INTRODUCTION: By Mark Derby

Just weeks after Owen Wilkes’ sudden death in 2005, a van arrived at his basic bach in Kāwhia to carry away his lifetime’s collection of research materials. By the time the bach had been emptied of the carefully catalogued and labelled file-boxes and folders that lined every wall, the van was fully loaded.

The collection was taken to the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, New Zealand’s largest manuscript repository, where it remains publicly accessible as a uniquely valuable resource for later generations of researchers.

Still more of Owen’s findings and analysis are held in other collections — at Canterbury and Auckland University libraries, and elsewhere. This exceptional public legacy of hard-copy information has been extensively drawn upon by several of the contributors to the book Peacemonger: Owen Wilkes: International Peace Researcher, who have, nevertheless, only touched on its extraordinary breadth and multifariousness.

- READ MORE: Owen Wilkes: Exposing foreign militarism on the ‘backside of the earth’

- Other Owen Wilkes articles on Café Pacific

Lifelong love for archaeology

Owen Wilkes was born in the Christchurch suburb of Beckenham in 1940. His parents ran a corner dairy (which still operates from the same site beside the Heathcote River) and later a Kilmore Street guesthouse. He went to Beckenham Primary School and then Christchurch West High School (now Hagley College) from 1954–58.

Owen was never a keen student but he displayed a capacity for hard work, an intellectual interest in field sciences and a love for the outdoors, particularly the chance to tramp in the backcountry. During one school holidays he worked in an abandoned goldmine in the Lake Brunner area. No gold was recovered but the experience began a long interest in the West Coast.

He generally made the long and demanding journey from Christchurch to the Coast by pushbike to ensure that he had transport when he arrived.

Intermittently between 1959 and 1966 Owen studied science subjects at the University of Canterbury, majoring in geology. He passed five units of the requisite eight for a BSc, but did not complete his degree and never regretted his lack of academic qualifications.

While at university he discovered a lifelong love for archaeology and even as an undergraduate student he made respected contributions to fieldwork, initially in the South Island.

Owen’s substantial, albeit somewhat informal and episodic, career as an archaeologist is described in this book by Neville Ritchie.

In the summer of 1962 an opportunity arose to carry out fieldwork as an entomologist in Antarctica, for a project supported by and indirectly benefitting the US Navy. Owen threw himself into the work with his usual energy, relishing the physical challenges of a snowbound environment that somewhat resembled the South Island high country, and at that time untroubled by his project’s military and political undertones.

Further archaeological work in the Cook Islands was followed by another entomological research expedition, this time to the subantarctic Kermadec Islands. The expedition, he discovered, was part of a US military germ warfare research project. Subsequent expeditions in the Pacific were also sponsored by US government and military agencies, and Owen began to realise and question the role of the military in scientific research.

When he was given the chance to return to the US McMurdo base in Antarctica, he did so with the deliberate but covert intention of applying his formidable research skills to exposing the military use of nuclear power there. The outcome of that exercise is described in this book by Dr LRB Mann.

By 1968 Owen had decisively committed to researching and exposing the offshore facilities of the US war machine in his own country, elsewhere in the Pacific, and further afield. Supporting himself, his family and often his friends through a succession of low-paid jobs, he relentlessly absorbed official documents from publicly accessible sources, read between the lines to understand the unstated and covert information that the documents revealed, and then disseminated his findings at almost every possible level, from self-published pamphlets to learned papers in academic journals.

In the course of several decades, mainly preceding the era of the personal computer, he assembled an extraordinary body of documents, all carefully cross-referenced and freely shared with fellow researchers worldwide. In this book Nicky Hager describes Owen’s self-taught, unorthodox and remarkably efficient researching system, and its continuing value for addressing major political issues of the present day.

Although invariably non-violent, politically non-aligned and generally law-abiding, Owen encountered official opposition, harassment and intimidation in various forms as he became internationally known for the quality and impact of his peace research.

Diane Hooper describes the actions taken by the Buller County Council towards Owen’s self-built and structurally advanced eco-house, while he was working in Norway at the invitation of its renowned peace research institute.

Foreign military installations

Both in Norway and Sweden, Owen helped to reveal the presence and purpose of foreign military installations, some of them part of a worldwide network of nuclear weapon command and control systems. His Scandinavian colleagues Dr Ingvar Botnen and Dr Nils Petter Gleditisch describe his activities on the opposite side of the world from New Zealand, where he revelled in its natural wonders, yet eventually risked a lengthy prison sentence on charges of violating national security.

Owen spent much of his adult life under surveillance by intelligence services, and Maire Leadbeater reveals what is known to date of those services’ frequently inaccurate and unproductive findings.

