COMMENTARY: By Yamin Kogoya

On 30 June 2022, the Indonesian Parliament in Jakarta passed legislation to split West Papua into three more pieces.

The Papuan people’s unifying name for their independence struggle — “West Papua” — is now being shattered by Jakarta’s draconian policies. Under this new legislation, the two existing provinces have been divided into five, which include South Papua, Central Papua, and Highland Papua.

Indonesia’s Vice-President, Ma’ruf Amin said while addressing an audience at the Special Autonomy Law Change in Jayapura, Papua’s capital, on Tuesday, 29 November 2022, “right now, we are building Papua better”, reported the Indonesian news agency Antara.

- READ MORE: Pacific marks 61st year flying of Papua’s banned Morning Star flag

- The Morning Star flag background

- Revelations on the murky fate of flag ‘treason’ prisoners in West Papua

- Oceania Indigenous ‘guardians’ call for self-determination on West Papua day

- Other West Papua reports

“Changes to special autonomy are a natural thing and are in the process of the national policy cycle to make things even better,” continued the Vice-President.

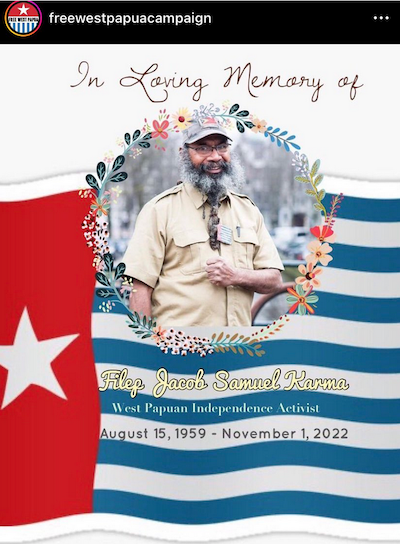

While Jakarta is busy tearing apart West Papua with these deceitful words, Papuans everywhere are called to raise the banned Morning Star flag today to commemorate West Papua’s 61st Independence Day on 1 December 1961, stolen by Jakarta in May 1963.

The day is significant and historic because it was on 19 October 1961 that the first New Guinea Council, known as Nieuw Guinea Raad, named West Papua as the name of a new modern nation-state — the Papuan Independent State was founded.

It was before Papua New Guinea (PNG) gained independence in 1975 from Australia.

Papuans were subjected to all kinds of abuse and violations due to how this island of New Guinea was named and described in colonial literature.

Foreign reinventions

Foreign powers continue to dissect West Papua, renaming it, creating new identities, and reinventing new definitions by making it merely an outpost of foreign imperialism in the periphery where abundant food and minerals are extracted and stolen, without penalty or consequence.

Papuans do not appear to give up their sacred ancestral land without a fight.

The name “West Papua”, however, remains a burning flame in the hearts of all living beings who yearn for freedom and justice. The name was chosen 61 years ago because of this reason. This is the name of a newborn nation-state.

After Indonesia invaded West Papua on May 1, 1963, the name West Papua was changed to Irian Jaya. West Papua had been called The Netherlands New Guinea up to the point of the first New Guinea Council in 1961.

The year 2000 marked another significant period in the history of West Papua. The former Indonesian president, Abdurrahman Wahid — famously known as Gusdur — renamed it from Irian Jaya to Papua, a move that etched a special place in the hearts of Papuans for Gusdur.

In 2003, not only did West Papua’s name change. But West Papua was split in half — Papua and West Papua. This fragmentation was achieved by Megawati Sukarnoputri, daughter of the first Indonesian president, Sukarno, the man responsible for 60 years of Papuan bloodshed.

She violated a provision of the Special Autonomy Law 2001, which was based on the idea that Papua remain a single territory. As prescribed by law, any division would need to be approved by the Papuan provincial legislature and local Papuan cultural assembly.

Tragic turning point

They were institutions set up by Jakarta itself to safeguard Papuan people, language, and culture.

One significant aspect of the first Special Autonomy Law was, any new policy introduced by the central government in relation to changing, adjusting, or creating a new identity of the region (West Papua) must be approved by the Papuan People’s Assembly (MRP). But this has never happened to date.

