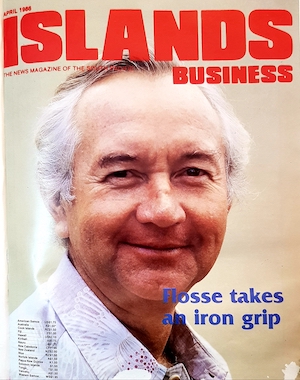

Victory was complete. Gaston Flosse crushed all opposition at the polls. David Robie in Pape’ete asks how powerful can he become as France’s newly created Pacific Affairs boss?

By David Robie in Islands Business

Some brand him as the Pacific’s “Papa Doc”; others regard him as the man with a vision which will turn Tahiti into the economic and cultural showpiece of the region.

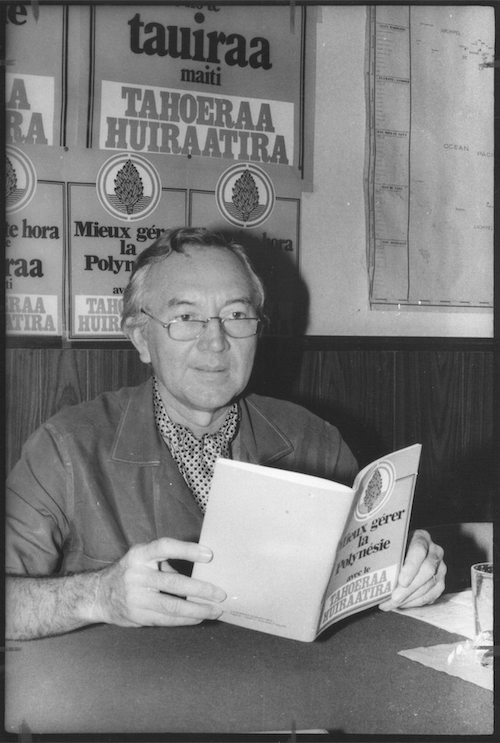

For two decades Gaston Flosse has been the mayor of the affluent Pape’ete suburb of Pirae. Ten years ago he was President [Speaker] of the Tahitian Territorial Assembly. But the real start of his phenomenal rise to power was four years ago [1982] when his neo-Gaullist party, Tahoeraa Huira’atira, wrestled control from the jaded autonomist Front Uni coalition of Francis Sanford.

Since then, the 54-year-old businessman has consolidated his power in such a devastating way that opponents are bitterly talking of “another dictatorship” or one-party rule.

Two years ago [1984] he assumed the title of President of “French” Polynesia with the authority of a prime minister under a statute reform which granted the territory considerable self-government powers. And barely three days after crushing defeat of the fragmented Tahitian opposition parties at the polls in March he was named by incoming French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac to the newly-created post of State Secretary for Pacific Affairs.

It was a triumph for his platform of internal autonomy for Tahiti and a greater say in French Pacific policy by islanders. Already he is being touted as the powerbroker of the region.

Delighted, Flosse praised Chirac for keeping his pledge. “I’ve already told him,” he added, “that I would only accept the job providing he gave me the support necessary to apply the policies of France in the Pacific.”

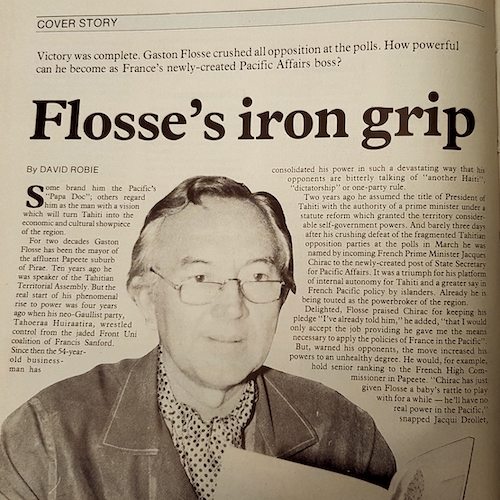

But, warned his opponents, the move increased his powers to an unhealthy degree. He would, for example, hold senior ranking to the French High Commissioner in Pape’ete. “Chirac has given Flosse a baby’s rattle to play with for a while — he’ll have no real power in thePacific,” snapped Jacques Drollet, leader of the pro-independence socialist party Ia Mana Te Nunaa (Power to the People). “And, in any case, the Chirac government won’t last a year.”

