In a keynote address at the 2015 University of the South Pacific (USP) journalism awards, Pacific Media Centre director Professor David Robie, formerly head of USP’s South Pacific regional journalism programme in its early stages, reflects on the progress and challenges facing media in the Pacific and worldwide. This is the first in a two-part report of his speech. Part two is here.

By David Robie

As I launched these awards here at the University of the South Pacific in 1999 during an incredibly interesting and challenging time, it is a great honour to return for this event in 2015 marking the 21st anniversary of the founding of the regional Pacific journalism programme.

Thus it is also an honour to be sharing the event with Monsieur Michel Djokovic, the Ambassador of France, given how important French aid has been for this programme.

France and the Ecole Supérieure de Journalisme de Lille (ESJ) played a critically important role in helping establish the journalism degree programme at USP in 1994, with the French government funding the inaugural senior lecturer, François Turmel, and providing a substantial media resources grant to lay the foundations.

I arrived in Fiji four years later in 1998 as head of journalism from the University of Papua New Guinea and what a pleasure it was working with the French Embassy on a number of journalism projects at that time, including an annual scholarship to France for journalism excellence.

These USP awards this year take place during challenging times for the media industry with fundamental questions confronting us as journalism educators about what careers we are actually educating journalists for.

When I embarked on a journalism career in the 1960s, the future was clear-cut and one tended to specialise in print, radio or television. I had a fairly heady early career being the editor at the age of 24 of an Australian national weekly newspaper, the Sunday Observer, owned by an idealistic billionaire, and we were campaigning against the Vietnam War.

Our chief foreign correspondent then was a famous journalist, Wilfred Burchett, who at the end of the Second World War 70 years ago reported on the Hiroshima nuclear bombing as a “warning to the world”.

Human rights, justice

By 1970, I was chief subeditor of the anti-apartheid Rand Daily Mail in South Africa, the best newspaper I ever worked on and where I learned much about human rights and social justice, which has shaped my journalism and education values ever since.

