Reviewed by Dr David Robie

As the editor, American-Kiwi anarchist, dissident and activist Valerie Morse notes in the preface to Peace Action, this practical treatise on the struggle for Moana liberation, justice and peace has a clear target. It is aimed at “deepening connections and amplifying impact for the urgent work of building a radically different ‘new world in the shell of the old’ (p. 11).”

However, it is the opening chapter, “Setting the Scene”, by researcher and environmental advocate Tina Ngata (Ngāti Porou), which sets the tone for this indictment of settler colonialism with an introduction to the 11th-12th century Crusades and the following notorious Doctrine of “Discovery”. She lays the blame on Pope Urban II for unleashing the seizure of lands for Christendom and converting people living there “by force if necessary (p. 13).”

In the name of the Roman Catholic Church, the Pope “excused” people from the punishments of mortal sins carried out as “acts of war” on behalf of God and the Bible. He issued Papal Bulls — church laws — that gave divine authority for “not just murder, not just theft, not just dispossession, not just rape” in church-ordained crusades in the Holy Lands against the Muslim Saracens (p. 13).

Following in the 15th century, Pope Nicholas granted three Papal Bulls giving permission to “invade, to subdue, to dispossess and to commit to perpetual slavery any people that the crusaders encountered” for profit. These Papal Bulls became known as the Doctrine of Christian “Discovery” and led to the transatlantic slave trade that claimed the lives of 30 million Africans (p. 14).

It was the application of these three Papal Bulls — Dum Diversas, Romanus Pontifex and then Inter Caetera — beyond West Africa to the New World and so-called Age of Discovery that eventually reached the Pacific. Not only did these laws “give permission”, but they imposed a Christian duty on European royalty to “acquire land and souls”.

When Ferdinand Magellan “discovered” Te Moana-Nui-A-Kiwa in 1519 and rebranded it the “Pacific”, the Doctrine of Discovery had arrived in this part of the world and explains the context of James Cook’s first voyage in 1768 and the two others that followed. Ngata writes:

“Cook’s modus operandi was to abduct the leaders of communities to force the local people into doing something for him as a means of collective punishment. In Tahiti, he abducted Poetua, the young pregnant daughter of the local ariki [chief], Oreo, in order to force the local people into bringing back two of his men who ad absconded of their own free will to evade Cook’s increasingly irrational behaviour. (p. 17)

Ngata stresses that Cook carried out these kidnappings numerous times across the three voyages until he was “murdered while trying to abduct Kalani’ōpu’u, the high chief of the island of Hawai’i” (p. 17).

This introductory chapter about the “toxic, imperial masculinity and infection” (p. 18) of the Palagi and resistance by Moana people leads seamlessly into the third chapter, “Protecting Ihumātao”, by Qiane Matata-Sipu, Pania Newton and Frances Hancock, an inspirational account of how a 1100 acre “food bowl for the developing city of Tāmaki Makaurau [Auckland]” was unjustly seized in 1863 by the colonial government under the New Zealand Settlement Act (p. 37).

“Our tūpuna [ancestors] were exiled to the Waikato, their homes destroyed and their whenua [traditional lands] granted to settlers. Upon their return to Ihumātao, effectively landless and reduced to subsistence living, our tūpuna took up the struggle to reclaim their whenua.” (p. 38)

Subsequent injustices followed with the ancestral lands being subjected to quarrying for roads, pollution of moana for Auckland’s wastewater treatment plant, and industrial encroachments, including a chemical dye spill. “We were told these were our sacrifices for the greater good of Auckland,” lament the co-authors (p. 37).

In 2015, the Indigenous and youth-led, community supported campaign with peaceful, passive and positive resistance “touched hearts and called tens of thousands of New Zealanders to action” (p. 49).

Seven years on, the #ProtectIhumātao campaign has thwarted the property development scheme of a multinational, and achieved the highest heritage listing status for the contested lands and Ōtuataua Stonefields Historic Reserve. A feature of this chapter is the articulated campaign strategy plan — a recipe for activist success.

However, these are just two of the 13 chapters by 23 contributors and a photoessay, “Reclaiming the whenua at Ihumātao”, by social justice photographer Jos Wheeler in this wide-ranging Pacific peace activism manifesto. In addition, there are two superb colour plates, Arama Rata’s “Watery Grave” and Marylou Mahe’s “Te Temps Kanak/Kanak Time”. Topics range from French, Indonesian and US colonialism and militarism, feminist resistance, peace gardening at Parihaka, and climate crisis action.

Some of the chapters feature anti-militarism in South Korea (Jungmin Choi); stories of “heartbreak and hope” in Hawai’i (Emalani Case); weaving an ‘upena [fishing net] of Oceanic solidarity in response to the imperial militarisation of Hawai’i (Kyle Kajihiro); and Takae residents struggling against US militarisation of Yanbaru forest in Japan’s Okinawa by Mizuki Nakamura, who quotes a fellow activist saying, “when the pandemic is over, we must not go back to destroying the environment but try to build a different world” (p. 97).

For me, three of the highlights are the essays “Standing with Ma’ohi Nui: Practising Moana solidarity in Aotearoa” (Tony Fala, Tokelauan/Palagi); “Papuaphobia: Colonial mythology behind Papuan holocaust” (Yamin Kogoya, Yikwa/Lani); and “Forever fighting France: the coloniser par excellence” (Ena Manuireva, Mangarevian/Aotearoa). All three authors are regular contributors to the independent Asia Pacific Report.

Writing about how “Ma’ohi Lives Matter”, Manuireva outlines the strategies of Oscar Temaru’s Tavini Huira’atira — the only Tahitian political party “still standing against French colonial governance”, including an appeal to the International Court of Justice in The Hague. He concludes:

“Colonisation is a deadly virus that spreads through the social, cultural and economic and above all political arenas of Indigenous societies to gain control of our vital resources. France has been doing this to the Ma’ohi people since November 1843. Fighting against colonialism/neocolonialism is an extension of our ancestors’ battle: they wanted to be their own masters and to decide their own future for themselves. So do we.” (p. 104)

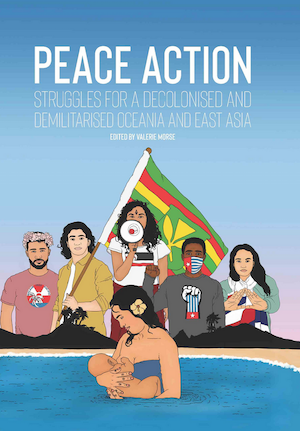

While this book’s target audience is primarily Aotearoa New Zealand, many of the essays have a wide Asia-Pacific relevance and there is an extensive glossary of Māori words and phrases. It is an invaluable and beautifully illustrated handbook of “peace action”, summing up the mahe (work) that needs doing for decolonisation and demilitarisation.

It is very well timed too having been published just weeks before a “reborn again” Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) conference at Otago University in November (Ōtepoti Declaration, 2022). The fight for Te Moana is in good guardianship hands with a new generation of activists and advocates.

- Peace Action: Struggles for a decolonised and demilitarised Oceania and East Asia, Edited by Valerie Morse. Wellington, NZ: Left of the Equator Press, 2022. 179 pages. ISBN: 978-0-47363445-2. This review was originally written for the Okinawan Journal of Pacific Studies.

Reference

Ōtepoti Declaration (2022). Indigenous Caucus of the Nuclear Connections Across Oceania Conference, Asia Pacific Report. https://asiapacificreport.nz/2022/12/01/oceania-indigenous-guardians-call-for-self-determination-on-west-papua-day/