REVIEW: By Ken Mansell

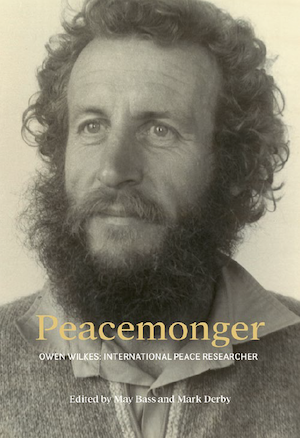

The recent publication of a book of essays honouring the life of legendary New Zealand peace researcher and activist Owen Wilkes is a must read for historians of social movements, those who were active in the anti-nuclear and peace movements of the seventies and eighties, as well as those growing numbers who today carry on the resistance to escalating militarism.

Wilkes, an iconic figure revered in the Peace Movement, exposed covert military activity worldwide and inspired many in the fight for New Zealand’s nuclear-free status.

Thirteen of Owen’s contemporaries, all of whom were associated with him in his peace movement activities, have contributed essays. They are New Zealanders Mark Derby, May Bass, Robert Mann, Ken Ross, Murray Horton, Maire Leadbeater, Diane Hooper, David Robie, Peter Wills, Nicky Hager, and Neville Ritchie; and the Norwegians Ingvar Botnen and Nils Petter Gleditsch.

- READ MORE: Owen Wilkes: Exposing foreign militarism on the ‘backside of the earth’ – David Robie

- Lots of information isn’t secret, it’s just hard to find’ – Nicky Hager on one of NZ’s most famous whistleblowers

- Other Owen Wilkes articles

Their individual memories combine and overlap to provide a detailed biographical sketch. It has not been possible to write a conventional review because this would have required a review of each of the various essays.

I have, however, drawn on the contents of each essay to pen, in summary form, the story of Owen’s extraordinary life. Here I mainly have an Australian reading audience in mind.

Owen Wilkes was a household name in New Zealand but was comparatively unknown in Australia beyond those, like myself, who knew him in the Australian peace movement of the eighties. Hopefully, however, my article, because it includes Owen’s exploits on this side of the ditch, will also arouse some interest in Aotearoa.

Who then was Owen Wilkes?

Owen Wilkes – peace researcher

Owen, born in 1940 and raised in Christchurch, dropped out of university in 1960 but soon displayed a remarkable proclivity for exposing the hidden and obscure, initially on Māori rock art digs for the Canterbury Museum (1963-64) and then in jobs that awakened him to hidden militarism.

As a field entomologist in Papua New Guinea, Owen exposed a secret US Army germ warfare research programme; at the US McMurdo Sound Antarctic base, he found evidence that Christchurch Airport’s “Operation Deep Freeze” was a cover for US military activity (and later exposed the installation of a small nuclear reactor at the base); at the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, he responded to the horror of the Vietnam War by researching US military activities in New Zealand and the Pacific.

In June 1968, the New Zealand government proposed to establish an Omega transmitter in the South Island high country, ostensibly only for civilian navigation purposes. Owen acquired a 364-page report from the US Navy Omega Implementation Committee that described Omega’s role in sending VLF signals to submerged ballistic missile submarines, enabling them to locate their position and calculate trajectories to their targets.

Canta, the University of Christchurch student newspaper, published 72,000 copies of a special Omega edition featuring an article by Owen. Three days later, 4000 marched in protest through the streets of Christchurch. Owen Wilkes, a pioneer peace researcher, was now a household name.

A militant anti-bases movement was built in New Zealand, inspired by Owen’s knowledge and leadership. In the early 1970s, he exposed two US Air Force operations, “Project Longbank” (monitoring nuclear tests by France and China) and the Mt John Observatory (providing targeting data for a US anti-satellite weapons system), and found that Christchurch Airport (Harewood) was being used to service American spy bases in Australia under cover of the Antarctic “Operation Deep Freeze”.

In the 1980S, Owen uncovered the role of the Black Birch US Naval Observatory in improving the stellar guidance system of long-range missiles (Trident, MX) and the role of two electronic spy bases linked to the US National Security Agency — at Tangimoana in the North Island (contributing to the targeting of US naval weapons) and at Waihopai in the South Island (targeting the international Intelsat system).

From 1976-1982 Owen lived in Scandinavia and worked for peace research institutes in Oslo and Stockholm. At the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), he researched technical intelligence systems (sonars, seismometers detecting nuclear explosions) and foreign military installations linked to nuclear weapons command and control systems (including navigation aids for nuclear missile submarines). For the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), he compiled a database of 1500 US bases and 300 Soviet bases, and contributed articles to three SIPRI Yearbooks.

The security services in both countries cracked down hard on him. Owen had been subjected to surveillance and harassment (opening of mail) in New Zealand, but his treatment at the hands of the security state in the Nordic countries went beyond this level.

