Fiji: Countdown to a coup

ANALYSIS: By David Robie in New Outlook

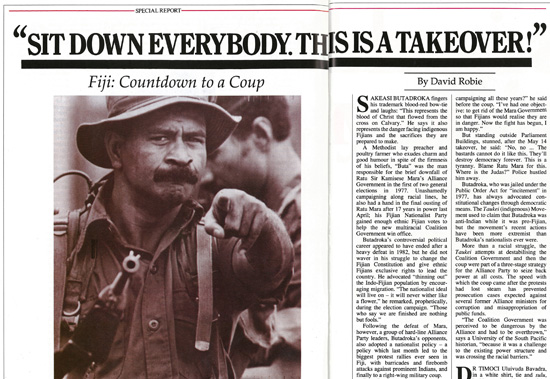

Sakeasi Butadroka fingers his trademark blood-red bow-tie and laughs: “This represents the blood of Christ that flowed from the cross on Cavalry.” He says it also represents the danger facing indigenous Fijians and the sacrifices they are prepared to make.

A Methodist lay preacher and poultry farmer who exudes charm and good humour in spite of the firmness of his beliefs, “Buta” was the man responsible for the brief downfall of Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara’s Alliance government in the first of two general elections in 1977. Unashamedly campaigning along racial lines, he also had a hand in the final ousting of Ratu Mara after 17 years in power in April 1987; his Fijian Nationalist Party gained enough ethnic Fijian votes to help the new multiracial Coalition government win office.

Butadroka’s controversial political career appeared to have ended after a heavy defeat in 1982, but he did not waiver in his struggle to change the Fiji Constitution and give ethnic Fijians exclusive rights to lead the country. He advocated “thinning out” the Indo-Fijian population by encouraging migration. “The nationalist ideal will live on — it will never wither like a flower,” he remarked, prophetically, during the election campaign. “Those who say we are finished are nothing but fools.”

Following the defeat of Mara, however, a group of hardline Alliance Party leaders, Butadroka’s opponents, also adopted a nationalist policy — a policy which last month led to the biggest protest rallies ever seen in Fiji, with barricades and firebomb attacks against prominent Indo-Fijians, and finally to a rightwing military coup.

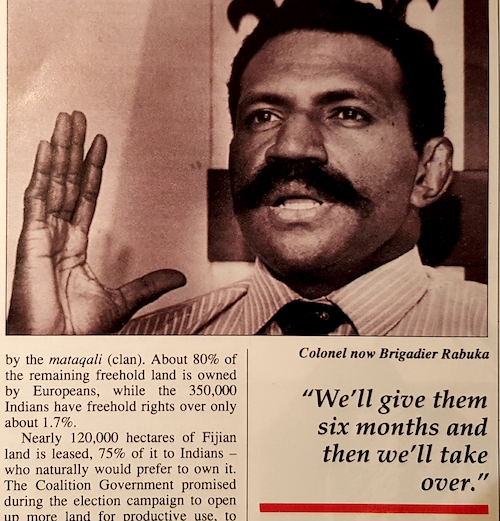

Does Butadroka regret lighting the racial fuse? No. At least, not until Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni “Steve” Rabuka — also a Methodist lay preacher — deposed the Coalition government and imposed martial law.

“Why do you think I’ve been campaigning all these years?” he said before the coup. “I’ve had one objective: to get rid of the Mara government so that Fijians would realise they are in danger. Now the fight has begun, I am happy.”

But standing outside Parliament Buildings, stunned, after the May 14 takeover, he said: “No, no . . . The bastards cannot do it like this. They’ll destroy democracy forever. This is a tyranny. Blame Ratu Mara for this. Where is the Judas?” Police hustled him away.

Butadroka, who was jailed under the Public Order Act for “incitement” in 1977, has always advocated constitutional changes through democratic means. The Taukei (indigenous) Movement used to claim that Butadroka was anti-Indian while it was pro-Fijian, but the movement’s recent actions have been more extremist than Butadroka’s nationalists ever were.