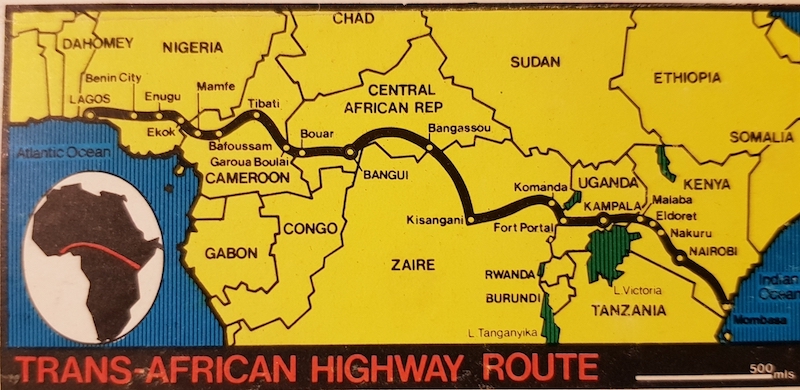

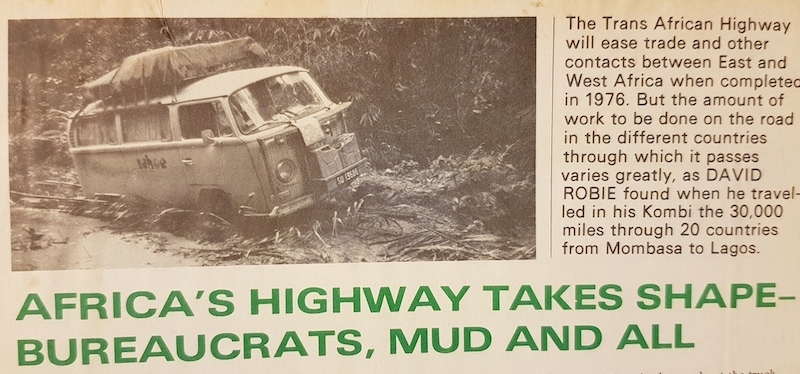

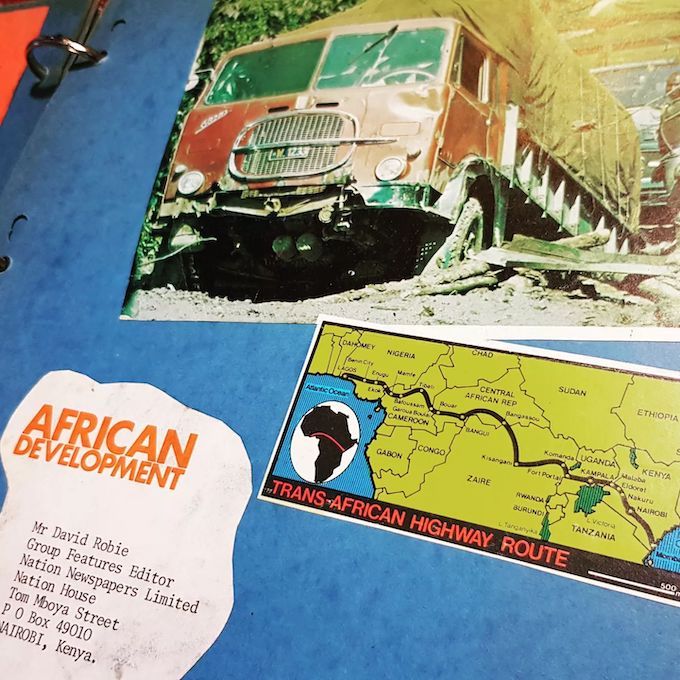

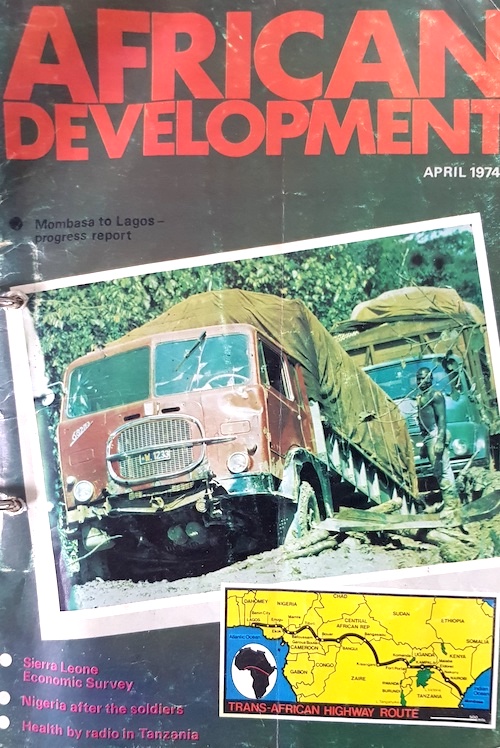

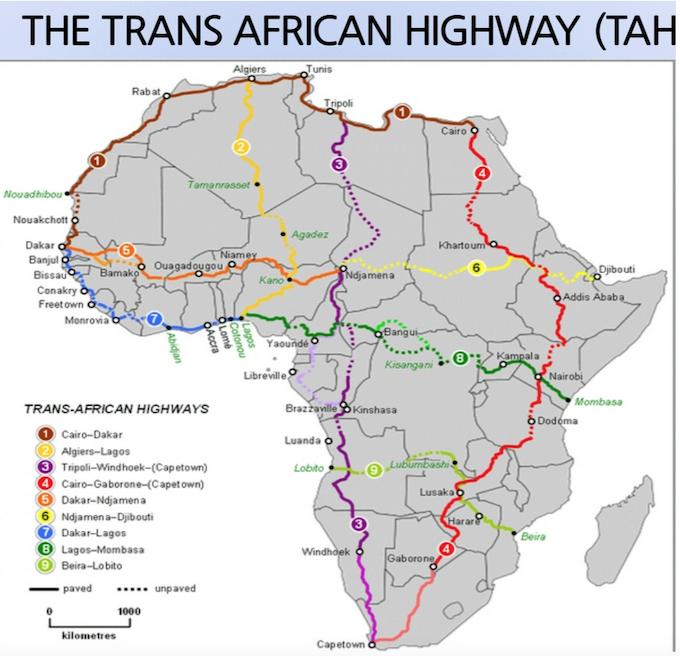

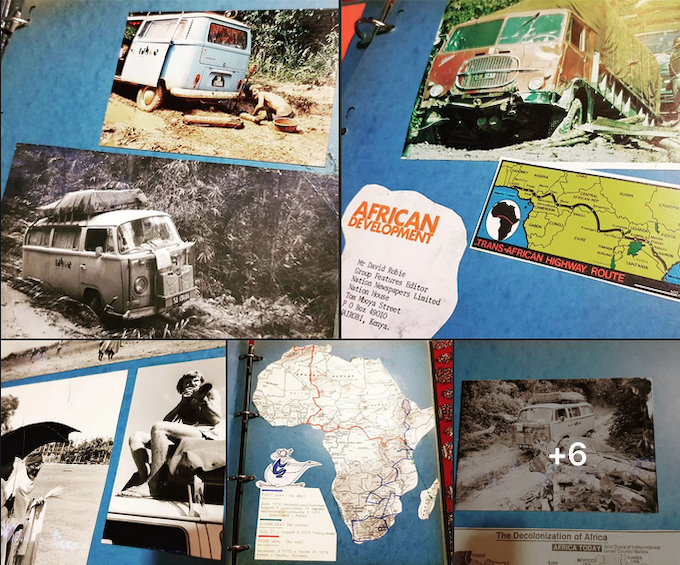

I travelled overland for a year across Africa as a freelance journalist, working for agencies such as Gemini, and crossed the Sahara Desert in a Kombi van. It was critically risky even then, but doubly dangerous today.