Although a thorn in the side of governments of all shades, in time their officials were obliged to acknowledge the accuracy and importance of Owen’s work. In 1988 he became one of about 3000 New Zealanders to receive the NZ Commemoration Medal, a one-off decoration issued “in recognition of the contribution they have made to some aspect of New Zealand life”, in his case for services to peace and disarmament.

Owen’s adult life was lived periodically in rural, remote localities, growing much of his own food and regularly making long and physically challenging treks into the surrounding wilderness. He clearly preferred this simple, outdoor way of life to any other, yet he repeatedly abandoned it and returned to urban centres in order to apply his skills at research and writing more effectively, a pattern of residence that demonstrates a remarkable generosity of spirit.

Owen came to hold unchallenged authority within the peace and disarmament movement in Aotearoa and more widely, while remaining unassuming, accessible and collaborative in his working habits. As Dr David Robie, Ken Ross, Murray Horton and other contributors to Peacemonger make clear, he can be accorded a large measure of credit for his country’s nuclear-free status, for the nuclear-free Pacific movement, and for exposing covert military activity worldwide.

Craggy, fit, fiercely intelligent

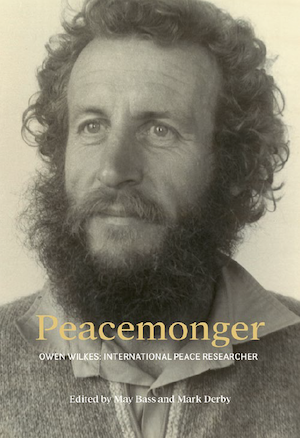

I first met Owen Wilkes in 1975, on the South Island Resistance Ride. He was already a near-legendary figure — craggy, fit, fiercely intelligent, highly independent in thought and action. He became a major inspiration to me, along with many other young people eager to understand the various powerful forces we recognised as dominating our lives and directing our futures.

Owen and I collaborated occasionally afterwards, lastly in the 1990s for a TV news item about New Zealand’s WW2 chemical warfare stocks. The story was prompted by the release of Owen’s paper on the history of chemical weapon use in New Zealand, and especially by his revelation that in 1946 the Defence Department decided to dump obsolete cannisters of its chemical toxins in a deep offshore trench in Cook Strait. (Owen incurred the wrath of friends in the environmental movement for expressing the view that this was a reasonably safe and appropriate way to dispose of such dangerous waste — he was always prepared to advance an unpopular position if he believed that the science supported it.)

I asked him to come down to Wellington from his home in Kāwhia to front the news story, and he agreed without hesitation. Although he was a respected contributor to academic journals, Owen was equally willing to share his knowledge through mass media and less conventional channels, including publications aimed at young people.

He turned up in the capital on schedule, dressed in his customary outfit of baggy jersey and shorts, unencumbered with luggage but with all the facts at his command. He then gave a series of wry, relaxed and authoritative interviews to camera in front of the disused weapons bunkers on the Belmont hills above Wellington harbour.

The producer was delighted, and offered to thank his rangy interviewee by buying him a meal at any establishment of his choosing. It was a sunny day and Owen opted for fish and chips in Parliament grounds.

Sprawled comfortably in a shady spot on the grass, he remained continuously alert and pointed out something happening nearby that I hadn’t noticed. Parliamentary security staff were checking underneath all incoming vehicles with a large, wheeled mirror. Owen was fascinated. He had not seen this particular equipment in use before, and filed the observation away for future reference while speculating idly about the reasons for the heightened security.

I’ve never met anyone who made less distinction between their work and leisure. As this book explains, Owen could take a holiday on a remote west coast beach and discover a covert government communications facility. Or face espionage charges from the Swedish government after taking photographs from the roadside during a cycle tour.

The entire world kept revealing itself to him in ways both marvellous and outraging. It simply called for close and patient observation, followed by scrupulous analysis, and then dissemination of the findings. I learned a great deal from Owen’s uniquely critical engagement with his surroundings, and I continue to benefit from his example in my own work.

The contributors to this book are themselves leading figures in their respective fields, who all knew and worked closely with Owen. The editors hope that these collective memories and accounts will provide a lasting record of a uniquely impressive character, and also inspire others to confront the universal evils of militarism, imperialism, social injustice and environmental destruction. Owen was an admirable and unforgettable New Zealander — unpretentious, fearless, indefatigable, at times insufferable. All of us who contributed to this book consider ourselves lucky to have known him, and we hope in this way to sustain and extend his influence and example.

- Published originally as the Introduction in May Bass and Mark Derby (eds.), Peacemonger: Owen Wilkes: International Peace Researcher, Raekaihau Press, Wellington, 2022. ISBN 9781991153869. Republished with the permission of co-editor Mark Derby.