More than a racial struggle, the Taukei attempts at destabilising the Coalition government and then the coup were part of a three-stage strategy for the Alliance Party to seize back power at all costs. The speed with which the coup came after the protests had lost steam has prevented prosecution cases expected against several Alliance ministers for corruption and misappropriation of public funds.

“The Coalition government was perceived to be dangerous by the Alliance and had to be overthrown,” says a University of the South Pacific historian, “because it was a challenge to the existing power structure and was crossing the racial barriers.”

Constitutional storm

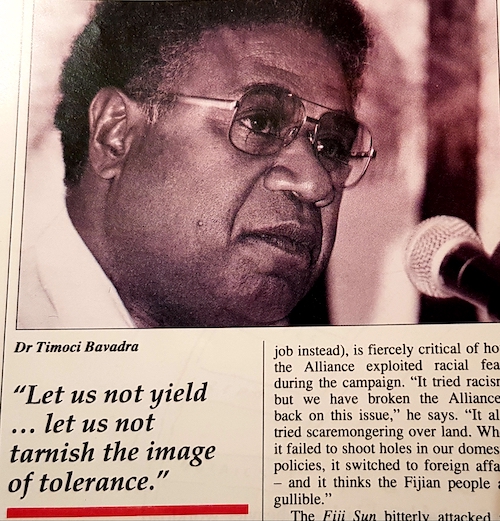

Dr Timoci Uluivuda Bavadra, in a white shirt, tie and sulu, had been relaxed in spite of the constitutional storm blowing around him — until he was put under house arrest. “Doc”, as the 52-year-old former civil servant is known to friends and party stalwarts, had slipped into the role of Prime Minister with ease and was approaching his task with the air of a physician with a kindly bedside manner.

Some now say too kindly. He was under pressure from several of his cabinet colleagues to take a hard line against the dissidents. But Dr Bavadra regarded reports of the extent of the opposition as exaggerated. Still, the day after the Lautoka firebombings he began to take harsher action. A day-long emergency meeting reviewed security.

Three days before the coup, key Taukei leader and former Works Minister Apisai Tora, widely regarded, like Colonel Rabuka, as a front man for the Alliance, was arrested by police and charged with “sedition and inciting racial antagonism”. Senator Jona Qio was also charged with arson over the Lautoka firebombings the day before the coup.

Prosecutions for corruption against other previous Alliance ministers were expected to follow.

Shortly before the coup, Dr Bavadra’s cabinet heard a report from the police special branch about the presence of two CIA agents in Fiji. Cabinet opinion was divided on whether the agents should be expelled.

Sources close to the Prime Minister said Rabuka was seen playing golf with the two men and Ratu Mara the Sunday before the coup, only a week after the United State Ambassador to the United Nations, General Vernon Walters, a former director of the CIA, visited Suva. Walters has been described by New Statesman magazine as “having been involved in overthrowing more governments than any other official serving the US government”. The diplomat had talks with Foreign Minister Krishna Datt and would have reported to Washington on his assessment of the minister and the government’s non-aligned policies.

Dr Bavadra, the sources said, also summoned the US ambassador to his office and complained that US aid funds had been used to help the Taukei Movement. The Australian-owned Emperor Gold Mines company was also accused of providing buses to help transport Fijian protesters to anti-government rallies.

Dr Bavadra had earnestly defended his government, saying it wqs “unthinkable” that he consider sacrificing the welfare of ethnic Fijians. He was saddened that dissidents suggested he would allow the government to put the welfare of Fijians at risk.

“We have been elected on a platform of improving the lives of all Fijians, not just one race and not just a ruling elite,” he said. “Lack of housing, poverty and poor wages should not be blamed on racial grounds.”

His government gained power on promises to improve social welfare, education, health and housing, and to eliminate corruption. But the way to do this, he argues, is through fairer distribution of the country’s wealth and better use of government resources. Dr Bavadra allocated the sensitive public service, Fijian affairs and home affairs portfolios to himself. Another Fijian, Mosese Volavola, became Lands Minister.