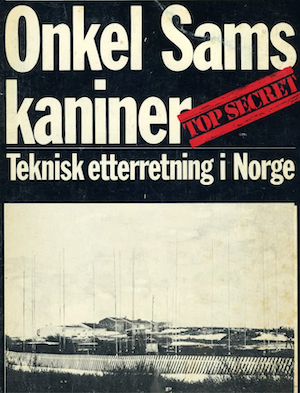

Owen and PRIO colleague Nils Petter Gleditsch discovered that Norway was secretly hosting NATO/U.S electronic direction-finding bases (“Uncle Sam’s Rabbits”). This brought charges under the Official Secrets Act and a June 1981 trial in the City Court of Oslo, where they were fined and given suspended prison sentences (confirmed by the Norwegian Supreme Court in February 1982).

Owen’s arraignment in Sweden was even more dramatic. After an innocent bicycle tour of the Swedish island of Götland, where he stopped occasionally to photograph or jot down notes about glaringly public antennae, Owen was grabbed by secret police on a charge of “espionage”, later revised to the spurious “piecing together data from open sources and field observations”.

His suspended sentence and deportation for 10 years meant that Owen left Sweden in a blaze of publicity and with an international reputation as a “spy”. One interesting suggestion in an endnote is that SIPRI disapproved of Owen’s adventurous fieldwork and failed to defend him (and its own independence).

‘Jigsaw puzzle principle’

In their detailed treatment of Owen’s research methods, the investigative journalists David Robie and Nicky Hager are both at pains to refute the charge of “espionage”. What really offended the Defence authorities was the “jigsaw puzzle principle” — Owen’s ability to piece together information from multiple publicly available (albeit obscure) open sources (such as what could be gleaned from US Congressional hearings, Defence Department reports to Congress, and aerospace trade journals) to create new information that governments wanted to keep secret.

Many of Owen’s insights and discoveries were the result of “fieldwork”, where the self-taught researcher used his expertise to deduce the functions of military installations (antennae and radar systems) simply from observing them. His efforts resulted in a vast store of accumulated knowledge about electronic signals intelligence systems, and communication systems for land/sea-based nuclear forces.

Hager describes Owen’s meticulous filing system, every page having a file code, allowing him to write about a wide variety of subjects, such as, for example, his history of New Zealand’s involvement with chemical warfare.

Based in Wellington from 1984-1994, where he worked for Peace Movement Aotearoa (PMA), much of the time in libraries (Alexander Turnbull; US Embassy), Owen increasingly widened his investigative scope to include foreign military activities across the whole of the Pacific, including the intelligence (spying) activity associated with it.

He conducted speaking tours of “intelligence sites” in Wellington and exposed the destabilising activity of the CIA in New Zealand (Māori Loans Affair) and the Pacific (Fiji) with his articles in PMA’s Peacelink and in the newsletters Wellington Confidential and Wellington Pacific Report. Owen was dedicated to sharing his documents with peace researchers and with activists. Likewise, his discoveries, such as when Owen informed the anti-nuclear movement in the Philippines of the existence of a secret US nuclear test detection facility in Bukidnon, Mindanao.

Owen Wilkes in Australia

Owen Wilkes made an enormous contribution to the anti-nuclear and peace movements in Australia from the early 1970s to the early 1990s. Very little of this aspect of Owen’s career is covered in Peacemonger, so here I’ll fill in some of the gaps. Owen’s association with the peace movement in Australia started soon after the announcement in March 1971 that an Omega transmitter, having been rejected by New Zealand in May 1969, would be sited in Australia.

Owen was hosted by the Melbourne Stop Omega Committee and produced (with Albert Langer) a detailed submission on Omega’s military role as a navigation aid for Polaris ballistic missile submarines to the (August-November 1973) hearings of the Australian Parliamentary Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defence.

Owen was one of 11 New Zealanders who participated in the 1974 “Long March” to North West Cape, a three-week-long bus trip to Exmouth in Western Australia, the site of the sprawling US Navy nuclear submarines communications base. The North West Cape demonstrators benefited from Owen’s knowledge and leadership and inspired the 1975 South Island “Resistance Ride” in New Zealand.

Originally earmarked for Tasmania (and then Boort in north-west Victoria), Omega was eventually constructed near Sale in Gippsland but only after a vigorous anti-base campaign had delayed its opening until 1982.

On 28 August 1982, in Melbourne, the fledgling People for Nuclear Disarmament (PND) movement held a seminar on Omega as part of the preparation for a protest rally at the site later in the year. Owen, one of three listed speakers, arrived late after having passed through Sydney on his return from Stockholm. His deflating message was that he had changed his mind about Omega.

The system had originally been intended to play a role as a navigation aid for ballistic missile submarines but was now unlikely to be used by them because it had been sidelined by the more advanced VLF radio navigation system of Loran-C. Omega was more useful to “hunter-killer” (attack) submarines and to other anti-submarine warfare systems, and as such, was still involved in counterforce nuclear strategies against Soviet military forces.

On September 2, Owen called a press conference in Wellington to convey the same message, admitting publicly he had been partially wrong in his original criticism of Omega.