Personality attacks against Flosse have been the most savage ever seen in a Tahitian election campaign. Although his policies have clearly meant a giant economic leap forward, his critics claim only supporters of the party have cashed in. Even when Flosse turned the tables on his opponents on polling day, 16 March 1986, by becoming the first Tahitian leader in 30 years to win an outright majority in an election, the nasty barbs continued.

Tahoeraa Huira’atira, which won power through a coalition in 1982, retained office with 21 seats, a majority of one in the expanded 41-seat Territoral Assembly. (The number later rose to 22 when an electoral office gave Tahoeraa another seat.) The vote also gave the indépendantistes a surprise success.

But, alleged Flosse’s opponents, Tahoeraa achieved its win by “buying” votes with favours and gifts of building materials for islanders on many of the 120 small outlyng islands and atolls in Polynesia. The opponents also claimed that an electoral reform had gerrymandered the remote islands, which cover an area of the Pacific almost as large as Australia, to Tohoeraa’s advantage.

“it is an outrage that Tahoeraa should win a majority in the Assembly with a minority of the votes,” said Quito Braun-Ortega, one of the leaders of the opposition coalition Amuitahiraa No Polinesia. “We cannot accept this result.” On the windward islands of Tahiti and Moorea, where two-thirds of French Polynesia’s 160,000 population live, Tahoeraa won just over a third of the vote. Yet this was still enough to gain nine seats out of the 22 at stake. Overall, Tahoeraa won 40 percent of the 74,000 votes cast. (A record 105,000 voters were registered.)

‘Unjust and scandalous’

By the end of the week, Ortega’s accusations had become increasingly bitter. He declared the “real majority” would resist Flosse’s government and said he electoral law was “unjust and scandalous”. Pape’ete mayor Jean Juventin, leader of another key opposition party, Here Ai’a, added: “A real fight is starting.”

The seven opposition parties held a series of meetings to consider a strategy for seeking an annulment of the results, particularly in the Tuamotus, where Tahoeraa won four crucial seats.

Ortega accused Tahoeraa of using state funds and the territorial institutions for the benefit of its electoral campaign. There was also talk of occupying the Territorial Assembly building in protest so that the new Parliament could not convene on 27 March 1986.

With Flosse and Vice-President Alexandre Leontieff away in Paris to meet Chirac, Tahiti’s Minister of Internal Affairs, Patrick Peaucellier, called a press conference in whivh he accused Amuitahiraa of using “seditious language” in challenging the election results. Defending the electoral law, he said: “Tahiti isn’t a banana republic where coups d’etat can take place any old time.”

It was a grave situation when the opposition could talk about taking to the streets. Peaucellier said the opposition lacked political maturity. he warned the government would not tolerate any attempted occupation of the Territorial Assembly, as happened in 1976 when Front Uni assemblymen were agitating against Paris for reforms.

“If it doesn’t have anything to hide,” added Drollet, “Tahoeraa should be happy to have the inquiry. If it opposes it then our suspicions are confirmed. But I maintain there has been massive corruption.”

Criticism on a similar theme pas persisted over the last few months. One Paris newspaper, Libération, published a full-page article in January citing the alleged corruption. Flosse responded by filing a defamation suit against the newspaper. An issue of the party paper, Te Tahoeraa, also denied the allegations in a report headed: “Monsieur 10 percent doesn’t exist.” It also quoted Drollet telling Agence France-Presse: “None of the accusations against Flosse have to this day been substantiated. Nobody has been able to prove anything.”

The electoral allegations have centred on two government agencies, the US$10 million Islands Aid Fund (FEI) set up in 1984 to help develop the outer islands, and the Territorial Reconstruction Agency (ATR), established after the tropical cyclone devastation in 1983. ATR has built more than 1000 homes for the homeless.

However, the opposition claims that some houses or building materials have benefited party supporters while many Tahitian homeless remain without a place. Fei is also the Tuamotu word for a species of red banana used as the party symbol for Tahoeraa. So, in the minds of many islanders development work done by FEI was immediately associated with personal assistance from Flosse’s party.

The opposition claimed the government abused its powers by using both FEI and ATR to further its electoral prospects. Ortega also accused the French administration of being at least “ambivalent” over the election and having contributed to the alleged fraud.