‘Let us not yield . . . let us not tarnish the image of tolerance.’

— Dr Timoci Bavadra

Dr Bavadra also pointed out that his government was elected by a five percent swing among ethnic Fijians away from the Alliance — mainly educated Fijians, particularly women, and young, underprivileged urban Fijians. Two nationalist candidates were declared bankrupt when counting began, but the Nationalist Party’s high polling split the Fijian vote in four crucial Suva electorates to boost the Coalition victory.

“Fiji needs this government to develop our maturity as a nation,” says Health and Social Welfare Minister Dr Satendra Nandan, 48, a poet and former literature lecturer at the University of the South Pacific. “It is vital for our peaceful future to show that a real multiracial government can run Fiji, we cannot keep brushing racial issues under the carpet.”

Dr Nandan, who had been tipped as likely Foreign Minister (Fiji Labour Party secretary-general Datt got the job instead), is fiercely critical of how the Alliance exploited racial fears during the campaign. “It tried racism, but we have broken the Alliance’s back on this issue,” he says. “It also tried scaremongering over land. When it failed to shoot holes in our domestic policies, it switched to foreign affairs — and it thinks the Fijian people are gullible.”

The Fiji Sun bitterly attacked the emotive smears used by the protesters, blaming them for worsening race relations. Rival Fiji Times, while conceding the Constitution was open for improvement, said it would “not be by brute force, threats or other illegal means”. (Both of Fiji’s daily newspapers are foreign-owned — the Sun by a New Zealand-Hong Kong owned company and the Times by Rupert Murdoch’s Herald and Weekly Times Ltd.)

Although several high chiefs condemned the protests, Ratu Mara’s failure to do so drew severe criticism and heightened suspicions about direct Alliance involvement, even though the party denied it.

When Ratu Mara surfaced as Foreign Minister in the military regime’s provisional government, it was widely believed that he was among the Alliance leaders who instigated the coup. Denials by Mara and Rabuka were unconvincing; the colonel needed the backing of the Alliance to stage the coup.

During at least one press conference, Colonel Rabuka was clearly being “coached” by the military regime’s Development Minister Peter Stinson and Information Minister Dr Ahmed Ali, both previous Alliance ministers concerned about the Coalition’s pledge to open the financial books.

Both of Mara’s former deputy prime ministers, Ratu David Toganivalu — regarded as the “Mr Clean” of the previous Alliance administration — and Mosese Qionibaravi, would have nothing to do with the military regime.

Among the Taukei leaders, besides Apisai Tora, is a rightwing trade unionist, Taniela “Big Dan” Veitata. A former member of the Fijian Nationalist Party, Veitata is regarded by many as a particular virulent racist.

“A new form of colonialism has been imposed on us, not from outside but from within our own country by those who arrived here with no rights and were given full rights by us — the taukei,” says Tora. But while Tora claims Dr Bavadra was a “puppet and a prisoner” of thw Indians, allegations are being made that Tora himself is a front for covert interference by the United States. When the new government took office, documents were found which purportedly linked Tora with American backing.

The “puppet” allegations against Dr Bavadra were based in his quick evelation of lawyer Jai Ram Reddy to the Senate and appointment as Attorney-General and Justice Minister. Reddy was an astute former opposition leader but he resigned from Parliament three years ago after a series of bitter clashes over what he considered to be the dictatorial style of Speaker Tomasi Vakatora. However, Reddy was the National Federation Party’s architect of the merger with the Fiji Labour Party and it was widely expected that he would be rewarded with a cabinet post.

Like Butadroka and Rabuka, Tora wants the Constitution to be amended so that only Fijians are elected to Parliament and to replace the Senate with an upper house based on the powerful, traditional Great Council of Chiefs, rather like Britain’s House of Lords. As Butadroka puts it: “We should follow Ghandi and Nehru in India: they told the British to get out of Parliament but have a free reign in business.”