In the years that followed, Owen maintained contact with the growing Australian nuclear disarmament movement. He regularly posted copies of documents across the Tasman to Australian researchers and was welcomed here as an expert guest speaker at public meetings and on the radio.

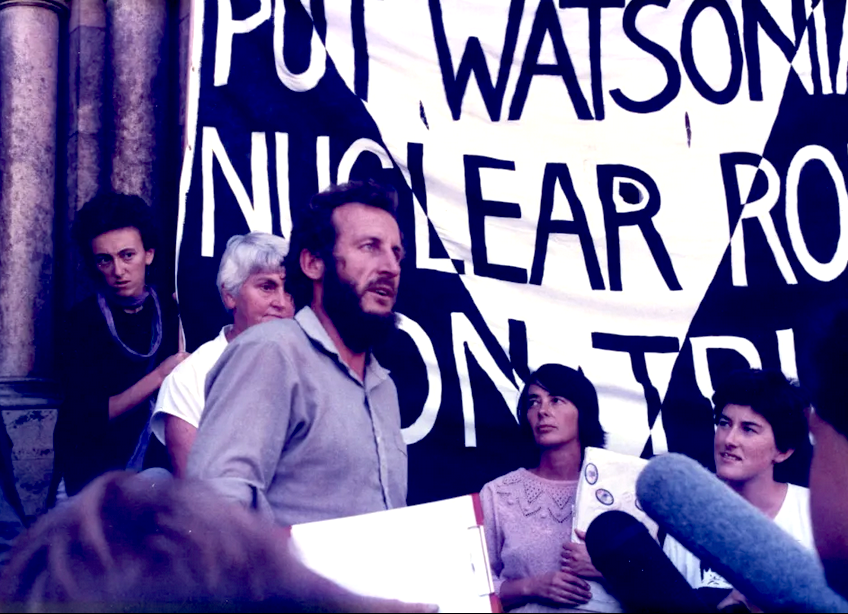

Owen visited Melbourne in July 1984 and completed four separate speaking engagements in the space of a week, including a meeting of the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) movement and a meeting of the group organising a peace camp at the satellite terminal in suburban Watsonia (confirmed by Owen as involved in the US Naval Ocean Surveillance Information System).

In March 1986, Owen appeared as an expert witness for the Christian activists on trial in the Melbourne Magistrates Court for splashing blood on the Watsonia dish at Easter 1985 and was eagerly sought for interviews by the Watching Brief public broadcast team.

In June 1988, Owen (accompanied by CAFCA organiser Murray Horton) again made the trip to North West Cape for the demonstration organised by the Australian Anti Bases Campaign Coalition and then followed up with a month-long speaking tour focusing on the destabilisation of the Pacific.

In early 1990, Owen lived in Melbourne for several weeks, taking the time for a spot of “fieldwork” while researching (with Peter Hayes) the history of US ballistic missile testing in the Pacific for the 1991 Nautilus Pacific Research publication Chasing Gravity’s Rainbow. No wonder that Owen filled multiple file boxes about Australia.

Owen Wilkes – the man (1940-2005)

Owen Wilkes was always much more than simply a busy and committed peace researcher. Most of the chapters in the book are also mini-biographical sketches that variously describe aspects of Owen’s personal life and his many interests and preoccupations outside of the peace movement.

In his earlier years, Owen supported his activism with a succession of part-time jobs as dustman, tomato grower, baker, ski field attendant and beekeeper. A lover of the outdoors and proudly Spartan in lifestyle, he lived at one time in a railway carriage as a member of a remote West Coast hippy commune, at another time in his own self-built energy-efficient house.

In 1995, Owen took permanent leave from the peace movement and worked for the Department of Conservation on an inventory of archaeological sites, a life-long passion. He spent his final years living in remote Kawhia, yachting, sailing, tramping, and tending to his vegetable garden.

The contributors to Peacemonger have explained why Owen Wilkes was such a revered activist. Explaining his personal characteristics would have been more difficult, but they have not shied away from it, describing him as a complex, eccentric personality with many admirable qualities (“stubborn, but generous and honest”, according to his partner May Bass).

Several of the essays, however, contrast Owen’s physical sturdiness — in Sweden he was known to ski in shorts with the temperature as low as minus 25 centigrade — with his apparent psychological fragility. As a researcher and campaigner, Owen displayed an iron will, but he was also prone to occasional debilitating depression and negativity.

In the 1990s, Owen took issue with the New Zealand peace movement, his somewhat hostile and cranky views including the outlandish notion that visiting nuclear-powered ships were perfectly safe. However, none of this could have prepared all who knew and revered him for the shock and devastation they would feel upon learning that Owen had taken his own life.

RIP Owen Wilkes.

Ken Mansell contributed this review to Labour History, the website of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, and it is republished by Café Pacific with the permission of both the author and society.

- Peacemonger, Owen Wilkes: International Peace Researcher, edited by May Bass and Mark Derby. Wellington: Raekaihau Press, 2022. 196 pages. Published in association with Steele Roberts Aotearoa.