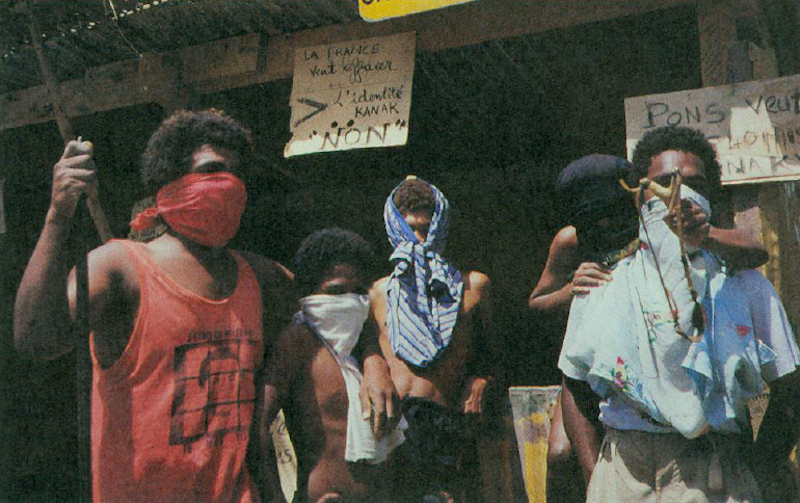

Dijoud can be taken literally. The “battle” in the case of New Caledonia, has cost dozens of lives — 32 as a result of the 1984-85 Kanak insurrection, including 10 in the Hienghène massacre, and another 25 during the two week revolt by Kanak militants at the time of the French presidential elections in May 1988.

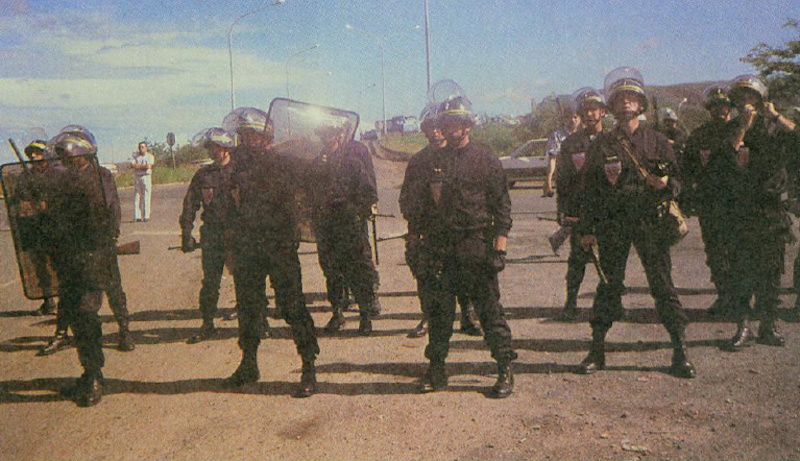

France’s reaction to the unrest has been decidedly obstinate. It has increased the militarisation of the islands; a referendum on independence for Kanaky in 1987 was held in the presence of 8400 soldiers and paramilitary gendarmes — one for every six Kanak people. The Australian ambassador to the UN, Richard Woolcott, subsequently called the vote “fundamentally flawed”. And a French court acquitted the seven self-confessed killers in the Hienghéne massacre, a ruling that provoked the bloody Ouvéa uprising. As for the criticism of its nuclear presence, French Defence Minister Andrew Giraud told an Australian television audience, “It’s not your country. Mind your own business.”

However, the new Socialist government, led by Prime Minister Michel Rocard, has offered a glimmer of hope with the so-called Matignon peace accord. Endorsed by an historic national referendum last November, the 10-year plan calls for dividing New Caledonia into three self-governing provinces, followd by a vote on self-determination in 1998. Although still cautious, the Kanak independence movement hopes this process will lead to decolonisation.

Fiji coup ‘sits uncomfortably’

In this context, one of the region’s most publicised political developments, the Fiji coup of May 1987, sits uncomfortably alongside the independence struggles of its neighbouring islands. In April 1987, Dr Timoci Bavadra’s Labour Party-led multiracial coalition was elected. Dr Bavadra, himself an indigenous Fijian and a former trade unionist, pledged far-reaching reforms. The coalition government also declared it would become non-aligned, ban nuclear warships and support other Pacific nationalist struggles — foreign policies in common with Vanuatu and other Melanesian states.

In retaliation, the extreme rightwing Taukei movement exploited rivalries between indigenous Fijians, who are Melanesians, and the Indo-Fijians who slightly outnumber them, embarking on a campaign of subversion and violence. In the West, the conflict was portrayed as purely racial, a simplification that belies the class conflict that played a larger role in the crisis.

When the coalition was deposed by Major-General Sitiveni Rabuka (at the time of the coup he was a lieutenant-colonel and the third-ranked officer in the Fiji military) a month later, many of the key people in the defeated oligarchy of Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, which had been accused of growing corruption, regained power. Rabuka, declaring his narrow sectional an indigenous rights movement, has maintained control through measures such as the Internal Security Decree in June 1988, which gave the military and police virtually unlimited powers. Fiji is now the first totalitarian country in the South Pacific.

Although the coup provoked cries of outrage in neighbouring countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, and in the Commonwealth, several Pacific nations were reluctant to criticise this Pacific rarity, a violent change of government, because they saw it as a victory for indigenous sovereignty and traditional land rights.

Not surprisingly, the reversal of Fiji’s antinuclear policy met with tacit approval of French and US military strategists. France, which has an overt political agenda to its Pacific aid programme, has since packaged an $18 million aid programme for Fiji and supplied it with military helicopters and other hardware, effectively endorsing the coup.

Nuclear free and independent Pacific ‘a threat’

American and French strategists regard the campaign to make the Pacific “nuclear free and independent” as a major threat to their interests. As a former US Ambassador to Fiji, William Bodde Jr, warned in 1982, “The most potentially disruptive development for US relations with the South Pacific is the growing anti-nuclear movement in the region. The US government must do everything possible to counter this movement.”

It seems clear from recent history that this policy actually may prove more inimical to the interests of both the Western countries and the Pacific nations han one that acknowledges and adjusts to the region’s desires for independence. Moreover, time will work against France and the United States. As old guard leaders in the Pacific Islands either die or lose authority at the ballot box, younger more radical leaders are emerging to take their place.

Among national leaders with a more progressive outlook are Vanuatu’s Father Walter Lini, President Ieremia Tabai of Kiribati and Fiji’s Dr Bavadra. Others in nationalist movements include Jean-Marie Tjibaou, a poetic visionary of Kanaky New Caledonia, and Tahiti’s Oscar Temaru and Jacqui Drollet.

The newcomers have given a dynamic and crusading voice to the region’s unspoken wishes. “The great ocean surrounding us carries the seeds of life. We must ensure they they don’t become the seeds of death,” said Tjibaou in a moving speech before the 1985 signing of the Rarotonga Treaty (see sidebar in US Greenpeace magazine, p. 10). “A nuclear-free Pacific is our responsibility, and we must face the issues to live and protect our lives.”

This article was originally published in the US Greenpeace magazine, January/February 1989 (pp. 6-10). Barely three months later, Jean-Marie Tjibaou and his deputy, Yeiwene Yeiwene, were assassinated on 4 May 1989. At the time of writing, David Robie was a New Zealand-based journalist specialising in Pacific affairs. He sailed on the Rainbow Warrior in 1985 and is author of Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior (New Society Publishers, available through Greenpeace) about the 1985 bombing by French secret agents. His 1989 book, Blood on their Banner: Nationalist Struggles of the South Pacific (Zed Books, London), was about to be published.