Protected Fijian land rights

The so-called Indian problem began on 14 May 1979, when 489 Indians arrived as indentured labourers to work in the British-run sugar-cane fields. Just five years earlier, through a Deed of Cession — rather like the Treaty of Waitangi — signed by 13 high chiefs, the 320 islands which make up Fiji had become a British colony. One condition of the deed was that while property fairly acquired by European settlers at the time could be retained by them, Fijian rights to the rest of the fertile land should be protected.

These two events more than a century ago are at the heart of the present dispute. Descendants of those 489 Indians, joined by others over the following 37 years at the rate of about 2000 a year, now outnumber the indigenous Fijians, both within the 715,000 population and in Parliament. Forty-eight percent of the people are now Indo-Fijian, 46 percent Fijian (the higher birthrate means they will overtake Indians by 1990) and the rest “general”, or Europeans, Chinese and part-European. Nineteen of the Coalition’s 28 MPs are Indian.

In theory, Ratu Mara’s Alliance was a coalition of three parties: the Fijian Alliance, the Indian Alliance and the General Electors Association. After the Suva protests, however,two senior Indian Alliance officials quit and called on the other Indians to abandon the party.

Party general secretary Naresh Prasad said the protests had ruined the Alliance’s commitment to multiracialism and tolerance: “I get the feeling Fijians actually hate my guts yet they smile to keep my support.”

Britain’s departing colonial masters created a system of government which ensured each of the three major founding ethnic groups would be represented and any party or coalition forming the government would have substantial support from at least two of the three communities. Adapted from a Westminster-style democracy, the result is probably the world’s most complex electoral system. Each Fijian elector is represented by four members — two from that voter’s ethnic background and two which must not be from that community.

Parliament’s 52 seats are divided into two main categories and then into three sub-categories, making a total of six classes of seats — 25 national and 27 communal. Voters from all ethnic groups elect the national MPs while only specific ethnic communities elect communal MPs. The seats are broken down as: Fijian national 10, Indian national 10, general national 5, Fijian communal 12, Indian communal 12, general communal 3. To make the situation even more complicated, the six classes of seats overlap geographically.

Indigenous land 83 percent

Land distribution is fundamental to politics in Fiji. Under the Constituton, indigenous Fijians are guaranteed ownership of almost 83 percent of the land. Such Fijian land is inalienable and is owned collectively by the mataqali (clan). About 80 percent of the remaining freehold land is owned by Europeans, while the 350,000 Indians have freehold rights over only about 1.7 percent.

Nearly 120,000 hectares of Fijian land is leased, 75 percent of it to Indians — who naturally would prefer to own it. The Coalition government promised during the election campaign to open up more land for productive use, to “lease crown land to all citizens”.

But the government was also careful to stress that it recognised Fijian land ownership rights, and said no change would be considered “without the full consultation and approval of the Great Council of Chiefs. The Coalition is committed to uphold, protect and safeguard the ownership rights of people over their land and private assets as guaranteed under the Constitution and other laws of Fiji”.

The Alliance’s election campaign capitalised on Fijian fears over their land and tried to portray the Coalition as “communist” with a secret agenda designed to strip people pf their hand and hand it to the Indo-Fijians. Even if the allegations were without foundation, they have struck a responsive chord with some Fijians. “It is neocolonialism by Indians,” says “Big Dan” Veitata. “Unless we stop it now, we will be no better off than the kanaks in New Caledonia, the Australian Aborigines and the New Zealand Māori.”

There are many prosperous gujerati (Indian businessmen), but Fijian business is still dominated by foreign — mainly Australian, New Zealand and local European — ownership. And many of the poorest people in Fiji are Indian squatters or jobless.

However, the Indian community dominates the sugar-growing industry which is the mainstay of the Fijian economy. Nearly all the crop produced by Indians is grown on land leased from native landlords on the basis of limited tenure.

Ideally, the Indian community would like to have increased land rights, or, failing that, a greater security of tenure on leased land. Fijians, however, stubbornly stick to the traditional system of land distribution, the basis of their hold on power.

‘We’ll give them six months and then we’ll take over.’

— Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka

In the late 1950s, there were barely 130 children of Fijian-Indian marriages. Since then the segregation of the races practised by the colonial administration through legal decrees has largely disappeared. Mixed marriages are now more common and mixed-race children more numerous than a generation ago. Figures are difficult to establish because children in Fijian-Indian marriages and relationships are not regarded as a separate category.

The colonial administration segregated living areas for the different racial groups. For example, in Suva, Vatuwaqa, Samabula and the Signal Station were reserved for Indians while areas like Toorak, the Domain and Tamavua Heights were for white settlement. Draiba was for Indian civil servants. This was coupled with a policy that non-indigenous races were barred from living in Fijian villages.

“The British practised a form of dictatorship from 1875 to 1963,” says Dr Vijay Naidu, a University of the South Pacific sociologist. “From 1904, whites had representation in the legislature and Indians were represented by nomination in 2016 and by election in 1929. The governor and the official members could veto any resolutions of the elected representatives. Indigenous Fijians voted for the first time in 1963. This was not all, “democracy” as practised in Fiji meant that Europeans, though numerically a minority, had parity with the other ethnic categories.”

According to Dr Naidu, the friction between Fijian and Indo-Fijian is highly exaggerated: “For black labour in Fiji, the owners and managers of transnational corporations, who are largely white, constitute the main antagonists.” He also says that the general electors (voters who are neither Fijian or Indian) have traditionally been the most racial in their voting, something hardly remarked on by foreign or even local journalists.

However, in spite of his comments, Dr Naidu found himself on the military regime’s “hit list” of about 30 people regarded as founders or sympathisers of the Labour Party. He went into hiding when police arrested two people wrongly identified as him.

“Fijians opposing the Coalition are led by those who have lost their privileges by being ousted — it is political rather than racial,” says Dr Tupeni Baba, a flamboyant university lecturer who became Education Minister. “The Alliance wanted a less open government than ours, judging from its failed attempts to prosecute people who delved into its actions and from the way it shielded itself from the media. It suffers from a fortress complex.”

Timeline of a coup

Saturday, April 11, 1987: A tropical beeze tugs at the coconut palms along the waterfront of the capital, Suva. Week-long polling in Fiji’s fifth general election since independence has just ended and there is excitement in the air. Supporters of the Fiji Labour Party-led Coalition with the Indian-led National Federation Party sense victory.

At Ratu Mara’s official residence in Veuito there is anger and disbelief. “These people cannot govern,” say several Alliance leaders. “We’ll give them six months and then we’ll take over.” Already Alliance activists meeting in the urban ghetto of Raiwaqa have begun plotting how to destabilise the future government.

Sunday, April 12: Labour’s Dr Timoci Bavadra, a man who had never sat in Parliament, claims victory before the final figures: 28 seats to 24. After an address to the nation on Radio Fiji that night, Dr Bavadra shares a bowl of yaqona with well-wishers, including New Zealand High Commisionetr Rod Gates at the modest clapboard headquarters of the Fiji Labour Party.

Monday, April 13: Dr Bavadra is sworn in as Prime Minister and meets, one by one, the chairman of the Public Service Commission, the commissioner of police and the commander of the Royal Fiji Military Forces. (In 1977, when the Indian opposition won the first election but were unable to form a government, none of these crucial services would cooperate with it.) Doubt still remains about the Fijian-dominated military.

In his first pres conference as Prime Minister, Dr Bavadra pledges to introduce a New Zealand-style ban on nuclear warships and attacks the Australian and United States claims of Libyan and Soviet threats in the region, saying he cannot see any evidence. He confirms Fiji will follow an “active non-aligned” foreign policy.

Tuesday, April 14: Honouring his pledge of a racially “balanced” government, Dr Bavadra reduces the cabinet from 17 to 14 members and names seven Indo-Fijians, six Fijians and one minister representing “general electors” (European or mixed race).The previous Alliance government was dominated by indigenous Fijians.