Flosse rejected the allegations, saying: “They’re absolutely false.” He denounced the local newspapers and television station for “encouraging” the attacks. he also pointed out that the electoral law had been in use for several years. “You know very well there hasn’t been any fraud,” he told La Dêpeche. “The best proof is at Pirae, where the magistrate was preset and in charge of scrutineering. The same at Pape’ete, at Faa’a .. .in all the big centres a magistrate was present. It’s the opposition which was carrying out a fraud.”

But the electoral figures, as cited by Ortega, were hard to ignore. “Nobody had time to seriously study the implications of the new electoral law,” said Ortega. “But what it means is that a voter from the remote Austral or Tuamotu islands is equal to three voters from Tahiti. What sort of democracy is this?” In effect, it took about 2400 votes to win a seat on Tahiti and only about 800 votes on outer islands.

The opposition won 63 percent of the votes in the Windward Islands (Tahiti and Moorea) against Tahoeraa’s 37 percent; more than 54 percent on the Leeward Islands, against Flosse’s less than 46 percent; more than 54 percent in the Tuamotus (against 45.5 percent) and more than 57 percent in the Australs (against nearly 43 percent). It was only in the Marquesas where Tahoeraa actually won a majority of votes (more than 66 percent against 34 percent for the opposition).

Power on a minority

In the most “scandalous” case, Tahoeraa won four out of five seats in the Tuamotus with 45 percent of the vote. The other seat was won by Tapuro Napo, the one-man band party of Napoleon Spitz, who later announced he would support Tahoera’a. The Tuamotus were the islands that benefited most from FEI’s development assistance.

“We cannot confer power on a minority which has so far clearly been rejected by most Tahitians,” said Ortega. “Or the Tahitian people are in danger of revolting like in the Philippines. We hope the state will have the wisdom to realise this.” But there seemed little hope of a “grand coalition” of opposition parties as Ortega hoped — the political differences were too great. “This idea is moe moea — a big dream,” scoffed Drollet.

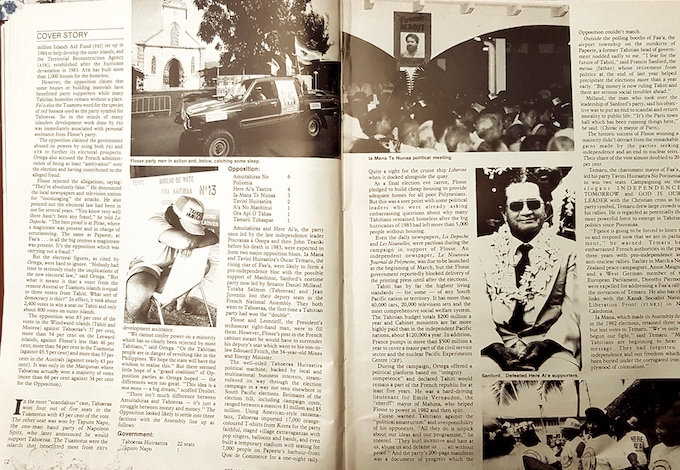

“There isn’t much difference between Amuitahiraa and Tahoeraa — it’s just a struggle between money and money.” The opposition looked likely to settle into three factions with the Assembly line-up as follows:

Government

- Tahoeraa Huira’atira 22 seats

- Tapuro Napo 1

Opposition

- Amuitahiraa No Polinesia 6

- Here Ai’a Taatira 4

- Ia Mana Te Nunaa 3

- Tavini Huira’atira 2

- A’a No Maohinui 1

- Ora Api O Tahaa 1

- Tamarii Tuhaapae 1

Amuitahiraa and Here Ai’a, the party once led by the late independence leader Pouvanaa a Oopa and then John Teariki before his death in 1983, were expected to form two major opposition blocs. Ia Mana and Tavini Huira’atira’s Oscar Temaru, the rising star of Faa’a, were likely to form a pro-independence bloc with the possible support of Maohinui, Sanford’s onetime party now led by Senator Daniel Millaud. Tutuha Salmon (Tahoeraa) and Jean Juvenin lost their deputy seats in the French National Assembly. They both went to Tahoeraa, the first time a Tahitian party had won the “double”.

Flosse and Leontieff, the President’s technocrat right-hand man, were to have filled the seats. However, Flosse’s post in the French cabinet meant he would have to surrender his deputy’s seat which went to his son-in-law Édouard Fritch, the 34-year-old Mines and Energy Minister.