Eventually I ended up with Agence France-Presse as an editor in Paris and worked there for several years. In fact, it was while working with AFP in Europe that I took a “back door” interest in the Pacific and that’s where my career took another trajectory when I joined the Auckland Star and became foreign news editor.

The point of me giving you some brief moments of my career in a nutshell is to stress how portable journalism was as a career in my time. But now it is a huge challenge for you young graduates going out into the marketplace.

You don’t even know whether you’re going to be called a “journalist”, or a “content provider” or a “curator” of news — or something beyond being a “news aggregator”– such is the pace of change with the digital revolution. And the loss of jobs in the media industry continues at a relentless pace.

Fortunately, in Fiji, the global industry rationalisations and pressures haven’t quite hit home locally yet. However, on the other hand you have very real immediate concerns with the Media Industry Development Decree and the “chilling’ impact that it has on the media regardless of the glossy mirage the government spin doctors like to put on it.

We had a very talented young student journalist from the Pacific Media Centre here in Fiji a few weeks ago, Niklas Pedersen, from Denmark, on internship with local media, thanks to USP and Republika’s support. He remarked about his experience:

“I have previously tried to do stories in Denmark and New Zealand — two countries that are both in the top 10 on the RSF World Press Freedom Index, so I was a bit nervous before travelling to a country that is number 93 and doing stories there ….

“Fiji proved just as big a challenge as I had expected. The first day I reported for duty … I tried to pitch a lot of my story ideas, but almost all of them got shut down with the explanation that it was impossible to get a comment from the government on the issue.

“And therefore the story was never going to be able to get published.

“At first this stunned me, but I soon understood that it was just another challenge faced daily by Fiji journalists.”

Pacific leaders speak out with ‘one voice’ on climate change. Video: Niklas Pedersen/Pacific Media Centre

Climate storytelling

This was a nice piece of storytelling on climate change on an issue that barely got covered in New Zealand legacy media.

Australia and New Zealand shouldn’t get too smug about media freedom in relation to Fiji, especially with Australia sliding down the world rankings over asylum seekers for example.

New Zealand also shouldn’t get carried away over its own media freedom situation. Three court cases this year demonstrate the health of the media and freedom of information in this digital era is in a bad way.

• Investigative journalist Jon Stephenson this month finally won undisclosed damages from the NZ Defence Ministry for defamation after trying to gag him over an article he wrote for Metro magazine which implicated the SAS in the US torture rendition regime in Afghanistan.

• Law professor Jane Kelsey at the University of Auckland filed a lawsuit against Trade Minister Tim Groser over secrecy about the controversial Trans Pacific Partnership (the judgment ruled the minister had disregarded the law);

• Investigative journalist Nicky Hager and author of Dirty Politics sought a judicial review after police raided his home last October, seizing documents, computers and other materials. Hager is known in the Pacific for his revelations about NZ spying on its neighbours.

There is an illusion of growing freedom of expression and information in the world, when in fact the reverse is true

Legacy media failure

Also, the New Zealand legacy media has consistently failed to report well on two of the biggest issues of our times in the Pacific — climate change and the fate of West Papua.

One of the ironies of the digital revolution is that there is an illusion of growing freedom of expression and information in the world, when in fact the reverse is true.

These are bleak times with growing numbers of journalists being murdered with impunity, from the Philippines to Somalia and Syria.

The world’s worst mass killing of journalists was the so-called Maguindanao, or Ampatuan massacre (named after the town whose dynastic family ordered the killings), when 32 journalists were brutally murdered in the Philippines in November 2009.

Philippines : Testimonies of the Maguindanao massacre Video: Reporters Without Borders

But increasingly savage slayings of media workers in the name of terrorism are becoming the norm, such as the outrageous attack on Charlie Hebdo cartoonists in Paris in January. Two masked gunmen assassinated 12 media workers — including five of France’s most talented cartoonists — at the satirical magazine and a responding policeman.

In early August this year, five masked jihadists armed with machetes entered the Dhaka home of a secularist blogger in Bangladesh and hacked off his head and hands while his wife was forced into a nearby room.

According to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists in figures released this year, 506 journalists were killed in the decade between 2002 and 2012, almost double the 390 slain in the previous decade. (Both Reporters Sans Frontières and Freedom House have also reported escalating death tolls and declines in media freedom.)

This first part of Dr David Robie’s speech was first published by the Pacific Institute of Public Policy website. His history of Pacific journalism schools was published by USP as Mekim Nius: South Pacific Media, Politics and Education available on Tuwhera open access here.