Dr Bavadra flies to the chiefly island of Bali to pay his respects to the former Governor-General, Ratu Sir George Cakobau, a paramount chief. When he became Labour Party leader two years ago, Dr Bavadra had visited Cakobau to seek his support in trying to win over the Fijian villages, the traditional stronghold of the Alliance Party.

Easter: Angry Fijian villagers set up barricades near the the northern town of Tavua on the main island of Viti Levu, demanding the Coalition government be ousted. A meeting of 3000 Fijians in Viseisei, Dr Bavadra’s home village in western Viti Levu, protests against the government.

Apisai Tora, a former Lands Minister in the Alliance government, accuses the new administration of “dispossessing Fijians in their own country”. He attacks the assigning of key commerce, finance, foreign affairs and justice portfolios to Indo-Fijians. The meeting votes to freeze land leases to non-Fijians.

Dr Bavadra, who is accused of being a puppet of the Indians, condemns illegal protests and “any attempts to destabilise Fijian society”. But the government remains cautious, anxious to avoid racial strife.

Friday, April 24: Between 5000 and 8000 Fijians state a peaceful anti-government protest rally in Suva, the biggest demonstration in Fijian history. Racist slogans include “Fiji fr the Fijians”, “Stop this Indian government”, “Fiji now little India — say no!” and “Out with foreign puppets”. Protest leaders petition the Governor-General, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, with a demand that the Constitution be changed to guarantee Fijian control in the country.

Dr Bavadra warns Fijians in na national radio broadcast not to allow a “disgruntled few” to sabotage the country. “Let us not yield . . . let us not tarnish the image of tolerance and goodwill for which Fiji is renowned,” he says. “Where is the justice and reason in trying to destabilise and remove a government as soon as it has been elected?”

Sunday, May 3: Police and military forces are put on alert after a Molotov cocktail explodes in the law offices of Justice Minister Jai Ram Reddy in the western city of Lautoka. Four nearby Indian businesses are firebombed at the same time. Shortly after the fires, police detain Senator Jina Qio, one of the Suva protest organisers, and release him after four hours of questioning. (He is later charged.)

Friday, May 8: Anti-government organisers claim at least 30,000 Fijians will blockade the opening of Parliament. However, the government refuses to grant a permit for a legal protest and only about 1000 people picket the opposition Alliance lobby rooms. But that is enough to prevent all but five Alliance MPs being sworn in. A rebel Alliance MP, Militoni Leweniqala, is elected by the House as Speaker and he is immediately banned from the Alliance caucus. More destabilisation threats are made but the Bavadra government appears to be weathering the storm.

Thursday, May 14: Ten soldiers wearing gasmasks and armed with pistols burst into the parliamentary chamber. Sitting in the public gallery, Lieutenant-Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka rises, moves toward Dr Bavadra and orders: “Sit down everybody. This is a takeover!”

The soldiers abduct Dr Bavadra and 26 of his MPs at gunpoint, herding them into military trucks to take them to detention. Heads of the military and police forces are deposed, the Constitution suspended and the colonel forms a provisional council of ministers.

The Governor-General, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, declares a state of emergency and refuses to recognise the military regime as Australia, Britain and New Zealand exert pressure for a return to constitutional democracy.

Tuesday, May 19: After five days of intense pressure from Colonel Rabuka for the vice-regal seal on his military regime, Ganilau still refuses to endorse the junta. He orders the dissolution of Parliament and return to barracks for Rabuka’s soldiers, and he calls for a new election.

David Robie was one of only two New Zealand journalists to cover the fateful 1987 election in Fiji and he correctly predicted the election of the Fijian Labour Party-led coalition to power. He also covered the post-coup period and later, as head of journalism at the University of the South Pacific, led a group of student journalists in their award-winning coverage of the May 2000 George Speight coup. His early Fiji coup coverage was summarised in his 1989 book Blood on their Banner: Nationalist Struggles in the South Pacific and his Speight coup coverage was included in a 2014 sequel, Don’t Spoil My Beautiful Face: Media, Mayhem and Human Rights in the Pacific. This article was published in the June/July 1987 edition of New Outlook magazine, pp. 22-29.