Well-oiled political machine

The well-oiled Tahoeraa Huira’atira political machine, backed by local and multinational business interests, steamrollered its way through the election campaign in a way not seen elsewhere in South Pacific elections. Estimates of the election bill, including campaugn costs, ranged between a massive $1 million and $5 million. Using American-style razzamatazz, Tahoeraa imported 17,000 orange-coloured T-shirts from Korea for the party faithful, staged village extravaganzas with pop singers, balloons and bands, and even built a temporary stadium with seating for 7000 people on Pape’ete’s harbour-front Quai de Commerce for a one-night rally.

Quite a sight for the cruise ship Liberte when it docked alongside the quay.

As a final election eve carrot, Flosse pledged to build cheap housing to provide adequate homes for all poor Polynesians. But this was a sore point with some political leaders who were already asking embarrassing questions about why many Tahitians remained homeless after the big cyclones of 1983 had left more than 5000 people without housing.

Even the daily newspapers, La Dépêche de Tahiti and Les Nouvelles, were partisan during the campaign in support of Flosse. An independent newspaper, La Nouveau Journal de Polynésie, was due to be launched at the beginning of March, but the Flosse government reportedly blocked delivery of the printing press until after the elections.

Tahiti has by far the highest living standards — for some — of any South Pacific nation or territory. It has more than 40,000 cars, 20,000 television sets and the most comprehensive socil welfare system. The Tahiti budget totals $200 million a year to cover a major part of the civil service sector and the nuclear Pacific Experiments Centre (CEP).

During the campaign, Ortega offered a political platform based on “integrity . . . competence” and declared Tahiti would remain part of the French republic for at least five years. He was a hard-driving lieutenant for Emile Vernaudon, the “sheriff” mayor of Mahina, who helped Flosse to power in 1982 and then split.

Flosse warned Tahitians against the “political amateurism” and “irresponsiblity” of his opponents. “All they do is nitpick about our ideas and our programme,” he sneered. “They hurl invective and hate at us, abuse us and defame us . . . all without proof.” And the party’s 200-page manifesto was a document of progress which the opposition could not match.

Outside the polling booths of Faa’a, the airport township on the outskirts of Pape’ete, a former Tahitian head of government nodded sadly to me. “I fear for the future of Tahiti,” said Francis Sanford, the metua (father figure) whose retirement from politics at the end of last year [1985] helped precipitate the elections more than a year early. “Big money is now ruling Tahiti and there are serious social troubles ahead.”

Independence parties make gains

The historic success of Flosse winning a majority did not detract from the remarkable gains made by the parties seeking independence and an end to nuclear tests. Their combined share of the vote almost doubled to 20 percent.

Temaru, the charismatic mayor of Faa’a, led his party Tavini Huira’atira to win two seats. Campaigning on the slogans “Independence Tomorrow” and “God is our Leader” with the Christian cross as the party symbol, Temaru drew large crowds to his rallies. He is regarded as potentially the most powerful force to emerge in Tahitian politics since Pouvanaa.

“France is going to be forced to listen to us and respond now that we are in Parliament,” he warned. Temaru has embarrassed French authorities in the past three years with pro-independence and anti-nuclear rallies. Earlier in March a New Zealand peace campaigner, Annie Maignot, and a West German member of the European Parliament, Dorothy Piermont, were expelled for addressing a Faa’a rally at the invitation of Temaru.

He also has close links with the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS) in New Caledonia.

Ia Mana, which made its Assembly debut in the 1982 elections, retained three seats but lost votes to Temaru. “We’ve only just begun our fight,” said Temaru. “Many Tahitians are beginning to hear our message. They had forgotten our independence and our freedom which has been buried under the corrugated iron and plywood of colonialism.”

- In 2022, French Polynesia’s 91-year-old former president and veteran politician, Gaston Flosse, was given a suspended prison sentence for producing a fake contract to register as a Pape’ete voter. The criminal court gave him a nine-month suspended sentence, an US$,000 fine, and declared him ineligible for public office for five years, dashing his hopes of standing in the 2023 territorial elections.

This is part 1 of six reports in David Robie’s nine-page cover story portfolio for Islands Business magazine covering the 1986 Tahitian elections. Oscar Temaru went on to become President of French Polynesia five times, the first instance in 2004. His party made a comeback in 2023 to decisively win the Territorial Assembly outright, with Moetai Brotherson as President and independence still the longterm goal.