The year 2022 marks another tragic turning point in the fate of West Papua. West Papua is being divided again this year under President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, in the same manner that Jakarta did 20 years ago.

It is common for Jakarta elites to act inconsistently with their own laws when dealing with West Papua. Jakarta violated both the UN Charter and the New York Agreement, which they themselves agreed to and signed.

For example, chapters 11 (XI), 12 (XII), and 13 (XIII) of the UN Charter governing decolonisation and Papua’s right to self-determination, as specified in the New York Agreement’s Articles 18 (XVII), 19 (XIX), 20 (XX), 21 (XXI), and 22 (XXII) have not been followed. The words, texts and practices all contradict each other — demonstrating possible psychological disturbance — traumatising Papuans by being administered by such a pathological entity.

The disdain and demeaning behaviour shown by Indonesian governments towards Papuans in West Papua over the past 61 years are unforgivable and stained permanently in the soul of every living being in West Papua and New Guinea island.

“Right now, we are building Papua better,” declared Indonesia’s Vice-President, a narcissistic utterance from the highest office of the country, and this illustrates Jakarta’s complete disconnect from West Papua.

What led to this tragic situation?

West Papua has endured a lot for more than half a century, having been renamed and re-described numerous times by foreign invaders, from “IIha de papo” and “o’ Papuas” to “Isla de Oro”, or “Island of Gold”, to New Guinea, and New Guinea to Netherlands, English and German Papua and New Guinea. From this emerged Papua New Guinea, West Papua and Irian Jaya, and from Irian Jaya to Papua and West Papua.

As a result of renaming and colonial descriptions of Papuans as unintelligent pygmies, cannibals, and pagan savages; people without value, different foreign colonial intruders were able to enter West Papua and exploit and treat the Papuan people and their land, in accordance with the myth they created based on these names.

In addition to fostering a racist mindset, this depiction misrepresented reality as it was experienced and understood by Papuans over thousands of years.

The Jakarta settler colonial government continues to engage with West Papua with these profoundly misconstrued ideas. Hence the total disregard for what Papuans want or feel regarding their fate is a result of colonial renaming and accounts.

Now the eastern half remains under one name: Papua New Guinea. Jakarta’s settler colonial rulers just created five more settler provinces on the Western side of the island: South Papua Province, Central Papua Province, and Central Highlands Papua Province.

All these new settler colonial provinces are in the heart of New Guinea. Looking at West Papua’s history, we see so many marks and bruises of abuse and torture on her sacred body. In the future, West Papua is likely to suffer yet another grim fate of more torture with such dishonest words from Indonesia’s Vice-President.

Another sacred day

Today, December 1, marks yet another sacred day where we hold West Papua in our hearts and rally to her defence as her enemy marches to cut her into pieces on the settler colonial’s bed of Procrustes.

Let us remember and give glory to West Papua with the following words:

West Papua is an ancient and original particle, an atom of light and hope. It is a story about survival, resistance, betrayal, destruction, genocide, and survival against the odds. It is the last frontier where humanity’s greatness and wickedness are tested, where tragedy, aspiration, and hope are revealed. Papua is an innocent sacrificial lamb, a peace broker among the planet’s monsters, but no one knows her story — hidden deep beneath the earth – supporting sacred treaties between savages and warlords. West Papua is the home of the last original magic, the magic of nature. West Papua is the home of our original ancestors, the archaic Autochthons, the spiritual ancestors of our dream-time spiritual warriors — the pioneers of nature — the first voyageur across dangerous seas and land — the first agriculturalist — the most authentic, the original — we are the past and we are the future. West Papua is the original dream that has yet to be realised — a dream in the process of restoration to its original glory.

This is where West Papua is now. You cut me into pieces millions of times in millions of years, I will rebuild West Papua with these pieces a million times over again.

Happy West Papua Independence Day!

Yamin Kogoya is a West Papuan academic who has a Master of Applied Anthropology and Participatory Development from the Australian National University and who contributes to Asia Pacific Report. From the Lani tribe in the Papuan Highlands, he is currently living in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.