ANALYSIS: By Shailendra Bahadur Singh and Amit Sarwal in Suva

Given the intensifying situation, journalists, academics and experts joined to state the need for the Pacific, including its media, to re-assert itself and chart its own path, rooted in its unique cultural, economic and environmental context.

The tone for the discussions was set by Papua New Guinea’s Minister for Information and Communications Technology Timothy Masiu, chief guest at the official dinner of the Suva conference.

The conference heard that the Pacific media sector is small and under-resourced, so its abilities to carry out its public interest role is limited, even in a free media environment.

Masiu asked how Pacific media was being developed and used as a tool to protect and preserve Pacific identities in the light of “outside influences on our media in the region”. He said the Pacific was “increasingly being used as the backyard” for geopolitics, with regional media “targeted by the more developed nations as a tool to drive their geopolitical agenda”.

Masiu is the latest to draw attention to the widespread impacts of the global contest on the Pacific, with his focus on the media sector, and potential implications for editorial independence.

In some ways, Pacific media have benefitted from the geopolitical contest with the increased injection of foreign funds into the sector, prompting some at the Suva conference to ponder whether “too much of a good thing could turn out to be bad”.

Experts echoed Masiu’s concerns about island nations’ increased wariness of being mere pawns in a larger game.

Fiji a compelling example

Fiji offers a compelling example of a nation navigating this complex landscape with a balanced approach. Fiji has sought to diversify its diplomatic relations, strengthening ties with China and India, without a wholesale pivot away from traditional partners Australia and New Zealand.

Some Pacific Island leaders espouse the “friends to all, enemies to none” doctrine in the face of concerns about getting caught in the crossfire of any military conflict.

This is manifest in Fiji Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka’s incessant calls for a “zone of peace” during both the Melanesian Spearhead Group Leaders’ meeting in Port Vila in August, and the United Nations General Assembly debate in New York in September.

Rabuka expressed fears about growing geopolitical rivalry contributing to escalating tensions, stating that “we must consider the Pacific a zone of peace”.

Papua New Guinea, rich in natural resources, has similarly navigated its relationships with major powers. While Chinese investments in infrastructure and mining have surged, PNG has also actively engaged with Australia, its closest neighbour and long-time partner.

“Don’t get me wrong – we welcome and appreciate the support of our development partners – but we must be free to navigate our own destiny,” Masiu told the Suva conference.

Masiu’s proposed media policy for PNG was also discussed at the Suva conference, with former PNG newspaper editor Alex Rheeney stating that the media fraternity saw it as a threat, although the minister spoke positively about it in his address.

Criticism and praise

In 2019, Solomon Islands shifted diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China, a move that was met with both criticism and praise. While this opened the door to increased Chinese investment in infrastructure, it also highlighted an effort to balance existing ties to Australia and other Western partners.

Samoa and Tonga too have taken significant strides in using environmental diplomacy as a cornerstone of their international engagement.

As small island nations, they are on the frontlines of climate change, a reality that shapes their global interactions. In the world’s least visited country, Tuvalu (population 12,000), “climate change is not some distant hypothetical but a reality of daily life”.

One of the outcomes of the debates at the Suva conference was that media freedom in the Pacific is a critical factor in shaping an independent and pragmatic global outlook.

Fiji has seen fluctuations in media freedom following political upheavals, with periods of restrictive press laws. However, with the repeal of the draconian media act last year, there is a growing recognition that a free and vibrant media landscape is essential for transparent governance and informed decision-making.

But the conference also heard that the Pacific media sector is small and under-resourced, so its ability to carry out its public interest role is limited, even in a free media environment.

Vulnerability worsened

The Pacific media sector’s vulnerability had worsened due to the financial damage from the digital disruption and the covid-19 pandemic. It underscored the need to address the financial side of the equation if media organisations are to remain viable.

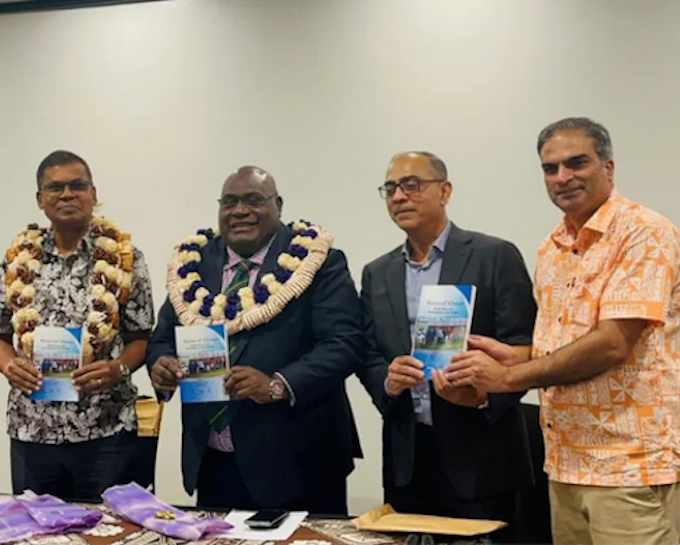

For the Pacific, the path forward lies in pragmatism and self-reliance, as argued in the book of collected essays Waves of Change: Media, Peace, and Development in the Pacific, edited by Shailendra Bahadur Singh, Fiji Deputy Prime Minister Professor Biman Prasad and Amit Sarwal, launched at the Suva conference by Masiu.

No doubt, as was commonly expressed at the Suva media conference, the world is watching as the Pacific charts its own course.

As the renowned Pacific writer Epeli Hau’ofa once envisioned, the Pacific Islands are not small and isolated, but a “sea of islands” with deep connections and vast potential to contribute in the global order.

As they continue to engage with the world, the Pacific nations will need to carve out a path that reflects their unique traditional wisdom, values and aspirations.

Dr Shailendra Bahadur Singh is head of journalism at The University of the South Pacific (USP) in Suva, Fiji, and chair of the recent Pacific International Media Conference. Dr Amit Sarwal is an Indian-origin academic, translator, and journalist based in Melbourne, Australia. He is formerly a senior lecturer and deputy head of school (research) at the USP. This article was first published by The Interpreter and is republished with permission.